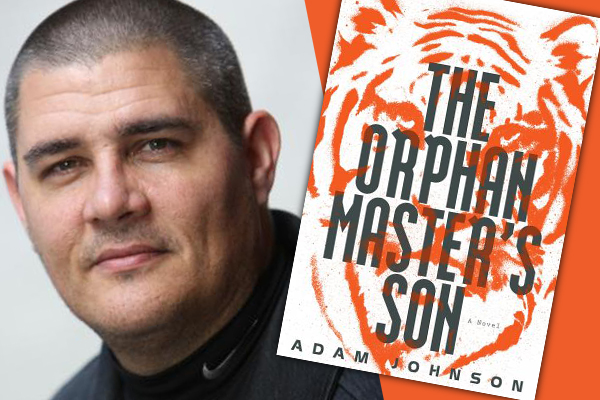

The Orphan Master’s Son

Written by Douglas Baumwoll

So, I get home from work, hurl my backpack onto the bed, tear it open, plunge my hand in, grope around in the mélange of papers, computer hardware, and gym clothes, and . . . No! It’s not in there! I left my book at work!

This really happened. And worse, I was on page 425 of this 443-page book, and I still had no clue as to how it would end. It’s been a while since I’ve read a page-turner like The Orphan Master’s Son, but now the drought is over.

Adam Johnson weaves a spellbinding story that harkens back to visionary dystopian works like Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World. The difference here is that Johnson’s totalitarian state is that of modern-day North Korea, which brings the whole experience closer to your world reality (especially if you live in South Korea).

Now, as you start your journey with the protagonist, Jun Do, you must keep in mind that the plot and characters are “a work of the imagination.” (Although Johnson completed “a tremendous amount of research” during the writing.) The third-person subjective narrative details Jun Do’s life in rural North Korea, growing up in an orphanage. Johnson uses this plot device to align you with the particularly pitiable fate of orphans in the real-world Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. He effectively calls your attention to real-world calamities in North Korea throughout the novel. “[Many] details in the book are fact-based,” culled from Johnson’s investigations, defectors’ testimonies, and a one-week visit to the Hermit Kingdom.

The narrative next follows Jun Do’s life in the military. Jun Do is dutiful and commits immoral acts against other human beings, but Johnson manages to get you to understand Jun Do rather than condemn him – no small feat of the writing craft. Perhaps part of this achievement is due to the main character’s name: Jun Do. This name invokes in the English-language reader the concept of “John Doe,” meaning the grievous journey you live through with him could be that of any boy in the fictional or real North Korea. You empathize with him throughout, and feel his dismay when he is unable to defect when he has the chance. For if he does, all of his friends and coworkers would be sent to prison camps to labor as slaves and die within a few years.

Part Two of the book begins with a new, first-person narrative voice of an intelligence officer. You now learn about the lives and motivations of Pyongyang’s power elite, as well as those of the Dear Leader, Kim Jung Il. You experience his propaganda machine through a third narrative voice, that of “the loudspeaker,” which bellows absurdities from which no one is spared, not even when inside an apartment building.

Johnson incorporates many aspects of Joseph Campbell’s “hero’s journey,” and Jun Do undergoes major transformation. At this point in the story, he entertains no fear of pain or death and is therefore immune to the state’s controlling influence. He finds love for Sun Moon, the country’s only actress, whose role promotes a fable-like devotion to the Dear Leader and Juche, the state’s philosophy of “self-reliance.” Jun Do’s love for this woman and her two children motivates him to live in a complex society where the challenge is, according to Johnson, “to retain your humanity, without losing the survival game.”

The final main character I will mention is the Dear Leader himself, Kim Jong Il. Johnson has been criticized for including this character, and surmising about the real Kim’s motivations. Yet, Johnson says that because one man literally wrote the script for an entire nation, a nation where “spontaneity can’t exist, where revealing yourself, and your true inner thoughts . . . might have grave consequences,” he was forced to include Kim in the story. “The difference between fiction and nonfiction is that fiction must be believable. And a lot of the nonfiction of North Korea is not believable,” says Johnson. So he tries to humanize a globally vilified leader, showing his vulnerability, strengths, weaknesses, and intelligence.

The climactic scene, almost on the last page, has a slight slapstick feel to it, and I am not sure it is 100% believable, but it did not detract from my appreciation of the story and perhaps adds a slight comical element to a novel rife with heavy issues pertaining to the human condition and authoritarian government behaviors.

The Orphan Master’s Son won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2013. Despite a few possible shortcomings, you should read this book. If you live here in South Korea, you will realize that some prevailing cultural attitudes exist in both North and South Korea alike. You will learn factual information that may inspire you to learn a bit more online. I am reminded of Khaled Hosseini’s books or Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, which, despite being fiction, educated me about the calamitous lives many led in Afghanistan and Nigeria.

Johnson’s descriptive language is elegant and at times poetic, and the characters’ direct speech is loose and informal, and absolutely contemporary. His philosophical insights into the human condition are incisive and force you to consider not only life in North Korea, but in all countries. He has stated that “one of the questions of the novel is what does it mean to survive when you have nothing to live for?” And this is something we must all consider, to some degree, wherever you are from or wherever you live. In addition, I found myself constantly considering absurdity and truth-denying policies of the ultra-conservative government currently in power in my own country, the United States. Where does the U.S. currently stand on the slippery slope down into totalitarianism, oppression, and denial of human rights? Clearly, the United States is no North Korea, but at least a dozen times in the story, I found myself relating scenes I was reading to actual happenings and people in the real world.

At one point, Jun Do thinks about “reminding the Dear Leader that they lived in a land where people had been trained to accept any reality presented to them . . . how questioning reality . . . simply noticing that realities had changed” could lead to dangerous ends. Alas, it seems Jun Do’s imaginary North Korea shares at least some similarity with my own real-world home country. Does it share any with yours?

For further information on the reality in North Korea, check out the stories of Lee Hyeon-seo, Joseph Kim, Shin Dong-hyuk, and Park Yeon-mi. All have written books and appear in multiple videos online.

The Author

Doug Baumwoll, a professional writer and editor for 25 years, trains in-service teachers in writing skills and methodology. His personal writing interests include visionary and speculative fiction, climate change, energy, and social justice. He is the founder of SavetheHumanz.com.