Behind the Myth: Are Koreans “Pure-Blooded”?

By Stephen Redeker

This series of articles sheds light on some Korean myths, folklore, traditions and superstitions. Every country has their own share of beliefs, fact or fiction, and many foreigners living in Korea have not yet heard or learned the basis for various Korean beliefs.

Pure Bloodlines

Most people love their country. You’ll hear many reasons why people think their country is the best in the world. Maybe it’s the delicious food. It could be the beautiful landscape and architecture. Perhaps it’s the friendly, good-looking people. Korea possesses such beliefs about its country as well.

There is a strong nationalist feeling among Koreans. One of these particular beliefs is about their heritage and ethnic identity. Some Koreans think that as a nation and as a race of people, they are a “pure-blooded” population – that Korea has descended from a unified group of ancestors with no racial mixing.

Scientific studies have revealed that the earliest settlers on the Korean peninsula may have arrived some 500,000 years ago. Subsequent migrations have come from the Siberian plains, then from Mongolia and through the Manchurian area of eastern China. DNA sample studies also show strong similarities in the genetic traits of southern Koreans and the Japanese.

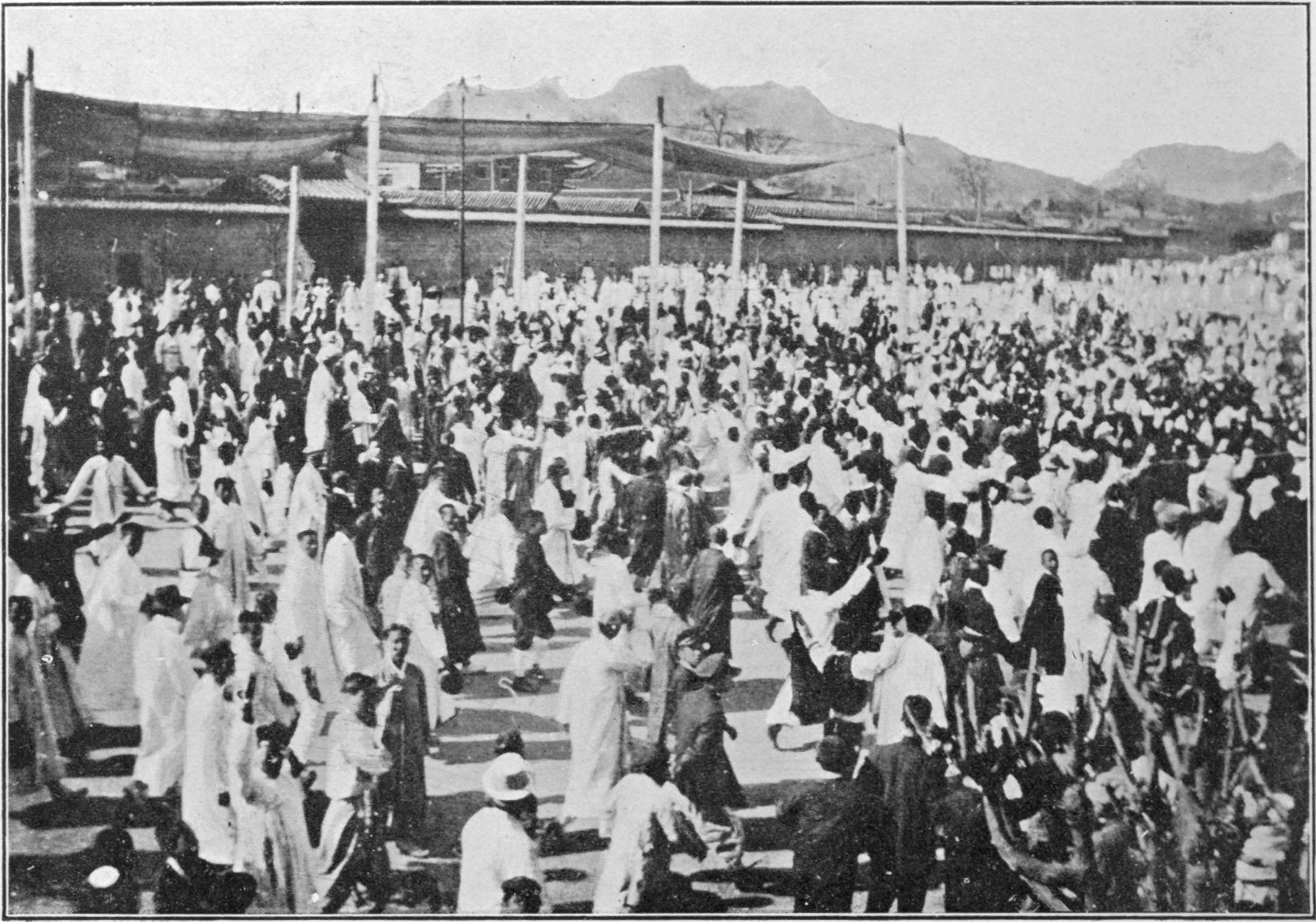

To truly understand this Korean myth, you have to recall the more recent history of just this past century. In the very early 20th century, the “pure bloodline” belief came about when historian Shin Chae-ho wrote of the Korean minjok (민족), which he described as a group of warriors who fought off invaders in order to preserve the Korean ethnic identity. He claimed that since the minjok movement had declined, it was necessary to reinvigorate its cause, especially in light of Japanese colonization and assimilation at that time. This belief encouraged the Korean people to resist Japanese rule and remain united during a time of serious national crisis.

Despite the fact that beliefs in racial purity declined after the World War II defeat of Germany and Japan, Korea (both North and South) kept on teaching the idea. As time passed, the “pure bloodline” myth remained steadfast ideology. It was used in political campaigns by former presidents Syngman Rhee and Park Chung-hee to demand people’s support and propagate an anti-Communist agenda. Meanwhile, North Korean propaganda declared Koreans “the cleanest race”. The belief continues on today and helps shape both countries’ political and foreign relations. It provides many Koreans with one more reason for national pride, and it further fuels hope for a reunified Korea.

But times are changing and Koreans are being forced to re-assess their belief in the racial purity of their heritage. Korea is increasingly becoming more multi-cultural as more foreign workers and international couples are calling Korea their home. Recently the multiculturalism of Korea was highly publicized by Hines Ward, American football player and Superbowl MVP. Ward’s father is African-American and his mother is Korean. After travelling to Korea, he preached acceptance of mixed-raced children and donated $1 million to found the Hines Ward Helping Hands Foundation, which helps mixed-race children in Korea.

Not all Koreans seem keen to accept an international and multi-cultural presence in their homeland. Many migrant workers and other immigrants still face discrimination and prejudice. Xenophobic concern rises when foreigners (including United Nations committees) attempt to refute claims of racial purity. Some Koreans believe a challenge to this national belief may dilute the strong national pride of the people and weaken the desire for Korean reunification.

All things considered, believing in the purity of their blood was important for Korean ideology during the past century, given the many challenges that Koreans faced. Maintaining a sense of nationalistic pride was essential during the time of invasion by forces threatening the well-being and culture of Korea.

In the modern era, Korea’s challenge is dealing with the increasing number of multi-cultural families living here, as more and more Koreans build families with partners from foreign nations. The number of people moving to Korea and raising multi-cultural children here is continually increasing as well. In fact, roughly 15% of children born in Korea are from a mixed marriage.

Love and acceptance for these “non-Koreans” living in Korea is something that will hopefully become a widespread reality. If so, that will strengthen the Korean nation, both in the eyes of its people and in the rest of the world.

Sources: Gi-Wook Shin, Ethnic Nationalism in Korea: Genealogy, Politics, and Legacy (Stanford University Press, 2006); Hyung-il Pai, Constructing “Korean” Origins (2000), p. 6; Shin Hae-in – The Korea Herald, 3 August 2006; Atlas Korean History – Sakyejul Publishing Inc.

Thank you for this post.

Did you found out what school books say about the Korean History? I wonder if they still protect this ideology by non-mentioning that they have Manchu, Japanese, Chinese or Mongolian blood?

Invasion is a sensitive topic there but I’d be curious to find out what scholars/books deliver.

Hi Laura. Thanks for your comment. Here’s Stephen’s (the author) reply:

“I don’t know what the current textbooks say about this topic. I agree it is a sensitive issue with Koreans, but most of us (in one way or another) descended from a mixed population, as history shows that people have migrated from one region to another all over the earth. Invasions have also caused races and cultures to mix, as you’ve mentioned. I will ask current Korean students if they recall what their textbooks say about it. Thanks for reading!”