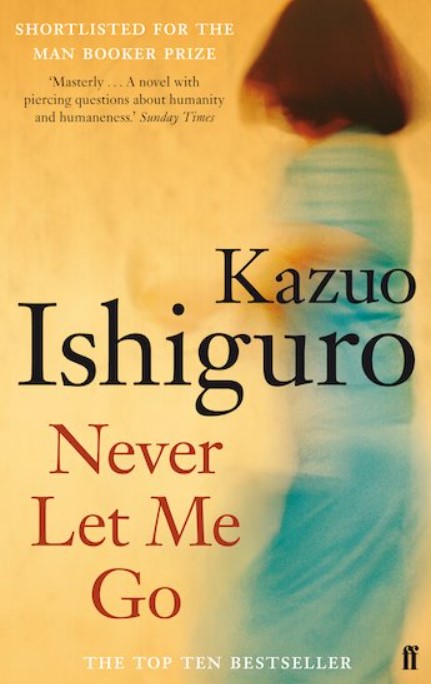

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

Reviewed by Michael Attard

The children are living in what appears to be a private boarding school for a select few, but something is amiss. There is no mention of family visits, going home for the holidays, or from where the children come. The main character and narrator, Kathy, tells us, “We knew a few things about ourselves – about who we were, how we were different from our guardians, from the people outside – but hadn’t yet understood what it meant.” And it is clear that the dissimilarity is not perceived as a good thing for the children. There are people who “shudder at the very thought of you.”

The three main characters are students and have grown up together. In addition to Kathy, there are Ruth and Tommy. The author, Kazuo Ishiguro, through their conversations gives us an in-depth view of their personalities and emotions. They often disagree and can be quite mean to each other, but having each other is all that they possess.

The story is told through Kathy’s memory. At times, her recollections go back many years, and in other instances not as far, but even then, the subject of conversation may revolve around an older memory. The accuracy of memory, for all the characters, is often brought into question. Kathy, as narrator, regularly admits to not being quite so sure of events, and she realizes that her levels of understanding were subject to maturation. At times, there are wide discrepancies in memories. With respect to an imagination game that Kathy and Ruth used to play, Ruth claimed that they had only played the game for two or three weeks. Kathy says, “My guess is that it went on for nine months, a year even.” This recurring theme of memory and forgetfulness is employed by the author to cast doubt upon the readers’ mind about the veracity of our own perceptions – as if all of us are in a world different from what it seems.

Early in the story, we learn that the title of the book is taken from the song “Never Let Me Go.” Kathy had the song on a tape but would only play it when no one else was around. She was eleven years old at the time, and even though she suspected that she misunderstood what the song was about, she says, “that wasn’t an issue for me. The song was about what I said.” This falls in line with the author’s questioning of memory and the subsequent chosen beliefs by which we live our lives. As the characters become older, they are sometimes able to objectively fill in the blanks as to who they are. This is not to imply that they understand the “why” of their situation. In addition, there is the question, “Are they good enough?” This is mainly expressed through the character Tommy.

There are several minor but significant characters such as Miss Lucy, one of their teachers, or guardians, as they were called, and it is she who tries to break through the illusion of a free life in the future. Relatively early in the book, it becomes clear to the reader that the birth, lives, preordained purpose, and early death of the children is part of a macabre master plan created by a power elite. Yet mystifyingly, there is never talk of revolt.

There are a few sub-plots such as a mysterious gallery where the students’ art work supposedly goes. There is rumor of a deferral plan which would delay the inevitable. There are side trips, taken with the hope of shedding light onto their situation, and there is even romance. But while the conversations and activity progress at a quick pace, I was left wondering about the purpose of the sub-plots. Perhaps it is to create a hope, even if in the end, there is no chance of escaping the unavoidable.

It strikes me however, that even the story’s main plot line is secondary to the author’s purpose. The actions, friendships, arguments, unknowns, revelations, and fluctuating emotions seem simply to be a façade for an unnerving and gloomy existence. No matter what they do or what happens, there will not be a positive result. The meager attempts at hope only reinforce the sense of failure. Toward the end, Kathy tried to keep out the feeling “that we were doing all this too late; that there’d once been a time for it, but we’d let that go by, and there was something ridiculous, reprehensible even, about the way we were thinking and planning.”

I will venture to say that Ishiguro has an existential view of life. How else to explain the suffering and the absurdity of life? But even in negativity he poses important questions pertaining to the existence of the human soul. These questions override the mundane details of what we mistakenly interpret as our essence.

In conclusion, I have tried to interpret Ishiguro’s message which transcends his story. I am not saying that I agree or disagree with his perspective. But if you are interested in reading a book delving behind the prosaic scenes of life, you may find that this book opens a few new doors.

The Reviewer

Michael Attard is a Canadian who has lived in Gwangju since 2004. Though officially retired, he still teaches a few private English classes. He enjoys reading all kinds of books and writes for fun. When the weather is nice, you may find him on a hiking trail.