The Yang-dong Bookmaker’s House

Written and photographed by Isaiah Winters

Gwangju’s Yang-dong neighborhood is a lot like a time capsule. The market there provides a multisensory trip down memory lane (especially where they keep the live chickens), while the surrounding businesses and houses stand as further testaments to another time. It’s a rough, seedy part of town that encapsulates South Korea’s development, warts and all.

Along Yang-dong’s winding Guseong Street (구성로), businesses catering to both spiritual and carnal pursuits share the same space. On one end, fortunetellers sit tucked away behind neon vinyl storefronts ready to impart their augury. On the other end are Amsterdam-style “glass box” (유리박스) storefronts, most of which sit empty. Posing as adult entertainment karaoke bars, they offer their clients a more tangible array of services.

Among the neighborhood’s many abandoned houses, one – a former bookmaker’s house – is particularly noteworthy for its voluminous contents. Doubling as a workshop, the house has half a dozen pieces of outdated machinery used for stamping, cutting, sewing, and pressing books. A few of the machines are evidently quite old, as I could only find photos of them in the online galleries of a few museums and printing shops here in Korea.

A representative from The Museum of Books and Printing (책과인쇄박물관) in Chuncheon, Gangwon-do, kindly responded to my inquiry with some basic information about a few of the machines. One turned out to be a book sewing machine (사철제본기) made by Samwon Machinery (삼원기계). There’s another one just like it on display at a screen printing shop called Pactory (팩토리) in Mapo-gu, Seoul, and an almost identical one on exhibit at the above museum.

Another one of the machines is a semi-automatic cutting machine (반자동재단기) for paper stacks and hardback book covers made by Cho Heung Machinery (조흥기계). Though similar models can be seen in said museum and elsewhere online, it was hard to pin down an exact match. Ditto for the hellaciously heavy antique sewing machine found onsite.

Probably the most visually impressive machine was found by chance during a repeat visit to the house. Hidden behind a door that blends with the wall, a large hot foil stamping machine (금박기) sits idly through its final order. Machines like this are responsible for all that tacky gold and aluminum lettering you’ve no doubt seen stamped on old book covers. What’s visually impressive is the unfurled roll of gold foil it was last stamping on, which makes the machine look like it’s spinning a web of gold.

Less impressive are its final gilded words, followed by my still less impressive translation:

관서운영경비출납부

지급원인행위부

(Public Office Management Expense Accounts Book)

(Purpose-of-Payment Transactions)

On yet another return trip, a smaller replica of this machine was found in a different room with its own little web of gold foil bearing the same stodgy verbiage. As both machines lacked company logos, I had to reach out to a few specialists for further information. Luckily, one from the Book Workshop and Book Art Center (책공방북아트센터) in Songpa-gu, Seoul, was able to affirm that both machines were indeed Korean-made and expressed an interest in coming down to see them in person.

The remaining pieces of equipment are obscured to varying degrees by either rust, collapsed roofing, or heaps of rotten, waterlogged books. Most of the remaining books are simple logs or ledgers used for various sorts of recordkeeping. Fittingly, a few cases of old wooden stamps turned up, looking much like those on exhibit at printing museums. They were mostly engraved with terms in hanja (Chinese characters) and hangeul (Korean alphabetic script), though one randomly bore “Vessel Sounding Log” in English, which is a log used for recording the levels of fuel and waste water in storage tanks aboard ships.

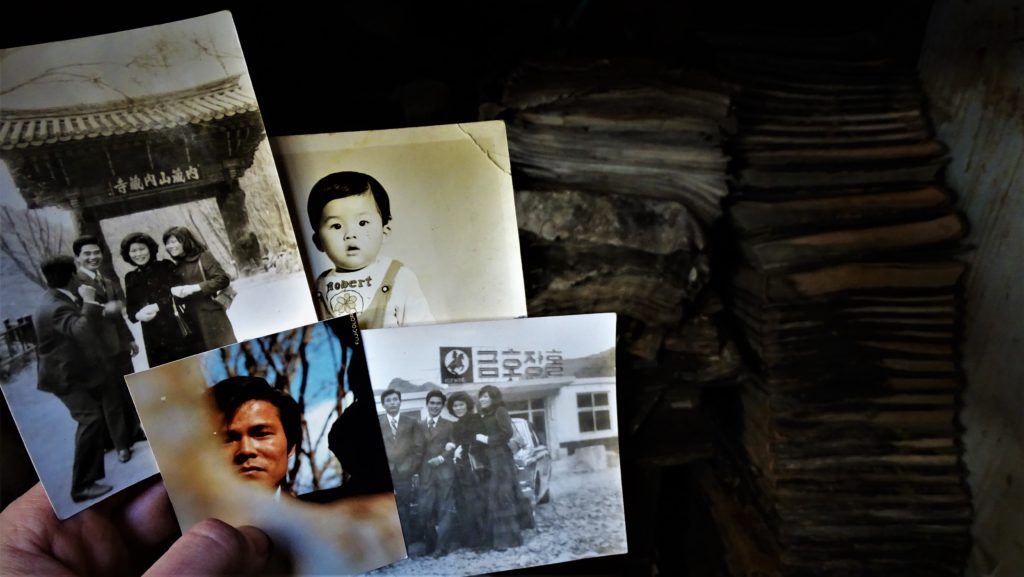

Within the property’s living quarters, there were quite a few revealing personal effects lying around, ranging from candid black-and-white family photos to glossy, nature-themed pornographic magazines from the early 2000s. What stood out most were an incredibly old-looking hanja-to-hangeul dictionary from 1956 and a few black-and-white photos of two young, well-dressed couples visiting a temple together on a road trip.

An honorable mention goes to the Korean-language Kama Sutra book with technical-sounding section headings such as “Sedentary Extended Position,” “Astride Position,” and the world-famous “Normal Position.” Not to be mistaken for a recliner manual, each heading came with explicit imagery, detailed information, and even an approximate geometric shape, giving the book that extra nerdy touch.

There’s one more intact room at the bookmaker’s house that I’ve yet to see, though I’ll probably save it for the future – the very near future. Much of the area won’t remain in its current state beyond a few more years, as it’s being redeveloped bit by bit. Just in the last month, the former Agricultural Cooperative’s Gwangju Marketplace (농협광주공판장) on the fortunetelling end of Guseong Street has been cordoned off by that inauspicious combination of scaffolding and pastel construction fabric. It’s surely a sign of things to come.

THE AUTHOR

Originally from Southern California, Isaiah Winters first came to Gwangju in 2010. He recently returned to South Korea after completing his MA in Eastern Europe and is currently the new chief proofreader for the Gwangju News. He enjoys writing, political science, and urban exploring.