The Legends of Yi Sun-shin and His Turtle Ships

Anyone who has been in contact with Korean history for a day has become aware that Admiral Yi Sun-shin is considered to be Korea’s preeminent military hero and his “turtle ships” are considered to be the world’s first iron-clad ships. We know that legends have a tendency to grow with time: Did George Washington really chop his dad’s cherry tree with a new hatchet, or did his biographer, Mason Locke Weems, create the story for the fifth edition of his biography of Washington? Similarly, how much of the legend of Admiral Yi and his legendary turtle ships is based on fact? Andrew Volle addressed this in two past issues of the Gwangju News’ Behind the Myth column: “Admiral Yi Sun-shin” (October 2013) and “The Turtle Ship” (January 2014). — Ed.

Admiral Yi Sun-shin: Truth or Myth?

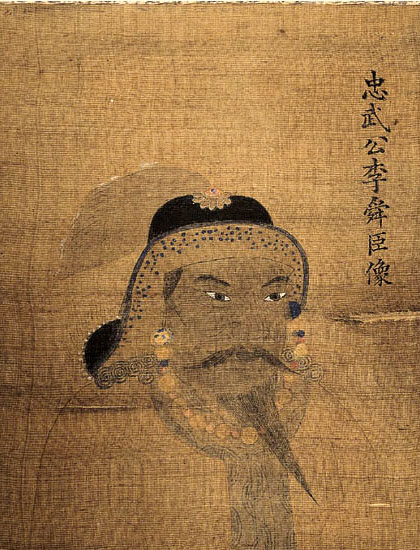

Admiral Yi Sun-shin (이순신) is Korea’s greatest example of heroism, but how much of his story is true? Without a doubt, his military accomplishments were real. As a commander of Korea’s navy during the Imjin War, the admiral won all 23 naval battles he fought from 1592 to 1598. Even his amazing victory at the Battle of Myeongnyang (명량, island off the coast Jindo Island), in which his 13 ships defeated 133 Japanese ships in 1597, is not questioned by historians. The man was a strategic genius.

For his great contribution to winning the war that took his life, kings and scholars honored Admiral Yi for hundreds of years, but nobody considered him the perfect Korean. (Indeed, a superior officer once falsely charged Yi with desertion in battle, for which Yi was imprisoned and tortured.) After Japan finally took control of Korea in 1895, however, the impression of Yi began to change. Writers thought the people needed a good example to teach them how to fight off Japan. What better person could they choose than Yi, who helped save Korea from the last Japanese attacks?

The writers made Yi more than just a war hero though. In The History of Joseon (조선상고사), Shin Chae-ho (신채호) told readers that Yi was “both a hero and a saint” sent by God. Later, Lee Gwang-su (이광수) wrote the long-running newspaper novel, “Yi Sun-shin,” to establish the admiral’s moral excellence. In the novel, Yi is almost a Korean Christ: a perfect but persecuted man who dies saving his stupid, evil people from themselves.

Yi continued to be elevated after Japan’s WWII defeat in 1945. South Korea especially encouraged people to admire Yi during the military rule of President Park Chung-hee from 1963 to 1979. As a war hero, Yi was a great symbol for the army-controlled government.

All this propaganda had the effect of greatly improving the drama of Yi’s story. In life, Yi sometimes filed exaggerated or false reports to the king, hoping to improve his name at the royal court. Today, Yi is known as a man motivated only by love for his country and men, and any men who became angry at Yi’s behavior are remembered as jealous, lying fools. People also think Yi was a genius at building ships, not only fighting with them; he is popularly (but wrongly) believed to have designed the world’s first war ship with iron armor: the turtle ship.

The most dramatic change to Yi’s story is the idea that Yi chose to die in his final battle. Some say Yi preferred death than to be treated badly again by an unappreciative king, so he took off his armor. Others say he wanted to inspire his men, so he stood at his boat’s front. Everyone agrees that as he died, Yi asked for his death to remain secret until after the battle.

The truth is, he might have. That is why historians need to rediscover the real Yi Sun-shin: He was neither the Buddha or a Genghis Khan, but behind Yi’s myth is a man worth knowing.

The Ironclad Turtle Ship: Fact or Fiction

Did Korea really invent the first ship with iron armor?

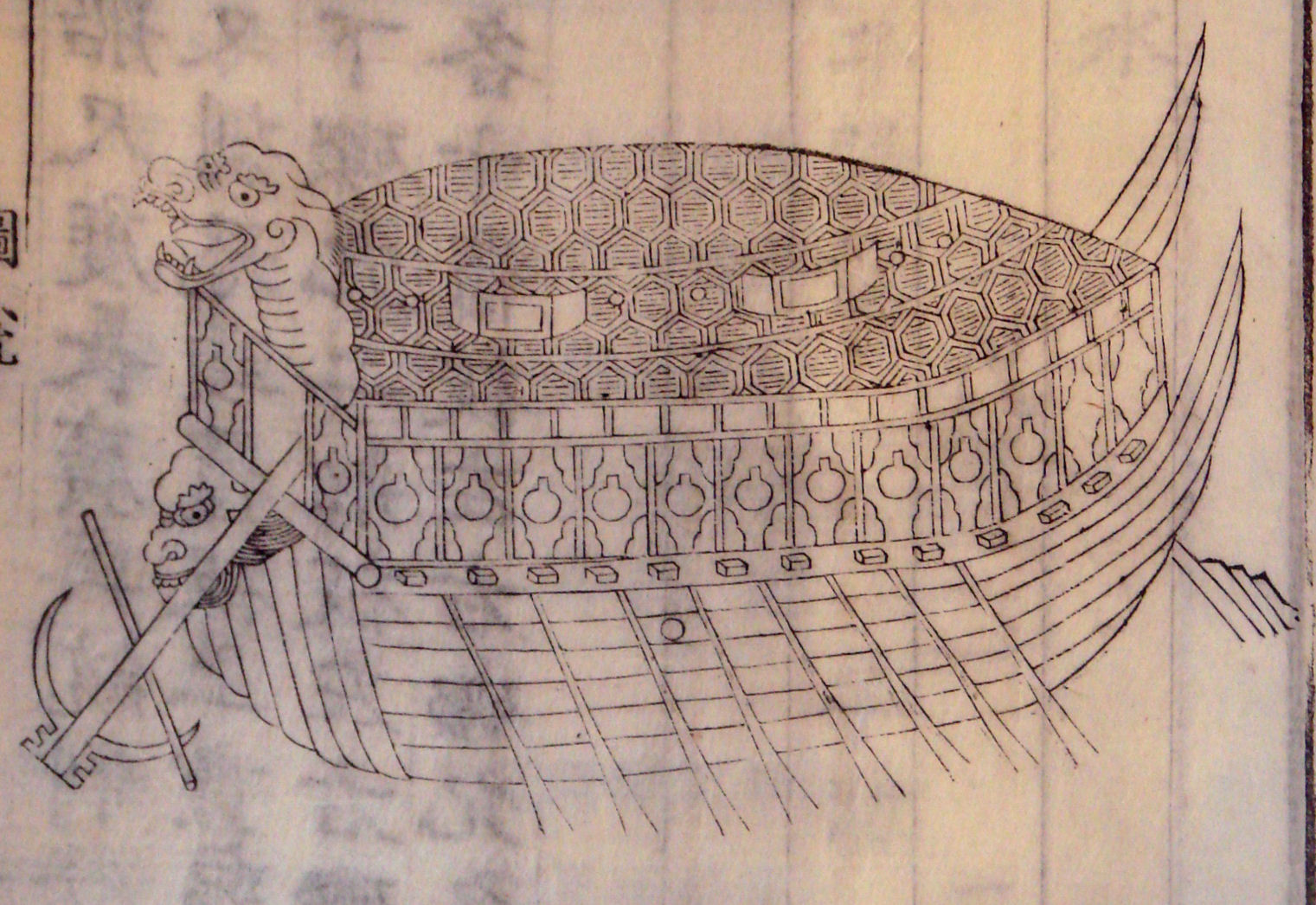

The question should be asked with sensitivity because of the national pride at risk in the answer. In particular, South Jeolla Province and its port town of Yeosu have long celebrated their status as the home of the geobuk-seon (거북선, turtle-ship), a warship supposedly protected from Japanese projectiles and boarding parties by an iron roof covered in spikes, said to be the first historical use of iron armor in naval warfare.

The turtle ship’s role in Korea’s national mythology is even more important than its role in world history. The ship gets a lot of attention in Korean retellings of the Imjin War, multiple invasions from Japan (1592–1598), which now symbolizes every war. Its creation and use suggests that Korea can compensate for its small size through ingenuity.

Nevertheless, evidence strongly supports the theory that the turtle ships designed in 1592 had only wooden roofs with iron spikes. In his book Yi Chungmugong Haeng-nok (이충무공행록), Yi Bun, nephew to the famous Admiral Yi Sun-shin, described the vessels in detail, explaining that “the turtle’s ‘back’ is a roof made with planks.” The prime minister of Joseon at that time, Yu Seong-nyong (류성룡), also reported that the ships were “covered by wooden planks on top.”

Contradictory evidence is almost nonexistent. Scholars find no mention of plated ships in any Korean writing from the era. Even Admiral Yi Sun-shin, who ordered the construction of the ships, wrote nothing of the idea in his journal, possibly because he realized that putting iron plates on the ships would have been a bad idea. The ships did not need the additional armor; thick wood was enough protection, since the Japanese used few cannons at sea. Moreover, cladding the ships in iron would have slowed them down. Since turtle ships were meant to ram other vessels, their speed was very important. Finally, there was the expense: The iron needed to armor a single geobuk-seon equaled the cost of another geobuk-seon.

But even if the vessel’s architect, Na Dae-yong, did not cover his creations with metal, he still designed a ship worthy of Korean pride. (By the way, Na Dae-yong was a government official who resigned his post in 1587 to return to his hometown of Naju, South Jeolla Province, to devote himself to designing the geobuk-seon.) The geobuk-seon represented a multitude of advancements in shipbuilding. Ironically, one of these advances was the use of wooden nails (pins) instead of metal ones. Metal nails rusted, weakening the ship, but the wooden pins absorbed water and expanded in their holes, which strengthened the ships’ joints. More visibly, the ships became capable of shooting cannonballs directly fore and aft, a new maneuver that the sailors used to brutal advantage; they rammed enemy ships, then fired cannonballs at them at nearly point-blank range.

For now, however, the iron roof remains the mistaken focus of praise for the famed turtle ship.

Written by Andrew Volle.

Compiled by David Shaffer.

Sources

신채호. (1931). 조선상고사. Seoul: 조선사연구초.

이과수. (1930, June 26 – 1932, April 3). 이순신. Seoul: Dong-A Ilbo.

이분. (1613). 이충무공행록. Joseon.