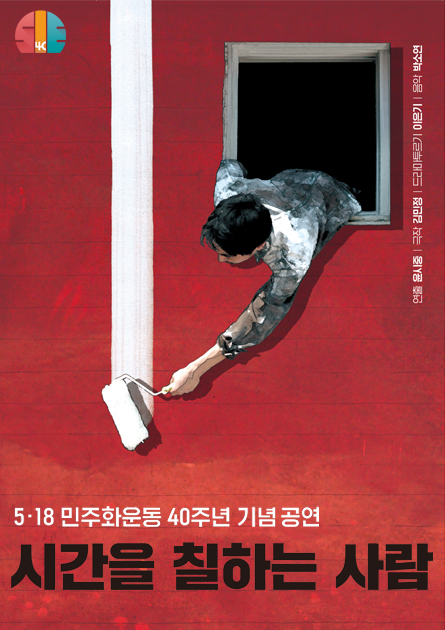

“The Man Who Paints Time” (시간을 칠하는 사람)

Reviewed by Viktoryia Shylkouskaya.

Photographs provided by the Asia Culture Center.

You probably know what 4D cinema is, where your seat moves in sync with the movie action, allowing you to “feel” the movie’s motion. But have you heard about 4D theater play, in other words, a “black-box” or “flexible-seating” theater? The ACC’s “The Man Who Paints Time” is one of them!

Recently, I had the pleasure of seeing one of the performances of “The Man Who Paints Time” at the ACC, timed to the 40th anniversary of the May 18 Democratization Movement. At first glance, the performance space looked more like an industrial warehouse than a theater. You enter a very big, dark room with an impossibly high ceiling. In the dark room, you only can see a five-row seat module facing one of the walls of the room. The wall is decorated to resemble a three-story building, which makes it look like a construction site. Surprised at first, I mistakenly thought I had been led on a sort of backstage tour. But no, I was at the right place. This form of theater space is called a “black-box” or “flexible-seating” theater. Either of these names is actually quite descriptive. This type of theater is generally housed in a large, black, rectilinear room. In such a space, audience seating may be moved around, allowing the performance area to flow through and around the seats, while the use of risers helps facilitate better sightlines.

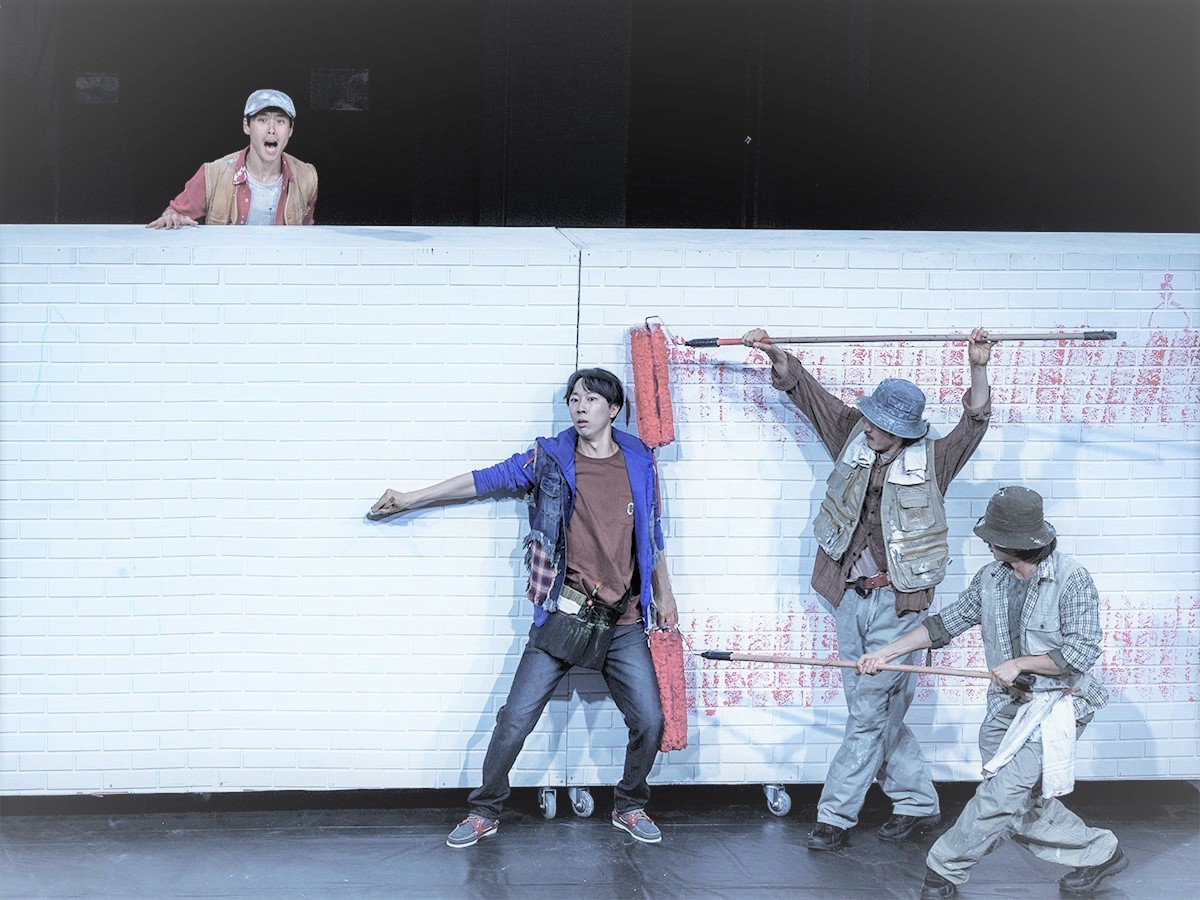

The play starts. It gets incredibly busy in front of the building with construction workers, some locals, and passers-by. It is only three meters from where I am sitting to the actors. We hear the sound of a bulldozer, which is about to demolish the building. Suddenly, the seating platform holding the audience starts rolling towards the building, and I understand – we are the bulldozer that is moving to ram the building’s walls. Someone shouts: “Person in the building!” All the attention follows the light to the third floor. We see a man with a brush in his hands. It is Kim Young-sik, a man who cannot allow the demolition of the building because its walls hold the memories of past years. Every brick in its walls holds memories of his wife and son, who fell victim to a brutal military crackdown in Gwangju in 1980. These walls remember his entire life; these walls remember everything. The man suddenly jumps out of the window and the lights go down. To be honest, it is only five minutes into the play and I have already gotten goosebumps! It is the most unusual start to a play I have even seen.

The lights come on again and we are back in time. The play tells us the story of the building with white walls and people who work there. The building is the former Provincial Office of Jeollanam-do, which later became the center of the May 18 Democratization Movement that unfolded in Gwangju in 1980. Kim Young-sik is one of the workers who is tasked with painting the facade walls of the building. One day, he meets the love of his life, Myung-sim, an office worker from the same building. Their love story starts from sharing an apple. We see apples so many times throughout the performance because the play employs a large number of metaphors. “Apple” (사과, sagwa) in Korean is pronounced the same as the Korean word for “apology,” making them homonyms. Throughout the play, the son of Young-sik and Myung-sim will eat apples while talking with his parents; later while busy with work, Myung-sim will give an apple to her son while he waits to play with her. It is a metaphor the Korean people use to say “sorry.” People that have been killed or injured in the May 18 military crackdown as well will receive apples, and finally, almost at the end of the play, old ladies with apples will wait for Myung-sim after her death.

The white walls of the Provincial Office can be interpreted as well as a symbol of authority and power, things that are put in order, and political subordination. On the other side, the colorful paint stands for young activists who are not scared to make a difference, a symbol of the much-needed spark for large-scale change in Korean society. The child with colorful crayons symbolizes the importance of today’s youth building our future. Painting with colors represents the voice of a young generation that is not scared to stand up for what it believes in, especially at a time when adults are butting heads over policies and politics. At the end of the play, the son of Young-sik and Myung-sim gets killed while painting on the white walls of the Provincial Government Office. Two contrasting red lines on the white wall left after a tank rolls through is a symbol of the bloody political history of Gwangju and South Korean democracy.

The play is definitely an emotional rollercoaster for the audience. The mobile audience seating platform moves from place to place during the performance, blurring the boundaries of performance art. Scenic elements become less important in the black-box theater, although lighting, props, and sound retain a great deal of influence. The actors have put together an amazing show with smooth scene changes, a clear focus, and a cohesiveness that is both impressive and unmatched.

I encourage you to go see a performance of “The Man Who Paints Time” when it returns to the ACC. Hundreds of theaters across Korea are putting on different plays, but I guarantee you will not find one quite like the ACC Theater’s rendition. If you want to get a unique chance to go through what Gwangju people have gone through and experience what a 4D theater play is like, then come out and support these fine actors!

Location: ACC Theater, 38 Munhwajeondang-ro, Dong-gu, Gwangju 61485

Information on previous plays

Date: October 16–20, 2019; May 27–31, 2020

Time: Weekdays 19:00; Saturday 15:00, 19:00; Sunday 15:00

Price: 30,000 KRW

*The show is expected to run again in October 2020 or May 2021

**Tickets sell out really fast, so hurry up and buy them for the next season!

For more information, visit https://www.acc.go.kr/

THE REVIEWER

Viktoryia Shylkouskaya is a 25-year-old Belarusian currently residing in Gwangju. She moved to South Korea in 2016 without any knowledge of the country or language. What she thought would only be one year has since turned into many more. Instagram: @shylk.vick