The Devil You Know

Written by Jessica Keralis

Our natural tendency as human beings is to stick to what is familiar, even when it comes to the unpleasant. “Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t.” We move intuitively toward people and places that are familiar to us and invest in issues that impact us directly. I am no exception to this rule. Most of my advocacy work, including everything that I have published about HIV in this magazine, has focused on the mandatory testing policy for native English-speaking teachers that was passed in 2008 and finally lifted in July last year after a drawn-out battle through two UN treaty bodies and a steady drip of protests from the expat community. After all, my husband and I were subjected to the testing policy, so I had a direct connection. It was easy to write what I know.

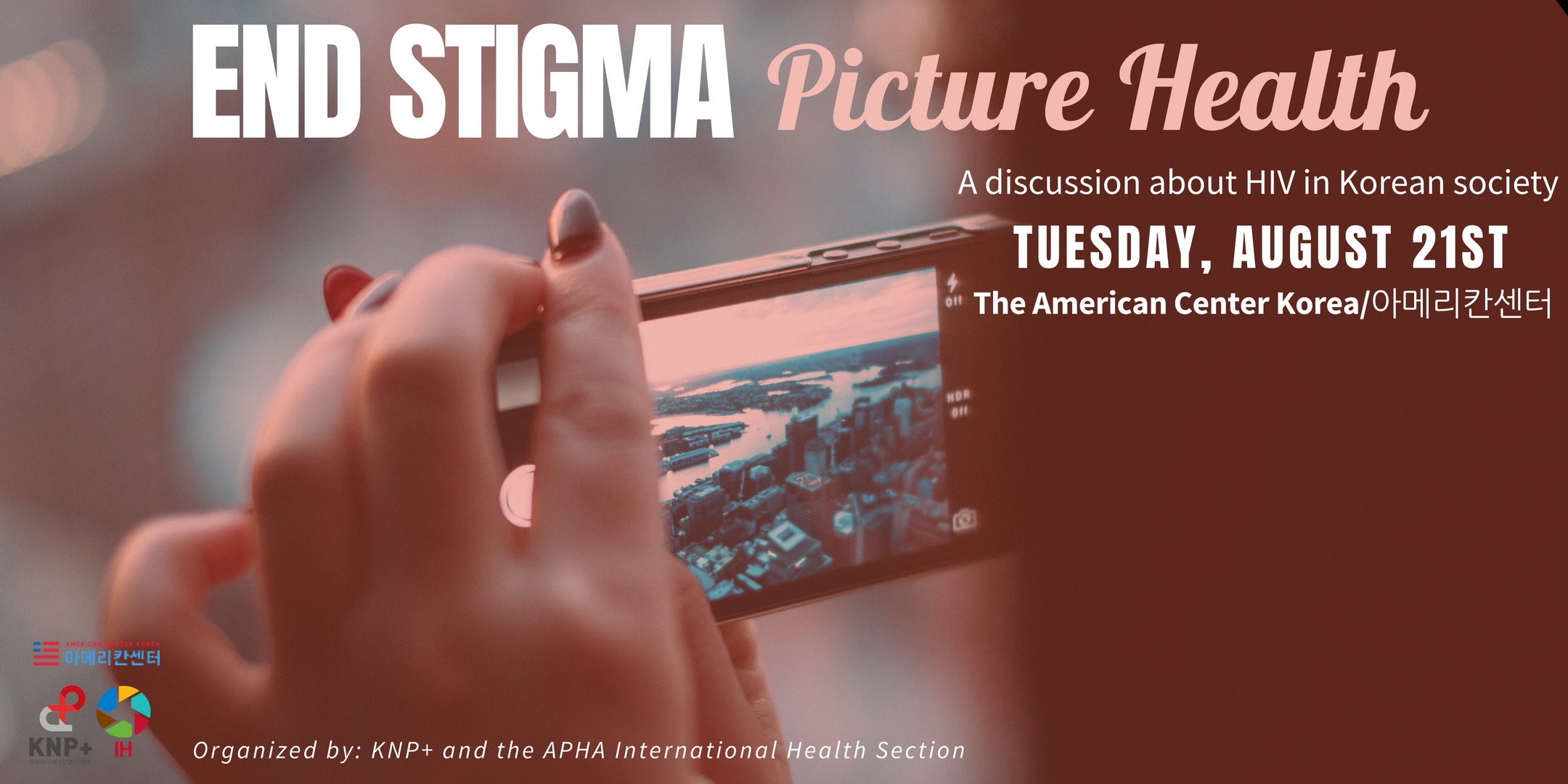

That all changed this summer. Through my professional society, the International Health Section of APHA, I worked with several advocacy groups under KNP+ (the Korean Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS) to organize “End Stigma, Picture Health: A Discussion about HIV in Korean Society,” a seminar on legal, social, and medical issues related to HIV on August 21. Hosted by the American Center Korea at the US Embassy in Seoul, the event featured speakers from a wide variety of backgrounds, including international human rights law experts, health sociologists and anthropologists, women’s rights advocates, and LGBT activists. Attendees learned about how stigma impacts access to medical care, the right to work, and the daily lives of Koreans living with HIV, as well as the ways in which stigma shapes attitudes and popular perceptions of the disease and those at risk.

It is those perceptions, and their accompanying misconceptions, that in turn drive much of the law and policy addressing HIV in South Korea. The widespread belief that HIV is a “foreigner’s disease” led in part to the HIV testing policy targeting foreign English teachers that lasted for nearly a decade and is the root of similar longstanding policies that still require testing for EPS workers and women on the E-6 “entertainment” visa. While the testing policy and its impact on foreigners have commanded much of the international media attention, Korean news stories are shaped by these attitudes as well. From the sensationalist coverage of the looming AIDS threat leading up to the 1988 Seoul Olympics to the “nationwide AIDS panic” sparked by the discovery last year of a sex worker in Busan living with HIV, the narrative of hysteria and demands that the contagion be controlled persist. After 40 years, not much has changed.

Though still infrequent, there is now a steady trickle of news stories coming out of Korea about the intense discrimination that people living with HIV face. After three years of (what sometimes felt like Sisyphean) advocacy work on this issue, the increased attention is encouraging. However, I still remind myself that such stories catch my eye because of my immersion in the topic. At this point, I suppose HIV-related stigma in Korean society is “the devil I know.” But that is not the case for everyone yet, which is why I am still writing articles and helping to organize a seminar nearly five years after my teaching experience in Gwangju came to a close.

Retired Australian Supreme Court Justice Michael Kirby first laid out the “HIV paradox” in 1996. He explained that the only way to control the spread of HIV was not to quarantine those most vulnerable to it, as our instincts might suggest, but to actively work to protect their right to health. Most countries learned this the hard way. Some are still learning, Korea included, as its number of new HIV diagnoses continues to increase each year at an alarming rate. This will not change until Korean society no longer views the virus as someone else’s problem. At the current trajectory, HIV will be the devil they get to know sooner than they realize.

The Author

Jessica Keralis lived and worked in Gwangju for nearly two years beginning in 2012. She is now a PhD student in epidemiology and has, through APHA’s International Health Section, worked on human rights advocacy related to HIV policy in South Korea since 2015. All views expressed here are her own and not those of any employer.