The Penal Code in the Joseon Dynasty: Harsh Punishments

Corporal punishment administered during the Joseon Dynasty was severe and of five basic types: whipping, flogging, hard labor, banishment, and death (see Gwangju News, December 2019, pp. 20–21). In this companion article, originally appearing in the December 2007 issue of the Gwangju News, Prof. Shin Sang-soon (1922–2011) describes an array of additional punishments that could be labeled torturous, mortifying, and just plain bizarre. — Ed.

Joseon society could be characterized as a Confucian, centralized, bureaucratic, and feudal society. Confucianism was the national creed providing guiding principles for government, society, and education. All systems and policies established during the Joseon period (1392–1910) could be regarded as being influenced by the tenets of Confucianism. Styles of penal administration were in part carry-overs from the preceding Koryo era (918–1392) but were reinforced with Confucian ethics. The Joseon criminal code provided compassion clauses to safeguard the offenders’ human rights, and kings often attached much importance to compassionate administration of penal laws as a symbol of royal benevolence. This explains the frequent abolishment of certain punishments by royal decrees as unlawful and inhuman.

In addition to the basic punishments (whipping, flogging, hard labor, banishment, and death), further penalties included tattooing, confiscation of one’s slaves, confiscation of one’s property, compensation levied for damages, and guilt by association, by which family, relatives, and associates could also be punished for the perpetrator’s crime.

Applied mainly to thieves who were sentenced to flogging, hard labor, and banishment, tattoos originally went on the criminal’s wrist or mid-forearm. The size of the tattooed Chinese character for “thief” was about 4.5 square centimeters, with strokes of the character being five millimeters in width. The purpose was to inflict a sense of shame into these lawbreakers by permanently branding them as convicted criminals and to control them by making them known to the public. However, since a tattoo on the arm or wrist could easily be concealed under a sleeve, thus diminishing the intended results, the placement of the tattoo was later changed to the face. The facial tattoo was devised to prevent thievery during severe famines, and was thus only seldom applied. In any case, the facial tattoo was a severe punishment and forced the bearer to spend the rest of their life with the stigma of being a convicted criminal. Tattooing was abolished in the 16th year of the reign of King Yeongjo (1740), when he destroyed all tattooing tools by royal decree.

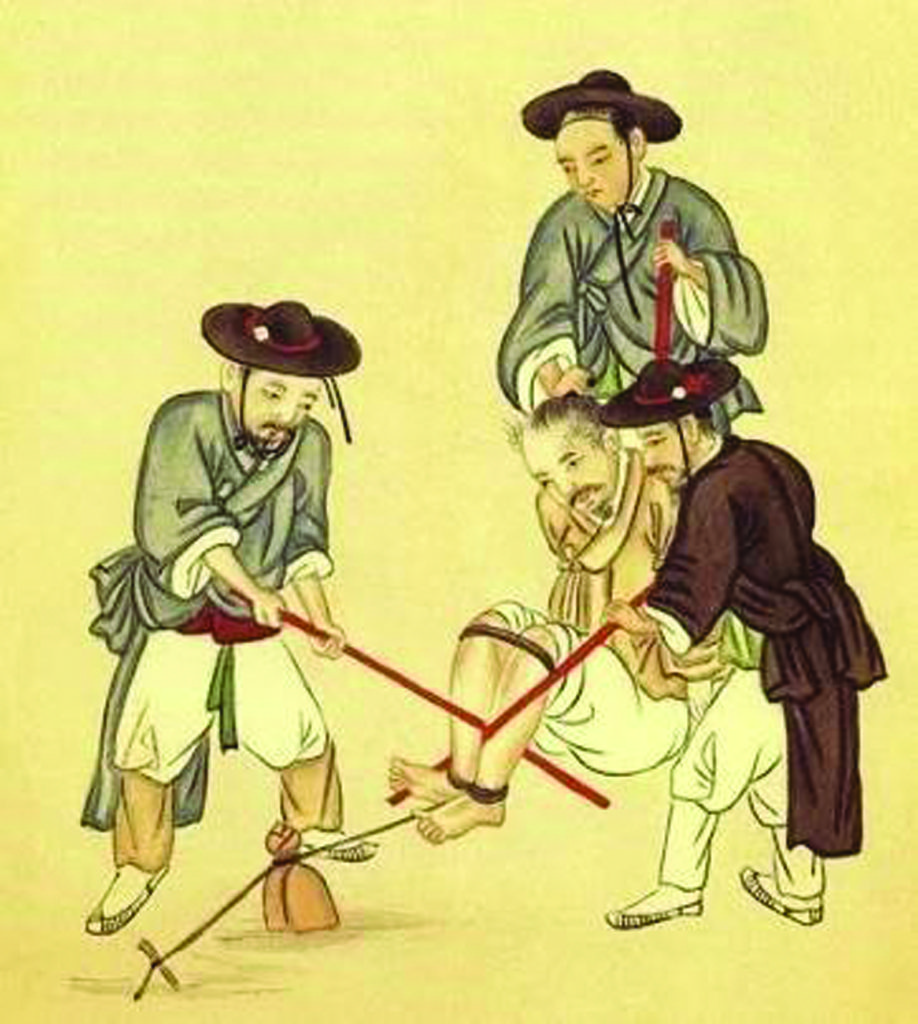

There were a number of customarily practiced extra-legal punishments applied to officialdom. There were also numerous illegal punishments practiced in the private households of the powerful. Back-whipping, leg-twisting (juri-teulgi, 주리틀기), knee-pressing (apseul, 압슬), and indiscriminate flogging (nanjang, 난장) belonged to the former, while hamstringing, nose-cutting, foot-splitting, and ash-water waterboarding belonged to the latter. Leg-twisting was applied to grave crimes such as treason, and it was also used by the police to interrogate thieves and other criminals. The suspects who underwent this leg-twisting process were almost always left crippled for life, and its application was strictly limited.

Back-whipping was used as a means of torture to extract confessions from suspects, but since it was at times fatal, King Sejong, the fourth ruler of the Joseon Dynasty (r. 1418–1450), finally decreed its abolishment. Knee-pressing was also a form of torture in which an extremely heavy object, such as a stone weight, was used to put pressure on the knees of the sitting or squatting suspect. This punishment could also leave the recipient crippled for life. Due to its harshness, King Yeongjo, the 21st king of Joseon (r. 1724-1776), decreed its abolishment.

Indiscriminate flogging was the beating of a victim over their entire body. It too was a dangerous punishment that threatened the suspect’s life and, therefore, was abolished in the 46th year of the reign of King Yeongjo (1769). This practice of indiscriminate flogging, in the form of meongseok-mari (멍석말이, beating of one wrapped in a straw mat), however, lingered on for some time as a popular and customary form of punishment applied to one who violated a woman of high birth or committed particularly immoral crimes such as incest.

Branding, also referred to as stigmatizing, was used when investigating high treason. It was often used when an aristocrat punished his slaves. King Yeongjo, in the 9th year of his reign (1733), abolished this finally, thereby putting an end to the practice. Nose-cutting was applied to privately owned slaves as a punishment by their master until it was strictly prohibited by King Sejong and successive monarchs.

(Courtesy of Korean History Society)

Hamstringing, or cutting of the Achilles tendon, was practiced to control rampant thievery in times of famine. This was a cruel punishment leaving the victim lame or crippled for the rest of their life. It was also randomly applied to privately owned slaves in the households of the aristocracy, which prompted King Sejong to prohibit the practice by decree. However, the practice lingered on in the form of clan punishment or village punishment, similar to “honor killings” in some countries where the perpetrator committed an immoral act.

Ash-water waterboarding (pouring ash water into the nostrils) was a form of torture also applied in the households of the upper class to slaves or the low-born to interrogate them for crimes committed. This, however, in time, also came to be strictly prohibited by the Regulations of the Penal Code.

The penal code of Joseon Dynasty times included a provision that might surprise even a modern-day Korean history buff: a ransom system that, except for certain prescribed crimes, allowed a convicted criminal to make a monetary payment in lieu of their prescribed punishment. This was somewhat similar to today’s system of fines, but this form of ransom was an optional substitute for physical punishments. There were several categories for which ransom was applicable: one applied to social status; one to females, the old, the frail, and the sick; one related to mourning and filial piety to one’s parents; and another was a provision for relief. Penalties for which a ransom could be substituted were stipulated by law and the ransom was collected by a legal enforcement agency. However, there was a sufficient number of cases of irregularities committed by officials regarding ransom collection to often require kings to be concerned with attempting to root out this corruption.

Many of these punishments and interrogation methods carried over into the colonial period (1910–1945), but with the emergence of the Republic of Korea, a completely new penal code was established.

Arranged by David Shaffer