Leap Month in a Leap Year

Original article by Shin Sang-soon.

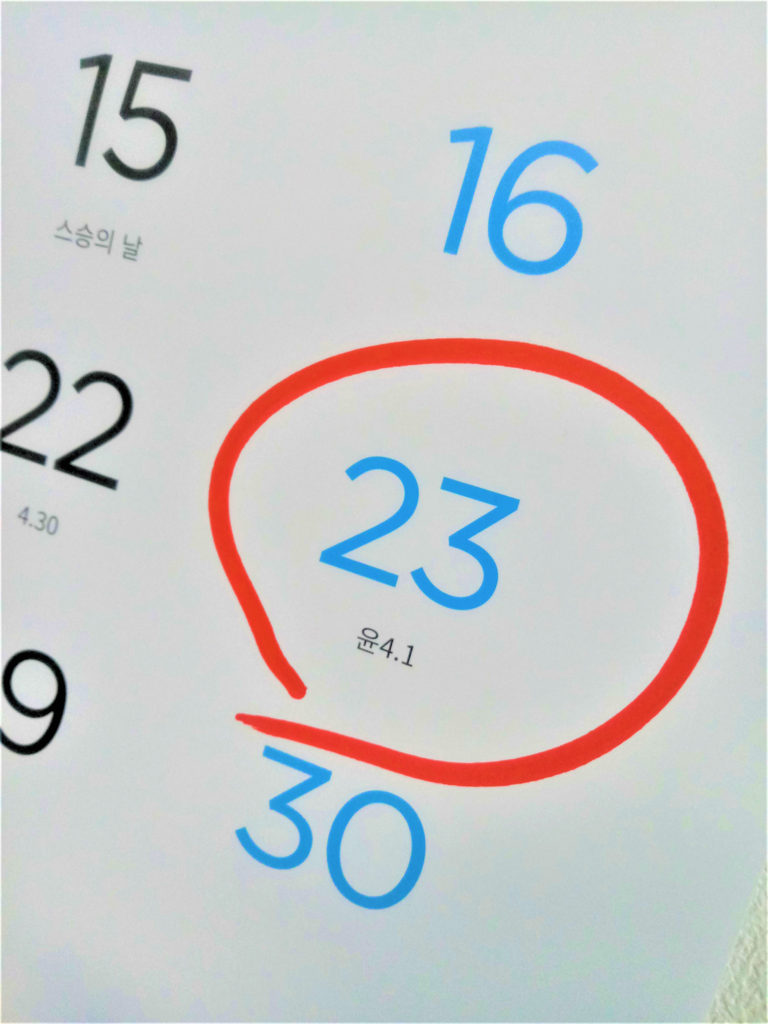

Supplemented by David Shaffer.

If you take a look at your 2020 made-in-Korea calendar, you will see that this year is a leap year. And if you look closely, you will likely also discover that most of the month of June falls within a “leap month” this year – a 29-day additional 4th lunar month falling between May 23 and June 20. Accordingly, this month’s “Blast from the Past” article features much of an article originally appearing in the October 2006 issue of the Gwangju News, “The Way Koreans Are Obsessed with a Leap Month,” written by Prof. Shin Sang-soon (1922–2011) and now amply supplemented with additional material. — Ed.

The solar calendar has a leap year; every fourth year, February has 29 days, as it does this year, instead of its standard 28. It is usually the custom for a man to ask a woman to marry him, but in a leap year, and especially on February 29, it is the custom that a woman can ask a man to marry her, according to Irish and British tradition. In the Western world, babies born on February 29 have been considered to be creative, having a “sixth sense”; being born on a leap day was considered lucky. This suggests that the solar leap year, especially February 29, is looked forward to by many a woman. In this sense, the leap year in Western culture can be regarded as an auspicious time.

Korea has used the lunar calendar for a long, long time. It was only from the time of the 1894 Gabo Reforms that Korea started using the solar calendar. The lunar calendar “year” was one of twelve cyclically recurring terms indicated by two Chinese characters that were a combination of the 10 heavenly stems and the 12 earthly branches, which combined linearly into 60 combinations [see Gwangju News, January 2020, pp. 8–10 for details]. So, the same combination of year names, for example, gapja (갑자), recurs every 60 years. This is why the all-important 60th birthday is called hwangap (환갑, “the return of the beginning”). In a long history like that of Korea’s, indication of the year by one of only twelve terms makes for much confusion. So, in recording historical events, the reigning king’s name was attached to the cyclical year name (e.g., Sejong-gapja, 세종갑자, “the year gapja during the reign of King Sejong”). As an aside, Japan also started using the solar calendar from the time of the 1868 Meiji Restoration.

Obsession with a Leap Month

Rather than having an extra day every so many years, the Korean lunar calendar (which is actually a lunisolar calendar) has an extra month added every so many years. The lunar leap month (yuntal, 윤달) has a special meaning for Koreans. Even though it has now been over a century since Korea adopted the solar calendar, the lunar calendar still occupies an important position in Korean life, especially in agriculture and fishery. The 24 seasonal divisions (jeolgi, 절기) of the lunar calendar are thought of as the proper times for ploughing, seeding, drawing water into rice paddies, weeding, harvesting, and so forth on land and for closely watching the rise and fall of the tide at sea, all necessary for good harvests.

The lunar leap month, or intercalary month, occurs 3 times in 8 years and 7 times in 19 years to keep the lunar calendar in rough agreement with the seasons, coordinating the seasonal difference between the solar and lunar calendars that arises from the earth’s revolution around the sun (365.24 days) and the moon’s rotation (29.53 days from one new moon to the next). The fraction of 0.24 of a day adds up to make almost a full day in four years, hence, one extra day in February, and the fraction of 0.53 of a day in the lunar rotation results in the alternating occurrence of 29-day and 30-day lunar months, which are still indicated on many Korean calendars.

Korea’s ancestors believed that the heavenly and earthly gods controlled a myriad of phenomena occurring on the earth for the entire twelve months of the lunar-calendar year. As the leap month was not considered to be an ordinary month, it was believed that many normally restricted activities could escape the wrath of the gods when done in a leap month. In this way, people felt released from the ordinary prohibitions of their farming and fishing communities. As there was thought to be an absence of impurity and misfortune from a leap month, this was deemed to be a good time to carry out activities such as house repair, moving, marriage, childbirth, gravesite moving and maintenance, and the making of funeral clothes.

The following account is from the Dongguk-sesigi (동국 세시기, Record of Seasonal Customs of the Eastern Country), written by the Confucian scholar Ha Seok-mo around 1850 and depicting traditional customs and folklore.

According to custom, it is good to marry and make funeral clothing during a leap month. Nothing is prohibited. Every leap month, women from the capital city of Seoul come to pray and leave money on the stone pagoda at Bong-eun Temple near Gwangju [now part of Seoul’s Gangnam District], a practice that continues until the end of the month. As it is said that by doing this, one can enter Paradise, the elderly from everywhere rush to the temple. Other temples in Seoul and the provinces have the same custom.

The Tang Saju (당사주, Divination of Tang China), a book adopted from China, contained no mention of a leap month, but somehow the passage stating that “the good is apt to be accompanied by the evil and the evil by the good” crept into Korean leap-month thought and now Koreans generally avoid marriage and childbirth during a lunar leap month. Because of this unfounded idea, there occur many tragi-comedies in present day Korea, such as avoidance of child delivery or marriage during a leap month. An expectant mother tries to avoid delivery during a leap month for fear that the child will seldom be able to celebrate their birthday anniversary – because “only god knows” when the same leap month will come round. So, expectant mothers may undergo Caesarian operations before a leap month. Couples also shun away from a leap month marriage date for fear of few wedding anniversaries to observe. On the other hand, things like house moving, reburial of ancestral graves, and the making of garments for the dead (su-ui, 수의) were recommended. The making the death garments while the parents were still alive was to be done during the leap month because death garments are also interpreted as “longevity clothes” (from the Chinese characters for the word) guaranteeing the parents’ long life when made during a leap month.

Be that as it may, there is one remedy for the fears that still surround the lunar leap month in regards to childbirth and marriage. That is doing away with the lunar calendar and its superstitions, and sticking to the solar calendar! But remember, the old ways die hard!

Leap Month Taboos

Old ways do indeed die hard, especially in fishing communities. Though many prohibitions during regular months were acceptable during a leap month, there remained some taboos that were not. With time, the following have disappeared from the folklore of much of the peninsula, but remained best preserved on Jeju Island.

- Sifting grain towards the door of the porch will ruin the household.

The guardian deity Munjeon-sin resided in front of the door of the house. Therefore, sifting grain in that direction was considered as being the same as driving the deity from the house.

- Raising a fence in the back of a house in which one has been living for a long time will result in a loss.

The fence-building taboo did not apply to a newly built house, but if a long-standing house were to have a fence built in the back, it was thought that the wealth and prosperity of the family would be lost.

- The gate of the house should not face in an arbitrary direction.

The direction of the gate of a house was to be chosen with great care. If the direction of the entrance was not chosen in accordance with the year, month, day, and time of birth of the house owner, the gate god would not protect the owner from disease or bring prosperity to the household.

- Filling in a well would turn a person mute.

The water spirit, Yonggung, was thought to dwell in wells. If a still-functioning well were to be filled in, it was believed that this would anger the spirit so much that the one who filled in the well would become mute.

- Fires should not be made with fruit tree kindling.

Kindling fires with wood gathered from fruit trees was thought to cause the fruit trees in the vicinity to no longer bear fruit – and for misfortune to befall the government!

- Receiving scissors without paying for them brings misfortune.

The scissors’ function of “cutting things in two” was construed as bringing misfortune. Acquiring brooms without payment in some form, likewise, was though to bring misfortune to the household because brooms “sweep things away.”

- A newly built bridge should not be first crossed by a young person.

It was believed that if a young person was the first to cross a newly constructed bridge, the water spirit would cast a curse on the child, causing death within three years.

- Sewing should not be done when the village is in mourning.

Sewing was equated with making one’s own funeral garb. It was believed that the spirit of the house would report the misconduct to Yeomna-daewang, the king and judge of death and the dead, causing harm to befall the offender. It is easy to cast off leap month-related beliefs in Korea as a thing of the past; however, in doing so, how would one explain that in recent years Korea’s cremation facilities are fully booked during a leap month, with many of the bookings being for the cremation of buried corpses? And in addition, in order to lure customers during a leap month, wedding facilities offering up to 50 percent discounts can still be found. Yes, old ways certainly do die hard.