Isaac’s Storm by Erik Larson

Reviewed by Michael Attard

I read this book after reading three of Erik Larson’s other books, which I had enjoyed immensely. Otherwise, a history/science book about a hurricane would probably not have drawn my interest. I was not disappointed, although I found myself less punctilious when reading some of the scientific passages. But for those interested in science, particularly the weather, the discussion of isobars, barometric pressure, centrifugal force, and ocean swells may be appealing.

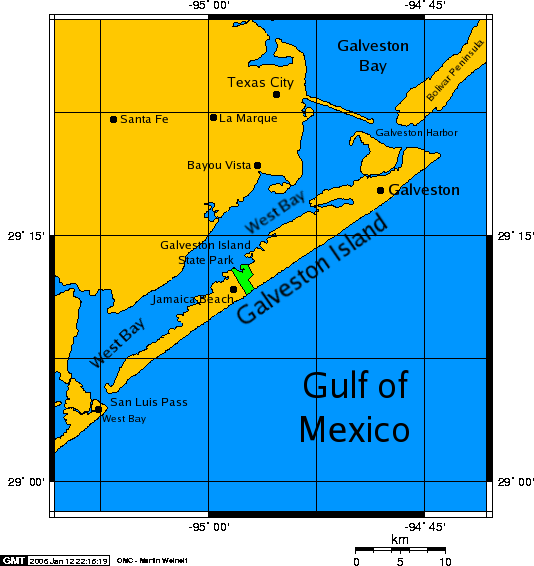

The central character is the real Isaac Cline, born in 1861. Like most people of his time, he was born on a farm. But unlike others, Isaac pursued education and his love of science. He said, “I made up my mind that I would seek some field where I could tell big stories and tell the truth.” He chose the weather. In 1889, he took over the Galveston, Texas, weather station. The city is built on an island off the Texas coast in the Gulf of Mexico. The highest point was 8.7 feet or 2.65 meters above sea level.

We do not generally think about it, but all of our institutions had a beginning, including the weather service. In the United States it began under the auspices of the U.S. military’s Signal Corps in 1880. It may seem strange to us today, but at the time, its founding was controversial. Consider, this was a time when lightning was barely understood, tornadoes not at all. “Some critics argued men should not try to predict the weather, because it was God’s province.” Also, weather predictions had a poor record. It was a time when captains regularly sailed their ships into the worst of storms and weather forecasting was a list of probabilities.

Along with Isaac, the author introduces his wife Cora, their three daughters, Isaac’s brother Joseph, and a multitude of other characters depicting an optimistic life at the end of the 19th century. Everyone in Galveston had experienced storms, but for the most part, the citizens, including Isaac, did not fear that a hurricane could hit Texas.

In the first part of the book, there are many stories about earlier hurricanes, some of which had profound effects upon history. The author relates experiments by scientists such as Galileo, the results of which astonished the leading scientists of the day. In one such experiment, Galileo proved that air had weight. The significance of this was not immediately recognized, but it would have an immense meteorological significance.

Much of the story revolves around the politics and bureaucracy of the weather bureau. Larson does not directly conclude that the loss of life in Galveston in 1900 was due to mismanagement, but I think he makes it easy for the reader to connect the dots.

In the U.S., there was a long-standing disregard for information gathered and disseminated by the Cuban weather service. The sentiment was that the Cubans were too quick to use the word “hurricane,” thus leading to unnecessary panic. Authorities went as far as to ban all cables about the weather sent over Cuban-owned telegraph lines. It is important to note that this was at a time when Galveston was in stiff competition with Houston for becoming the major port city in the gulf. Hurricane worries were counter to Galveston boosterism.

But the hurricane did come. And Larson gives us an account of the devastation it wrought upon the community. The sturdiest of homes were swept and blown from their foundations, pulled apart by wind and wave, and sent on by the forces of nature to crash into and destroy other structures, striking and killing man and beast along the way. St. Mary’s orphanage looked like a fortress of brick. Would the 93 children and ten nuns survive? On a train carrying 95 people, 85 decided that it was best to stay put. Ten decided to leave. Who made the correct decision? Isaac had his daughters, but where was his wife? Large ships anchored when the storm hit. Were they still there the following morning?

It took a few days for help to arrive and even longer for most to comprehend the magnitude of destruction and death. While many “bore their losses quietly,” and “grieved without demonstration,” there was no escaping the “scent of putrefaction.” With intense heat, it became clear that burning of the bodies was necessary.

In the aftermath, how did Isaac feel? He was the respected weatherman, but he had obviously not seen what was coming, at least not until it was much too late. Was he responsible in some way? He may have felt so, but this did not stop him from taking credit for saving thousands of lives. Larson, the author, does not act as judge. He simply does not know enough to conjecture what Isaac thought, knew, should have known, or should have done, or at least he does not say so.

We do know, however, that Isaac wanted to have his say but could not. Would an acknowledgement of failure change anything? Did Isaac have a responsibility to protect the credibility of the weather bureau? There was evidence, however, that Isaac quietly disputed claims that hurricane warnings had been raised. Then of course, there was one simple, all-encompassing question: “If the bureau had done such a great job, why did so many people die?” It appears that at least 6,000 people died, but estimates are more than 10,000 if those who perished in low-lying towns on the mainland are included.

I do not know why Erik Larson chose to write this book, but reading it reinforced my belief that life is fragile, the unexpected does happen, and we need to respect nature in all its forms.

Isaac died in 1955 at the age of 93.

The Reviewer

Michael Attard is a Canadian who has lived in Gwangju since 2004. Though officially retired, he still teaches a few private English classes. He enjoys reading all kinds of books and writes for fun. When the weather is nice, you may find him on a hiking trail.