The End Is Near!

Mangnyeon-hoe

As the end of the year approaches in Korea, it is customary for groups of friends to gather around a table for dinner, conversation, remembrances, gaiety, and often alcoholic beverages. Over the years, as Korea has transformed as a nation, the name by which these get-togethers have gone has also experienced change. Prof. Shin Sang-soon wrote about this in his The Korean Way column in the January 2006 issue of the Gwangju News. That article, “Mangnyeon-hoe, the Year-End Party,” with some additions, has been resurrected for this end-of-year issue of our magazine. — Ed.

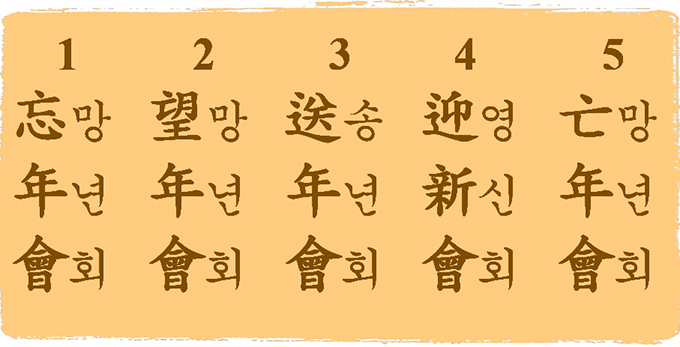

As the end of a year nears, many Koreans, especially those in the 20–50 age bracket, will feel obliged to attend several social gatherings at which some kind of alcoholic beverage, strong or mild, depending on the occasion, is likely to be served. The meeting will be of school classmates, alumni, colleagues, or of business associates, friends from the same childhood village or town, or other affinity group. If the get-togethers take place in the latter half of December, one may have something scheduled for almost every other day. By their nature, these meetings may be generalized as year-end gatherings to reconfirm friendship with each other. These end-of-year events have gone by various monikers in Korea. The first of these was mangnyeon-hoe (망년회; see No. 1 in Figure 1), whose Chinese characters give it the literal meaning “forget-the-year meet.”

This name was widely used in the colonial days when times were tough for Koreans while under the heavy-handed rule of Imperial Japan. Almost immediately after the end of colonial rule, the Korean War (1950–1953) broke out and devastated much of the already-impoverished peninsula. With all of the hardships that Koreans had to endure throughout any single year in those times, there is little wonder that people wanted to forget the bad times that they had endured, and the name for these year-end get-togethers stuck: mangnyeon-hoe.

As Korea was transforming from the underdeveloped nation of the 1950s and 1960s into a developing nation in the 1970s, industrialization was taking hold and the decade began to record double-digit annual growth rates. Life was not as harsh – indoor plumbing was no longer unheard of and portable TV sets were appearing in living rooms for the first time. People began to have a more positive outlook on life, and this positivity began a trend to change the Chinese characters for mangnyeon-hoe (see No. 2). With a single character change for mang, the more-upbeat meaning of mangnyeon-hoe was transformed into “looking-forward-to-the-coming-year meet.”

Since the two terms (No. 1 and No. 2) were homophones and their meanings referred to the same year-end event, the only real discrepancy came when writing them. At the time, Chinese characters were still widely used in the print media – instead of the Hangeul alphabet (especially for nouns) – and the trend was to use the No. 2 written form, capturing the more optimistic mood of the times.

While the written form of mangnyeon-hoe had changed in Chinese characters, when written in Hangeul, which was gradually replacing Chinese characters in newspapers and elsewhere, form No. 1 and form No. 2 were pronounced the same. This made it difficult to dispel the negative connotation connected to mangnyeon-hoe No. 1. This situation initiated another name change, again changing only the first character of this year-end affair. Mang was changed to song (see No. 3), newly naming the long-established event as songnyeon-hoe (송년회). This new label, literally meaning “send-off-the-year meet,” no longer carried the negative connotation or the original denotation of mangnyeon-hoe, and better represented the more sanguine times Korea was experiencing as it began its metamorphosis into an advanced nation.

As the new millennium rolled in, so did some new terminology: yeongshin-hoe (영신회, “welcome-the-new-year meet”). This term, however, lacked the staying power of any of its predecessors, losing out to its firmly established predecessor, songnyeon-hoe. A variant of yeongshin-hoe does live on, though, in the term for the early morning Christian worship service on the first day of the new year: yeongshin-yebae (영신예배).

Another recent attempt at changing the event’s name has also been undertaken due to the problem arising from the way in which some year-end party participants consume alcohol. At some of these get-togethers, the attendees take pride in downing strong drink. As a starter, they gulp down what is called poktan-ju (폭탄주, “bomb-drink,” i.e., a bomb shot or depth charge), a glass of beer with a shot of soju, or whiskey, added. In turns, everyone at the drinking table is often required to scarf down their “bomb.” The atmosphere is such that no one can resist. Some males fear that their failure to comply would put their manhood into question. A few rounds of drinking these “bombs” is enough to make the party-goers intoxicated. After the party, it is common to proceed to a nearby norae-bang (노래방), a karaoke singing room, to vent any and all pent-up frustrations or express their joys by singing loudly to give the culminating year a thunderous send-off.

Considering the aftermath of such drinking bouts, it is said that a law enforcement officer introduced a quite novel term for the year-end occurrences (No. 5), which is pronounced the same as Nos. 1 and 2 (mangnyeon-hoe) but has Chinese characters that give it the meaning “spoil/ruin-the-year meet.” He warned against drinking excessively during this festive time of the year even though it was not customary to leave drink out of the jovial occasion. According to him, out of the annual traffic accidents caused by drinking, the accident rate at the end of the year and at the beginning of the new year was the highest. Statistics issued by the Traffic Security Administration bore this out. Although the Gwangju area marked the lowest traffic accident rate among the major cities in 2004, out of the total traffic accidents of 220,755 in Korea that year, 25,150 (11.4%) cases were caused by drunken diving. Out of these, fatal cases were 875, comprising 13.3% of the total traffic deaths of 6,563 for the year. Korea had notoriously been a world leader in traffic deaths. [In recent years, however, Korea’s traffic deaths have dropped significantly, falling to 3,349 in 2019.]

The law enforcement officer disclosed his anguish in having to deal with traffic accidents and the suffering they caused. He had a philosophy of his own, saying that punishment alone was not a sufficient remedy to the problem. Along with strict enforcement of the traffic laws related to drinking and driving, the officer suggested a measure that would permanently reflect the offender’s evolvement in a traffic accident (similar to the registering of sex offenders in the U.S.). After all, one should be aware of the dangers of falling into the temptation of driving under the influence and thinking that one will manage to avoid any police checks. Irresponsible drinking and driving in connection with year-end parties can turn the jubilant event into a mangnyeon-hoe in the ruinous sense of No. 5!

Over the years, as more and more people have become car owners, the amounts and frequency that car owners drink appears to have been decreasing. After drinking, the responsible car owner may leave their car in the parking lot and take a taxi home. Or they may call a driver service to come and drive the car, and its owner with a high blood alcohol level, home safely.

May your songnyeon-hoe this year be a responsible and a safe one.

Original article written by Shin Sang-soon.

Adapted from the original by David Shaffer.