“Class, Do You Understand?”

Written by Dr. David Shaffer

An indispensable element of any lesson taught is checking understanding. How do you, as a teacher, execute this? The convention here in Korea is to ask “Do you understand?” and get the programmed response “YES!” seemingly indicating that you can move on to the next lesson. “Great! We’ll stop here for today, class. See you next time!”

The trouble with this prized teaching technique is that when the students come to the next class or take the next test, many of them have retained nothing, and the teacher realizes the need for a better method of checking understanding. The problem is that the “Do you understand” technique bypasses practice, processing time, and pluck. Merely explaining a word’s meaning, its pronunciation, or its grammatical usage and then asking the students if they understand will generate an automated “yes” response, but little more.

Explanations of new material are helpful, but they need to be accompanied by practice that incorporates the new material. Practice in more than one way is often more helpful than relying on a single activity. The more different associations that one can make with a new item, the more likely it is to be retained and learned. Practice allows for processing time – time for the student to get acquainted with the new item, to consciously figure out how it is to be properly used, and for the brain to do this subconsciously. And pluck. The student needs the courage to speak up. This takes time for many students to build up, but if the teacher does not provide that time when the question is asked, that pluck is plucked. We need a better way of checking understanding – and here we will offer several techniques for assisting the teacher in determining how well their students are understanding the new material.

Exit Tickets

Exit tickets (aka “exit slip” and “ticket to leave”) are a simple and effective method of formative assessment that informs the teacher of how well the individual student understands the class material. It can be used daily, weekly, or whenever, depending on the material covered and the class schedule. An exit ticket is not a quiz; it is a form of written feedback to determine how well lesson material has been understood, or liked, or not understood at all. With the information gained from the students’ exit tickets, teachers can determine what information needs to be reinforced in a future lesson and which students many need different types of reinforcement (i.e., differentiated instruction).

The contents of an exit ticket may take different forms, depending on what type of feedback the teacher is looking for. However, because this is an end-of-class task, the exit ticket should contain no more than 3–5 items, and the responses should be expected to be short. The items inquired about may be in question form (e.g., “What did you like about today’s lesson?”), or they may ask for a list of responses (e.g., “Write down 3 words you learned”). It is often best to not ask yes/no-questions because of the limited feedback they contain. Questions and answers may be in English or the students’ L1, depending on their proficiency level. For young learners, you may wish to have them respond by selecting one of three emoji images: happy, sad, and straight-faced (Figure 1).

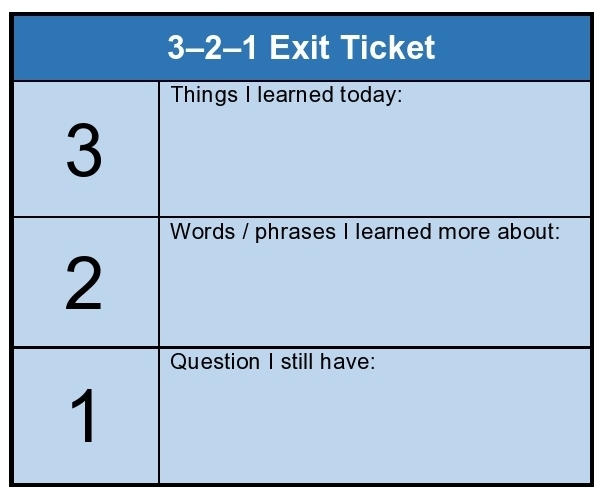

A very common type of ticket is the 3–2–1 exit ticket. It asks for three of one thing, two of another, and one of a third. For example, it may ask for three new things learned, two words or phrases learned, and one question that the learner still has (Figure 2). However, like with any exit ticket, the contents of the 3–2–1 exit ticket depend entirely upon what the teacher wants to know about the effectiveness of the lesson. Exit tickets rely on reading and writing skills, and may be collected as the students go out the door.

Hinge-Point Questions

One should not think of an end-of-class assessment as being the only assessment necessary for gauging the teacher’s effectiveness and the students’ understanding. If the teacher waits until the end of the lesson to assess, a large chunk of valuable class time may have slipped away with the majority of the students in “I have no idea what she’s talking about” mode. Hinge-point questions to the rescue! A hinge-point question is based on a concept in the lesson that is critical for students to understand before moving on to a closely related concept (i.e., what comes next in the lesson “hinges” on a grasp of what has just been presented). It should occur somewhere in the middle part of the lesson, giving time to both present a concept thoroughly and go over it again if needed.

A hinge-point question is designed to produce informative feedback in a minimal amount of time. It should be formulated in such a way that all the students will be able to respond within two minutes, and the teacher will be able to collect and interpret the responses in about half a minute. Hinge questions should be created before class when preparing the lesson, and the percentage of right answers required for the teacher to proceed should be determined then also. These questions are most often multiple-choice in type, but for the EFL/ESL classroom, more open-ended questions are also appropriate.

Going to the Polls

If the teacher is looking for a quick method of getting feedback from the class, a “digital” method may be used. Students may respond to the teachers questions, oral or written, with a physical rating system (showing 1–5 fingers), or the teacher may employ a risk-free, electronic response system such as Socrative or Poll Everywhere to poll the class on their devices. These digital response systems can also be effectively employed for hinge-point questions and exit tickets.

There is no longer any reason for a teacher to walk blindly through their lessons and course. The above formative assessment techniques can easily be applied to receive critical student feedback. No need to rely on “Class, do you understand?”

The Author

David E. Shaffer is Vice-President of the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter of Korea TESOL (KOTESOL). On behalf of the Chapter, he invites you to participate in the teacher development workshops at their monthly meetings (always on a Saturday). For many years, Dr. Shaffer has been a professor of English Language at Chosun University, where he has taught graduate and undergraduate courses. He is a long-time member of KOTESOL and a holder of various KOTESOL positions; at present he is national president. Dr. Shaffer credits KOTESOL for much of his professional development in English language teaching, scholarship, and leadership. He is also the editor-in-chief of the Gwangju News.