More Scandal Than You Can Handle

Russia’s recent pre-emptive disqualification from the 2020 Tokyo Olympics sheds light on the relationship between soft power, corruption, and the institutions that support them both.

Written by William Urbanski.

Well, well, well. The 2020 Olympics haven’t even started yet and Russia went and got itself disqualified (again) for its athletic body’s involvement in a doping scandal larger than Zangief’s biceps. We won’t get into the James Bond-esque details of this massive doping and corruption saga here but, needless to say, a few people in the Kremlin are going to be taken off Vladimir Putin’s Christmas card list, to say the least.

Following all the regulations set out by any international sports competition can be a daunting task, but it seems to me that the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) has some pretty clear rules about getting juiced up on ye olde gym candy. While individual athletes certainly get caught for using banned substances all the time, what’s particular (though unfortunately not very surprising) about Team Russia’s current predicament is its wide-scale, institutional approach to breeding bigger, stronger, and more doping-policy-breaking athletes. Virtually, Russia’s entire athletic program was based on the idea that it ain’t cheating if you don’t get caught.

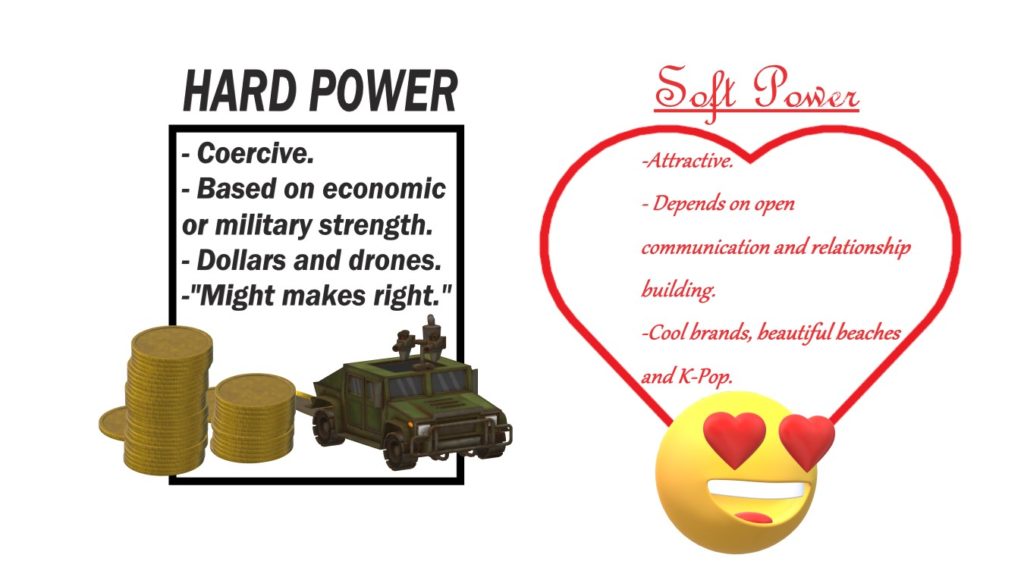

Perhaps you’ve wondered why countries pour so much time and energy into athletic programs anyway. Wouldn’t these hard-earned resources be better directed into fixing poverty or something? After all, if a country wins a gold medal at the Olympics, there’s no big financial reward besides a medallion that, if melted down, is barely worth a ruble. Positive results in sports competitions can definitely be a force for national cohesion and even national pride, but one of the less-obvious reasons countries go so hard into international sports competitions is that doing well increases that country’s level of the ephemeral and elusive concept called soft power.

When wielded correctly, soft power yields a number of economic benefits. If people like a country or have a positive perception of it, they are more likely to visit there or buy its products – it’s really quite as simple as that. America-bashing has become fashionable as of late, but it’s hard to ignore the massive cultural impact the USA has had worldwide because of its excellent movies, music, literature, athletic achievements, and so forth. There’s no question that the reason American products, from Apple to Nike, enjoy so much economic success is because there’s an overall perception that America is, for lack of a better term, “cool.” So what’s up with Russia then? Russia has more than its fair share of cultural achievements (in music, literature, sports, and puzzle-themed video games), not to mention incredible scientific breakthroughs. Surely some of this would translate to increasing soft power and more people admiring all-things Russian, right? Right?

It turns out there’s a phenomenon that works squarely and plainly against soft power, negating it and minimizing its effectiveness. That factor is corruption, and Russia, just like many parts of Asia and Africa, is extremely corrupt.

Hold on, hold on. Before you think I’m “Russia bashing” (which I’m not), let me explain where I’m getting these big ideas from. Corruption is a very measurable thing and there are several well-managed and academically accepted indices that measure and compare it between countries. The one to be familiar with is called the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) run by Transparency International, an NGO based in Berlin, Germany. In 2018, of 180 countries, Russia ranked 138th on the CPI (Korea is 45th, North Korea is 176th).

If you’ve made it this far in this article, I bet you’re just dying to know by what mechanism corruption undermines soft power. Well, today is your lucky day, because I’m going to tell you.

Both corruption and soft power are perception-based and many (myself included) would argue that low corruption is actually a contributing factor to soft power. A quick check on the soft power rankings (my personal favorite is “Soft Power 30”) shows that any country with a high level of corruption cannot maintain a strong degree of soft power. Calculating a country’s soft power may seem like nebulous, airy-fairy pseudo-science, but it’s actually an academically rigorous process that takes into account many factors such as government, education, culture, and enterprise. When a country is perceived as corrupt, what that really means is that its institutions are corrupt and, therefore, produce outcomes that are unexpected, unjust, or just plain unfair. The Russian Federation ranks number 30 out of 30 in the Soft Power 30 ranking, which doesn’t sound so bad considering that they made the top 30 at all, but let me point out that it ranks behind Poland and Turkey, two countries that are complex and interesting in their own rights but aren’t exactly known as cultural heavyweights.

Perhaps you’ve heard a variation of the adage that a man can build a thousand bridges, but if he steals one pig that makes him a thief. In calculating soft power indices, as in life, the bad things we do often count for more than the good things we do. So all the gold medals and sports glory in the world actually count for very little when people think the country that won them is a breeding ground for corruption.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Corruption Perception Index or the Soft Power 30, check out the following links: www.transparency.org and www.softpower30.com

THE AUTHOR

William Urbanski, managing editor of the Gwangju News, has an MA in international relations and cultural diplomacy. He is married to a wonderful Korean woman, always pays cash, and keeps all his receipts.