The Mental Burden on the Student

By Julien Laheurte

On May 24 this year, a 23-year-old international student at Chonnam National University in Gwangju took his own life on campus. The day before, he had been detained by police after riding his bicycle naked. Investigations revealed that the student was undergoing treatment for depression and struggling with academic pressure.

In response, international students organized a rally on May 27 to commemorate his death. They marched across campus, pausing at the engineering building where the student worked to observe a moment of silence. A petition was also signed, calling for “structural changes in mental health awareness at universities.”

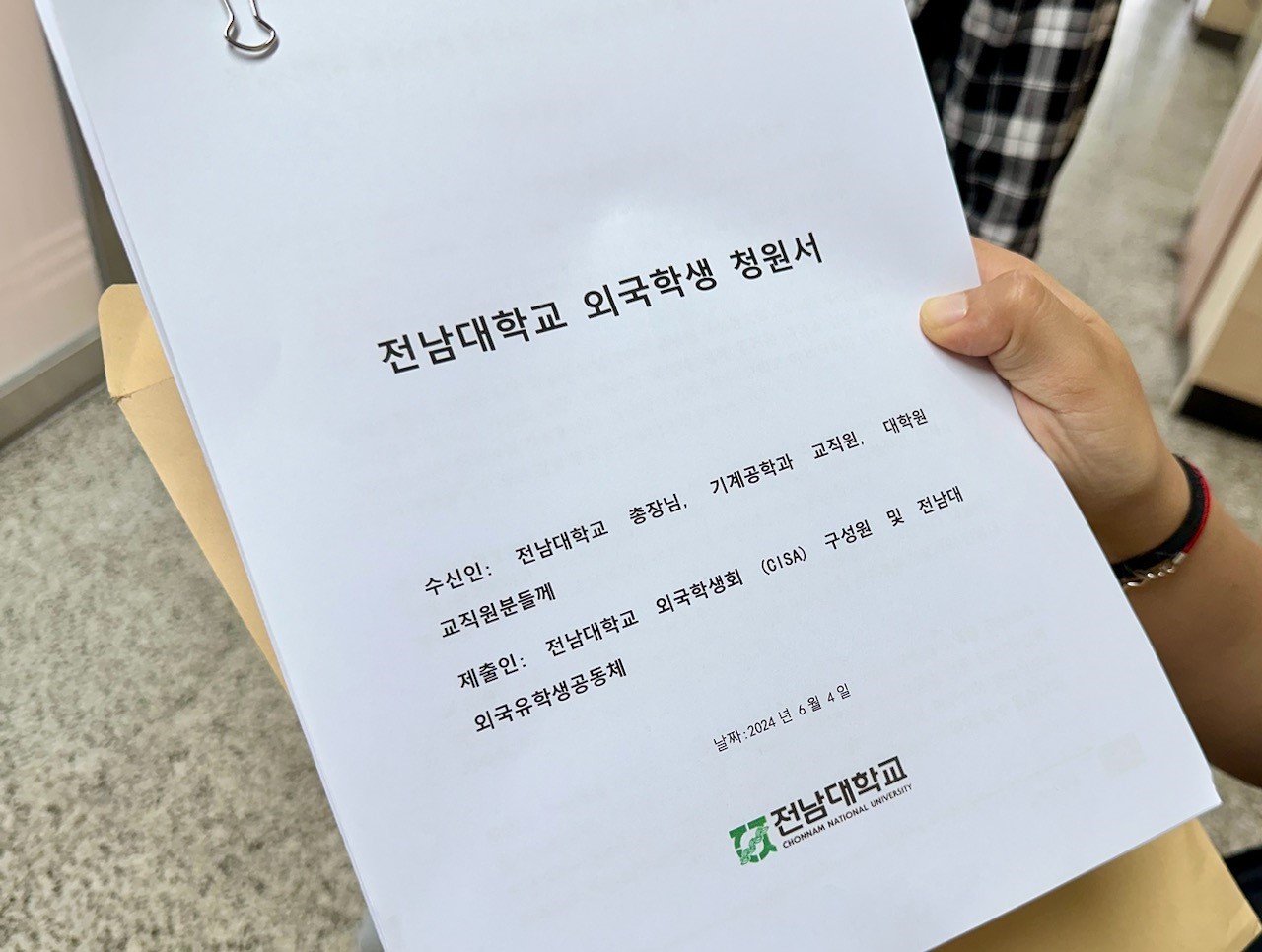

On June 4, the Chonnam National University International Student Association (CISA) submitted a more formal petition, signed by 276 students and local citizens. The petition was delivered to the student’s department, emphasizing that his death was not an isolated case but part of a larger issue within the Korean academic system. It urged the university to improve mental health support, particularly for international students who often face heightened risks of loneliness and social isolation.

This tragic case is not unique. Two years earlier, an Ethiopian international student in Seoul was found dead near the Han River after reportedly experiencing severe loneliness and isolation. Both incidents highlight a recurring and troubling pattern among international students in South Korea, pointing to a need for greater mental health support in academic institutions.

To better understand the challenges faced by international students and explore potential improvements in their mental health support, I interviewed Kim Dong-gyu, a South Korean freelance journalist who covered the Chonnam University rally, and an international PhD student currently at Chonnam.

Kim Dong-gyu, in his May 27 article for OhmyNews, highlighted two key points from his discussion with international students. First, he advocated for universities to establish “reliable, independent institutions” where students can safely report discrimination, bullying, excessive workloads, and human rights violations, providing a neutral space for students to speak freely without fear of judgment. Second, he cited a rally attendee who linked a student’s suicide to “extreme research pressure and harsh treatment” faced by international students and researchers (PhD students also being researchers), noting both intense competition and potential mistreatment. During my interview with Dong-gyu, I asked him to clarify the origins of those “harsh treatments.”

Dong-gyu explained that graduate students are viewed as “cheap labor” in Korea’s academic system, working long, often unconventional, hours for minimal pay. He attributed this to the “power dynamics within these institutions,” comparing it to the army. He further noted, “The hierarchical relationship between professors and students is well-defined, making it difficult to change the system.” Students must “navigate” this rigid hierarchy to earn their degrees and secure competitive jobs. In other words, they feel compelled to accept all tasks from their academic advisors to succeed, even when those tasks exceed their contractual duties or breach decency.

He added that students felt their fate depended too much on their interpersonal relation with their advisors, lacking a structure to “address and resolve any rights violations.” He cited the case of two Nigerian students who felt helpless, as their advisor was their only point of contact within the university. Additionally, some students feared speaking out, worried that conflicts with their advisor could lead to their visas being canceled. This doesn’t imply that advisors inherently exploit their students, but if they do, there is very little to prevent it.

During my conversation with the PhD student from Chonnam, we discussed claims of “harsh treatment and extreme pressure.” While he didn’t refute these statements, he clarified that he personally hadn’t experienced such issues. He felt fortunate to have a strong “support system” that made the work pressure manageable and noted that he hadn’t witnessed or heard of any abuse by advisors toward himself or others. He also implied that some people may push beyond their limits without being “forced” to do so.

Nevertheless, he admitted that competition can be intense, not only among students but also between advisors, who seek academic success and power within their department. This pressure can trickle down to graduate students, who may not be fully prepared for it. He also noted that the rigid hierarchical structure in the Korean system can solidify the student–advisor relationship into a strictly professional one. I contrasted this with the situation in Europe, where departments often foster a community-like atmosphere, making it more common to develop friendships with advisors and fellow graduate students. This environment can provide “natural” support in case of personal problems or mental breakdowns.

Last but not least, when discussing the challenges faced by foreign students compared to Koreans, Dong-gyu suggested that they might lack a strong support network, such as family or close friends, to help share their burdens. He also noted that limited fluency in Korean can make it difficult to navigate society and find part-time jobs, especially during financial hardships. Interestingly, the PhD student saw the language barrier as a relative advantage. He explained that not being fully fluent in Korean allows him to avoid many “bureaucratic” responsibilities, giving him more time to focus on his research compared to local students.

As Korean universities continue to attract an increasing number of international students, particularly from Southeast Asia, they must pay greater attention to the vulnerabilities these students face, especially the risk of loneliness in a society that has yet to fully embrace multiculturalism.

The Author

Julien Laheurte is a French literary translator who has been residing in South Korea for the past two years. After the completion of his master’s degree in Seoul, he moved to Gwangju with the intention of delving deeper into the history of the May 1980 democracy movement. His goal is to translate literary works that shed light on this pivotal moment in Korean history.