The Morning Calm of Ink Wash

Written and photographed by Saul Latham

Korea’s morning calm is drifting. Excited by the power and speed of international currents, Korea floats on the lips of new technological waves, wrestling, like many other cultures, with a whitewash of postmodernity and globalization. On the face of it, the veneer of Korea’s cultural identity sometimes seems thin. Traditions have been peeled away or lay stitched in behind new alternatives. sumuk-hwa (수묵화, ink wash painting) is one such tradition of Korean culture. Submerged beneath the white water of cultural waves, sumuk-hwa can only go with the force, rolling and spinning, and sometimes rearing its head out into the open. At the 2018 Jeollanamdo International Sumuk Biennale, sumuk-hwa was offered to the world. Who was looking?

It’s the first day of autumn, and I’ve come down to Mokpo for the opening of the Biennale. The Mokpo Culture and Arts Center sits on the water’s edge, part of an impressive cultural belt that includes the Natural History Museum and Maritime Museum, amongst others. Surrounding this belt are typically majestic Korean hills that offer views from below and above. There’s a whole heap to do and see here, if only I had a few more hours – but I’m here for the sumuk-hwa.

I’m here to learn what I can about sumuk-hwa and the Korea of old and new. So, making my way to the venue, I try to keep in mind the privilege of my position. As a legal alien in this graceful country, an Australian in Mokpo, I wish to respect traditional culture, modern perspectives, and diversity of thought. As a writer, however, I must write with the freedom of responsibility and to express what I see as being important.

sumuk-hwa literally means “water-ink-painting.” The Korean form is created using traditional materials and techniques of East Asia. Works are usually made on silk or hanji (한지) paper using brushes, and often with black ink diluted with water. Some time ago, sumuk-hwa became known for the self-cultivation and expression of Koreans. Is it still known as such, today?

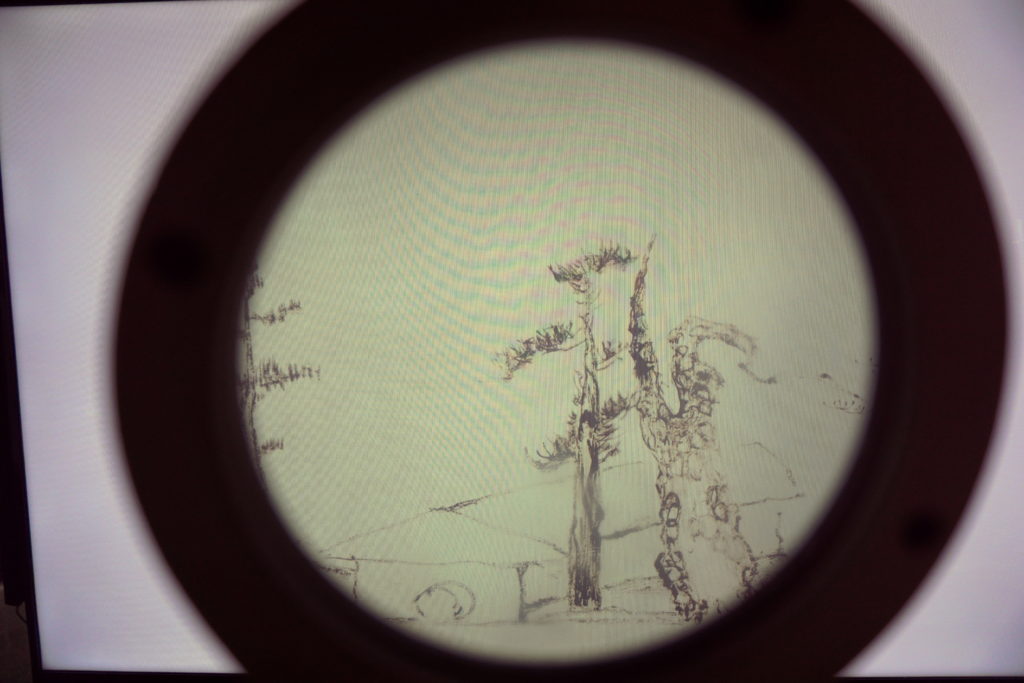

Upon entry, to my left is a large projection of animated sumuk-hwa layers. I stand in front of the moving images, my silhouette cast amongst the changing contours. Nearby, four screens display multimedia works by the same artist, Lee Lee-nam. At a blank white screen, a round viewing utensil leads my eye into a scene where another animated sumuk-hwa is revealed. A man looks out over valleys and mountains. I’m carried through an atmospheric gray-toned landscape and over trees and mountain peaks to a woman in period dress holding an umbrella. The piece exudes a calm and peaceful aura. The land of the morning calm is touched.

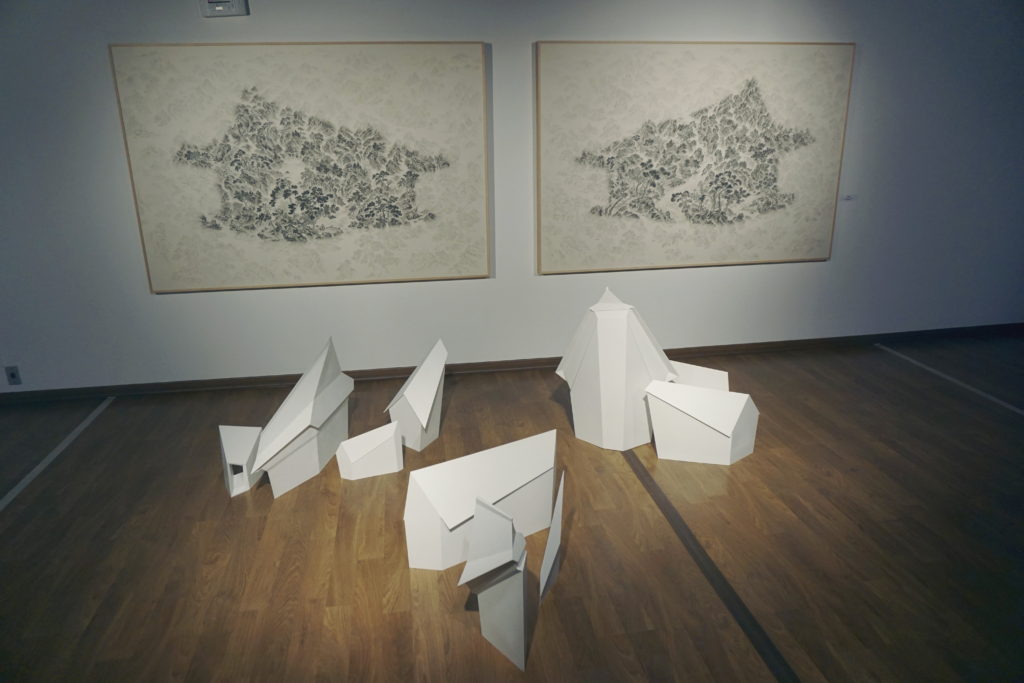

On the other side of the room, a folding screen plots black sumuk-hwa mountains in front of a see-through sky. Geometric shadows fall behind with uniform beauty. In the corner, sheets of transparent film suspend from the ceiling, filed one in front of the other. On them, black shapes are layered out into a space multiplied by the movement of light through the work. A hazy atmospheric horizon is imagined. The sheets of film are spectacularly transformed, with subtle bending refractions and bright reflections granting the beholder a rich encounter from any perspective. The artist is Jin Hyun-mi.

On the first floor of the building, light falls from above as I walk through the central atrium. A central staircase puts old and young folk onto any of the three levels of the exhibition. Massive ink prints dangle from the ceiling to the floor. I follow my nose and round the corner to the first exhibition space, where the abstract minimalism of Seo Yong-ju is shown beside the romantic minimalism of ink done by Lim Hyeon-nak and the meticulous designs of Jo Jung-seong. There’s even alien-esque heads isolated in small elliptical pieces by Kim Jung-wook. The range of style is wider than I’d imagined. Already, I’m wondering what the parameters of sumuk-hwa are, and I’m more confused about the state of this art.

The scope of Korean sumuk-hwa has branched out from historical subgenres into ever-changing new ones. Historically, the main subgenres were gunjeong, jiyeong, and munin (literati painting). Realism in sumuk-hwa came from the landscape paintings of the gunjeong and jiyeong schools. Munin was practiced mainly by the yangban (양반), a scholarly ruling class of the Joseon period. During the mid-17th century, the Silhak (실학) movement – a pragmatic and progressive Korean Confucian reformation – converged with munin, moving it towards more abstract ideals with a distinct Korean refinement. This era defined Korean sumuk-hwa with the help of prominent figures such as Kim Jeong-hui. Today, the strokes of the art continue to evolve in color and black ink.

On level two, my attention is grabbed by Cho Yeong-baek’s masterful classical painting of a town set amongst misty hills. With skill, the artist envelopes an eternal morning calm atmosphere from somewhere in the back of my subconsciousness. To say that it reminds me of something that once hung at my grandmother’s house is a downright slap in the face of such quality, but I really feel a strong connection to this painting.

Sumuk-hwa doesn’t just seek a mere representation of form. It aims to uncover the essence of energy, the movement of life, the expression of growth and change, spirit and vitality. These themes are picked up in the 3rd Exhibition Hall. Kim Ho-deuk’s unhesitant thick dashes of inked lines produce a powerful energy in a strong traditional style. Seong So-ryun’s application of water transforms his paper medium into an embossed and brooding visualization of a mountainous landscape. Ghost-like characters are mixed with calligraphy and loose strokes in Gang Gun-go’s spacious and lighthearted spook, painted on plywood.

Over centuries, Korea, China, and Japan have owned and cultivated the meditative qualities of sumuk-hwa and its sibling styles. Sumuk-hwa has existed in dialogue with the values and aesthetics of these cultures, both directing culture and borrowing from it. As modernity brought Western art to the shores of Asia, the traditions of sumuk-hwa were challenged. This process still continues today.

The 5th Exhibition Hall compares the evolution of sumuk-hwa by showing works from all three countries. The variety is obvious, but a particular national style is hard to pinpoint from my uneducated perspective. What does stand out to me is Kira Yoshi’s Shouhukugassen, a cartoon-like depiction of an altercation between a cat and a fish. In the work of Korean Ga Eon-jong, classicism is maintained and extended, with finely detailed line work depicting three large entangled jungle trees. Pink dots of ink fill Chinese artist Li Guanping’s canvas with softly fixed simplicity, while Zaho Baoping shows a lighthearted comic-book-styled series subjecting domesticity, humanity, and daily life to the brush. In Nebula Series No. 4, JiZi takes the sumuk-hwa style into outer space with a less traditional approach somewhere within Western Realism.

The essence of sumuk-hwa is to give force and spirit to the lines through the brush. Traditionally, calligraphy and painting weren’t separated. Modern sumuk-hwa shares the pursuit of literary and figurative forms with older traditions. Yet, the processes and outcomes of these lines are determined by more than just ink, paper, and the brain’s hand. Hands now work through the emerging brains of computers. Mediums diverge further into experiments.

Once upon a time, sumuk-hwa was the measure of one’s intellect and character. As the heart composed the brush and the brain measured ink, the eyes restrained the hand and the lungs steadied the wrist; the artist was close to his/her work. I suspect this was/is the heart of sumuk-hwa. What relationship is left between the artist and the work in forms that don’t demand this same process? These days, we do a lot of scrolling and clicking. Expressions from the hand are lost to the might of human endeavor. Meaning is made, lost, and turned upside down by the zeitgeist. I wonder about the hard lines of sumuk-hwa – have they become too soft? What would the Joseon-period artists think of these new approaches? How far can an art form change before it becomes something else? Lines are important.

On the top floor, I’m met with color – reds, turquoise, gold, and yellow. Hul Jin’s modern take on sumuk-hwa depicts an abstracted horse, an elephant, a car, and people. The dotted approach reminds me of the traditional style made famous by Australian indigenous peoples. I circle the floor perimeter and come to what seems to be a very important piece.

Outside of the exhibition, I’m fumbling with objects in my bag when a man asks if I need assistance. “I’m looking for the second exhibition space.” He kindly helps and points out that there is a free shuttle bus leaving Mokpo for Gwangju at five o’clock. I come upon the participatory part of the exhibition. I sit down next to some elementary children and attempt my own sumuk-hwa. Attempting to imitate the old-school hands, I brush mountains, trees, and a river on the hanji paper. My picture comes out alright, but I’ve applied too much dark ink. The children next to me are experts, copying faces and shapes from their phones with ease. I feel like a child – and that’s okay.

It’s now nearly five o’clock. I bid the friendly folk goodbye with my minimal Korean. One assures me he’ll see me next time. I jump on the bus, and it appears I’m the first passenger. Then, as the door shuts and the driver asks “Gwangju?” I realize I’m the only passenger. He hands me the television remote control.

I wonder about Korea, about Korean art like sumuk-hwa, about the economics of all this. I feel a bit special and a bit sad being on the bus alone. “Where are all the sumuk-hwa-lovers?” I think with naivety, ignorance, and justification. Where are the artists? Maybe they’re at home in their own heads, in studios, or on the island-like mountains that spring out above Korea’s cityscape. I hope sumuk-hwa isn’t being eroded by the intensity of global progress and cultural transformation. I’m hoping Koreans can keep traditions like sumuk-hwa above the water.

The Author

Saul is a Tasmanian based in Gwangju who can’t get enough of kimchi mandu (김치만두). His job is to teach, but his work is to write. When freed of these, he constructs MIDI compositions on the computer, tries different flavored milk, or goes for a walk.