Gwangju, Creating a Personal-Mobility Green Transportation City

By Chung Hyun-hwa

The Lost Bike Town

When I was a first-grader, I was living in Namwon. There was something really interesting about Namwon: It was a bike town. Everyone rode a bike, whether young or old, male or female. Some bikes with wide rectangular carriers behind the seat were used to carry heavy things such as big rice bags. A lot of bikes had baskets in the front to carry the stuff bought at the market. My mom would even carry me on the carrier. People did not wear padded pants or helmets because bikes were just transportation. Namwon did not have public buses or cars but did have a few taxies; however, it had a clean stream flowing across the town, where children went to catch fish or little shrimp. There was the cloud-like Milky Way as well as big stars dangling in the night sky. The streets were dark, and there were fairy-like fireflies floating in the summer breeze. There were rainbows after rains, sometimes two at the same time. Thinking back, it was the kind of town I would like to live in again; most crucially for this article, people rode bikes.

Gwangju: A Green Transportation City

Gwangju set up a plan to be carbon net-zero by 2045, but how? Mr. Jang Hwa-seon, the director of the Gwangju Namgu District Town Community Center who has been a strong advocate of personal-mobility green transportation all his life, believes that going green on transportation is a good starting point to reduce carbon emissions. Nationally speaking, the industrial sector releases the most carbon, but a city like Gwangju does not have as many factories, so transportation makes up the biggest portion of carbon release. According to the 2019 Gwangju Greenhouse Gas Inventory Research Report, published by the International Climate and Environment Center (ICEC, 2021), 92 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions was produced by the energy sector from 2005 to 2017 in Gwangju. Out of the total greenhouse gas produced by the energy sector, about 32 percent was from transportation, while homes, the commercial sector, and the industrial sector produced about 20 percent each.

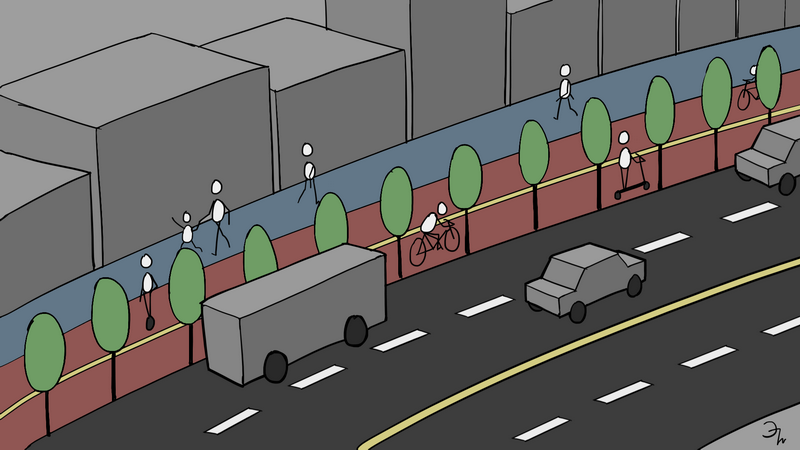

A lot of cars are carrying only one person most of the time. Personal transporters consume much less energy to serve the same purpose for sure. Now there are already many different kinds of personal transporters on the street: bikes and electric bikes, electric kickboards and onewheels, as well as electric wheelchairs, but there is no system to operate them safely. I especially feel sad to see electric wheelchairs run in car lanes. Therefore, I strongly urge that Gwangju’s government should start changing one-car lanes into a two-way personal transporter road system to help the city reach its goal of being carbon neutral by 2045.

Some people worry about the amount of car traffic if the number of lanes are reduced, but if more people use personal transporters to cut down on car usage, it will be effective. At the moment, construction of the city’s second subway line is going on, and the drivers all know how to avoid the traffic jams resulting from this project. Therefore, this is the best time to institute a personal transporter road system, especially when the first part of the new subway line is completed in 2023. An average bike can travel at 12–20 km/hr, and the rough diameter of Gwangju city is only 15 km, so theoretically speaking, you can go anywhere in the city within one hour by bike. If you are not living at one extreme end, and if you are not going to the other extreme end, you may be able to get to most places within 20 to 30 minutes. If you ride an electric bike, this will cut down the time to half because they guarantee the same speed all the way, and you do not need to ride around in circles to find a parking spot. Health benefits are also a plus.

The Obstacles and the Solutions

- Riding a bike is dangerous and inefficient because of cars, bumps, and people. – If I go downtown on my bike, it is only 1.6 km. According to Naver Map, it takes seven minutes, but in reality, it takes longer because of illegally parked cars blocking the bike path, which make me get off my bike. There are bumps on and off the bike path along the sidewalk, and there are always people to be careful of. The bike path on the sidewalk sometimes disappears, so you have to go into traffic lanes. The law has changed lately for bike riders to cross the road with pedestrians instead of moving with the traffic signals. It is safer this way. In the Netherlands, where there are more bikes than people, there are different signals for cars, bikes, and people, and they all take turns. If we want to encourage personal transporters to cut down on car use, it should be safe, fast, and convenient. It is better for drivers and pedestrians as well.

- Riding a bike is not healthy because of the fumes. – In countries such as the Netherlands, the U.K, and France, where bikes have become the major mode of transportation, there are tree zones between traffic lanes and bike lanes for safety and health reasons. The trees also provide shade that is great for bike riders. (Another idea for shade is to install a structure to put solar panels on top, so this would serve as separating walls and as shade that would protect the riders from strong sunshine and rain while producing electricity for the city.) Also, the number of cars would decrease if there were fewer car lanes, and the portion of electric cars is set to increase rapidly, so the hazard of fumes will decrease also.

- Riding a bike limits our outfits, and helmets mess up our hair. – A lot of people do not want to ride bikes for transportation because of the helmet requirement. If we had independent personal transporter roads, the risks we would take would decrease tremendously, so helmets could be worn only by those riding at high speeds. Denmark and the Netherlands do not compel riders to wear helmets to promote riding. They ride bikes in their normal attire, even in skirts.

- Riding a bike is only for young people. – Because of the advent of electric bikes, physical strength is not an issue any more. There are also tricycles that are hard to fall from.

Time of International Collaboration

Recently, Daegu’s city government had a bike path conference, and the Dutch Embassy enthusiastically shared its learnings from their almost 50 years of bike culture. Because their land is below sea level, the Dutch know global warming actually threatens their lives, and they cannot stop this by themselves. Daegu is the hottest city in Korea due to its basin-like geographical features, so global warming is also a looming concern. Watching the conference on Zoom, I was encouraged by their internationally collaborative actions. I hope Gwangju’s city government will also take such actions.

Suggestions

Jang Hwa-seon has a few additional suggestions:

- Use the Ecobike public app, a potential big data source for the bike lane system in the future. This functions the same as ordinary bike apps, by tracing your trips and including your bio information as well.

- A campaign to make bike riding in the city safer should start as such: Automobile drivers and pedestrians should respect the current bike lanes so that riders can travel faster and more safely. Drivers should not park their vehicles on sidewalks, illegally blocking bike lanes, and should not honk at bike riders on the street because it can scare the bike rider and put them in danger. Pedestrians should try to walk avoiding the bike lane on the sidewalk until there are independent paths for bikes.

- Gwangju’s city government should cover its citizens’ bike accident insurance, as in Daejeon, Chuncheon, Namwon, Sejong, Goyang, Anyang, Jeongeup, and many districts in Seoul. In Gwangju, Gwangsan-gu is the only district that is insuring all its bike riders.

- Gwangju’s city government should try to connect the bike lane system with the two subway lines and the public bus system so that bike riders and bikes can be accommodated in the transfer to public transportation.

The Vision

The family vehicle culture started in the 1990s in Korea, and bikes have become a means of exercise more than transportation. However, it is high time things change again: Bikes should come back as a transportation weapon to fight against the climate crisis. The vision here is that Gwangju can be reborn as a real ecological city that everybody wants to visit or live in. Gwangju once seemed somewhat far from the capital, but with the internet and fast train connections, now there is not much you cannot do because of location. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Gwangju has also proven to be one of the safest cities. More people who can work online will choose to live in Gwangju and enjoy the slower pace of life here: riding a bike in the city, going to the Yeongsan River for the wonderful scenery, going hiking in Mt. Mudeung, and enjoying the southern delicacies. The paradigm is changing, and Gwangju is going to take the initiative. Go, Gwangju!

Illustration by Wi Hun-ho.

Photographs provided by Jang Hwa-seon.

Reference

ICEC. (2021, July 6). (재)국제기후환경센터, 2019년 광주광역시온실가스 배출통계 및 배출특성 연구 보고서, 국제기후환경센터 홈페이지 자료실. http://icecgj.or.kr/Board/kr/0203/List#Down List33470cefec84ea2671b61903c1c00479

The Author

Chung Hyun-hwa is from Gwangju and is currently leading Gwangju Hikers, an international eco-hike group at the GIC, and getting ready to teach the Korean language. Previously, she taught English in different settings, including Yantai American School and Yantai Korean School in China, and has worked for the Jeju school administration at Branksome Hall Asia in recent years. She holds a master’s degree in TESOL from TCNJ in the U.S.