Mindful Diet: The Climate (and Food!) Crisis

By Chung Hyun-hwa

I have always known that some people insist on eating plant-based foods only – vegans. In Korea, for a while, Dr. Yi Sang-gu, an advocate of the vegan diet, was on TV frequently. His diet was about becoming healthier through not eating meat because humans are not designed to eat meat. However, his veganism was rooted in his religion, and people still liked eating meat, so slowly he disappeared from the media. The vegans I encounter these days have a different motivation for sticking to a plant-based diet: to fight against climate change. What? We have meat and climate crises?

The Food Distribution Issue

In June, I attended the online Kyunghyang Forum, Living with the Climate Crisis: The Path to Survival. Kyunghyang invited globally known lecturers such as Al Gore, Ban Kimun, Choi Jae-cheon, Jeremi Rifkin, David Wallace-Wells, and Michael Mann. It was a rare opportunity to listen to all of these well-known lecturers at one forum. Among them, Dr. Hope Jahren’s address on the current global food issue was very impressive.

According to Jahren’s book The Story of More, the world is producing three times more grain than in 1969 (when the author was born), even though the amount of arable land has increased only by 10 percent, thanks to agricultural technologies such as fertilizers, pesticides, and GMOs. The reality is that 40 percent of the grains produced on earth goes to people, another 40 percent is fed to animals, and the remaining 20 percent is used for biofuel. Meat production is the same. The total number of animals decreased, but the production has tripled since 1969. To get meat, 30 percent of the freshwater in the world is required, and two-thirds of all antibiotics in the U.S. are used for animals. This contaminates the soil and underground water. Animals consume one billion tons of grain, which is the same amount that humans consume, and they produce 100 million tons of meat and 300 million tons of manure.

The total population on the earth doubled to almost eight billion compared to 1969. At the moment, fortunately, the earth is producing enough food to provide 2,900 kcal per person aside from the grains used to feed animals, but unfortunately, 800 million people are suffering from malnutrition, while the animals to be used for meat are fed, and one-third of all the food in the world gets lost or wasted, according to UNEP. Thus, what matters is the distribution, not the food production itself. Jahren proposes that if the U.S. reduces its meat consumption by half, it could increase the food supply by 15 percent (because of less feed consumption by beef cattle and other meat-producing animals). If 36 OECD countries reduce their meat consumption by half, it would increase their food supply by 40 percent, or if they could have one “Meat-Free Day” a week, all the hungry people in the world would be able to eat for the whole year! She believes it is high time to get ready for when the population hits 10 billion in 2100, which is a conservative estimate.

Food and Carbon Issues

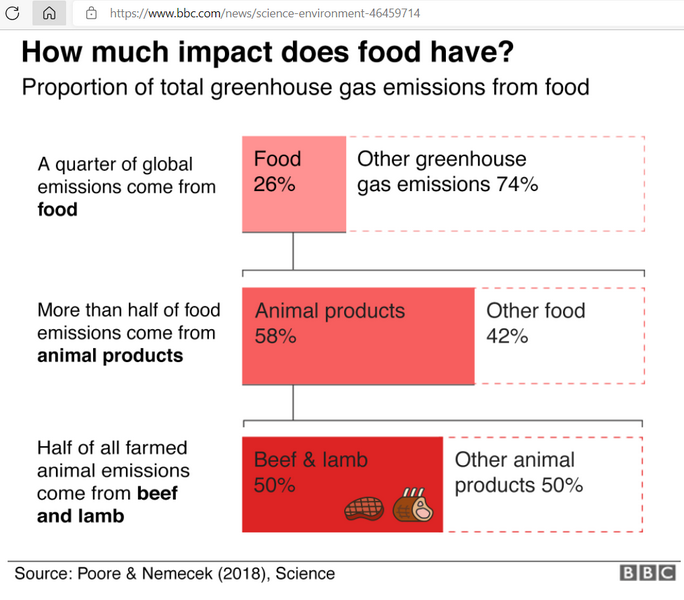

The table from BBC News shows the carbon impact of food. It is quite surprising to see a quarter of carbon emissions are from food, and more than half of those emissions are from animal products (15 percent). This is more than the impact of all forms of transportation combined, which is known to be 13 percent. Cattle and lambs are causing 7.5 percent of total carbon emission, equal to about half of transportation’s impact. Someone said, “Reducing meat can’t save us from the climate crisis, but we can’t be saved without reducing meat intake.” I thought this was well said.

In the U.K, the “Meat-Free Monday” movement was started by Paul McCartney in 2009, and it is spreading to other countries as well. They say that if you have one meat-free meal a week for a year, it has the same effect of planting 15 trees a year. So, I did some calculations to see if this was true. One kilogram of beef releases a minimum of 15 kg of carbon, and one serving is between 150–200 g, so this is 3 kg of carbon a serving. If you multiply 3 kg by 52 weeks, it is 156 kg of carbon saved a year. One tree that is 30 years old can absorb 6.6 kg of carbon a year, so if you divide 156 by 6.6, it is equal to the carbon absorption of 23 trees. Now, I am convinced that this number is not exaggerated. An ordinary person living an ordinary life will easily emit 8–10 kg of carbon a day, so one individual emits over 300 kg of carbon a year. Then, we need 450 trees a year to offset the carbon dioxide produced by a single person, so 15 trees for one meat-free meal is a big deal.

Meat Reduction Challenge

Meat has been part of the human diet for such a long time, so veganism almost sounds like a new religion to most of us. I think changing one’s diet is the most difficult action in the carbon-free movement. You could try to recycle better, ride a bike, or change your lifestyle to reduce electricity usage. You could do so many things, but changing your diet is not easy because your body is used to eating meat, and there is also social pressure when you gather with others. I was unsure if I could really do it myself, but by substituting meat with beans and nuts for several months, I concluded that it is possible to reduce meat to half without having much impact on the body. (My latest physical exam came out better than before.) The most difficult part of changing one’s diet to one that is plant-based could be hunger, but nuts that include good fat and oil will supply enough calories with good cholesterol that will support your vascular health. We need to study this a little more, but this would surely be a good challenge for the improvement of the environment and your body.

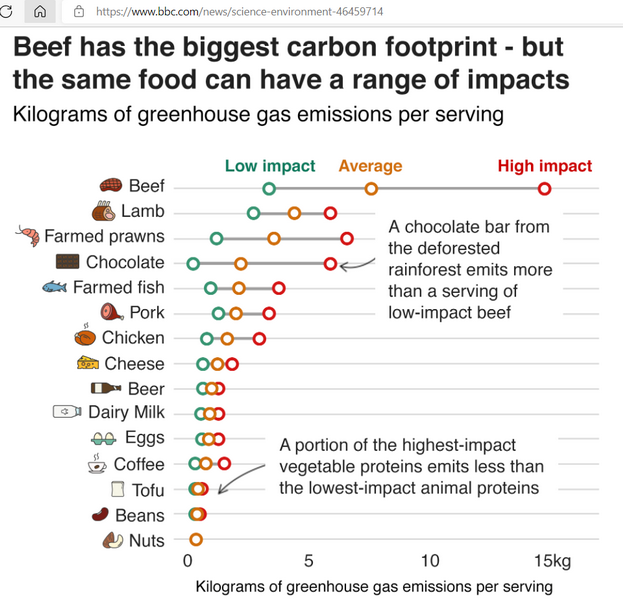

According to Jahren, the average American consumes 1,800 g of meat weekly (Koreans about 1,000 g a week). This is about 250 g a day. If we cut this in half, it would be 125 g a day, and I think that is something doable and even healthy. This means that you can include meat for one meal a day, and for the other two meals, nuts can be added to make up the calories. This will not starve you. Also, in terms of carbon emissions, cutting down on beef is the key. Seventy percent of the Amazon is being ruined to create cattle farms, and the farms grow feed for the cattle. Cattle there emit carbon, but the trees to absorb it are gone, so carbon emissions are doubled. One kilogram of beef emits 15 kg of carbon, while fish, pork, or chicken emit less than 5 kg. Thus, replacing beef with other meat is already meaningful. If you eat beans and nuts instead of beef, which produce less than 0.5 kg of carbon, it will make a big difference.

Conclusion

I hope there will be new technologies available to deal with the climate crisis in the near future, as technology develops at increasingly rapid speeds, but for now an IPCC report warns us that 1.5°C is the irreversible tipping point (we are just 0.4°C away at present), and we are now on course to reach that point by 2040 instead of 2050. Until we have technologies to save us, we will have to try to save ourselves. Having mindful meals each day is something we can definitely do right away with no extra investment.

Sources

Jahren, H. (2020). 나는 풍요로웠고, 지구는 달라졌다 [The story of more: How we got to climate change and where to go from here]. (E. Kim Trans.) Kimyuongsa. (Original work published 2020)

Worldwide food waste. (2021, October 8). United Nations Environment Programme. https://www.unep.org/thinkeatsave/get-informed/worldwide-food-waste

Stylianou, N., Guibourg, C., & Briggs, H. (2019, August 9). Climate change food calculator: What’s your diet’s carbon footprint? BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-46459714

The Author

Hyunhwa Chung is from Gwangju and currently leads Gwangju Hikers, an international eco-hike group at the GIC. She has started teaching the Korean language and working as a climate crisis advocate. Previously, she taught English in different settings, including Yantai American School and Yantai Korean School in China, Branksome Hall Asia, and in the Jeju school administration in recent years. She received her master’s degree in TESOL from TCNJ in the U.S.