Towards a Cashless Society

Written by William Urbanski.

There is a purveyor of coffee that operates stores all across the globe whose products I thoroughly enjoy. Their coffee is delicious and their stores are warm and inviting. Even their prices, which are more than I like to pay for coffee, are fair when considering the quality and overall ambiance. Furthermore, I have no opinion about their labor standards or anything like that. Despite all this, this franchise, whose name starts with an “S” and ends with an “arbucks,” recently instituted a policy that I cannot and will not support: their decision to stop accepting cash. We may be led to believe that using digital payments is just more convenient or even the way of the future, but who really benefits when stores abandon cash? I will give you a hint: not you.

The first reason for a store not wanting to use cash is that there are certain expenses that come with handling paper money. Counting and tracking money adds expense in terms of man-hours. Coins and bills delivered from a bank incur service fees. Although I am not sure of how much of a problem it is in Korea, there is also the risk of accepting counterfeit money. On top of these reasons, at least once in the history of mankind, an employee has “skimmed the till,” meaning “took out a long-term interest-free loan from his employer.” If a business is able to do away with these pesky expenses associated with cash, it does nothing but help the bottom line.

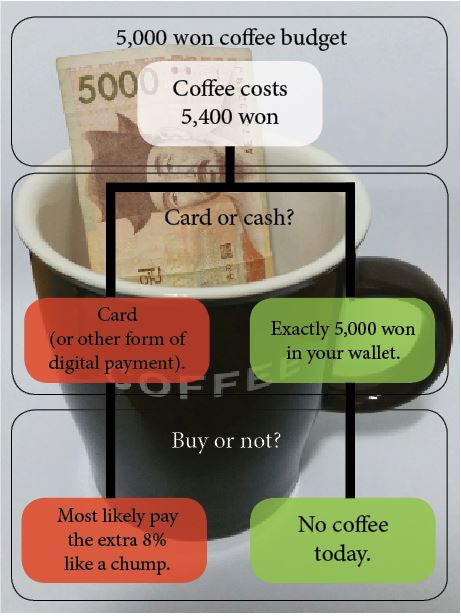

The second reason a business would want to do away with cash is more sinister: Businesses know that people who use digital payments spend more. Why this happens can be illustrated by a simple example. If Johnny has 5,000 won and wants to buy a coffee that costs 5,400 won, he will not buy the coffee. If Johnny had only “planned” on spending “about” 5,000 won on coffee and used his card to pay, he will most likely just say “whatever” and buy it. Well, in the second case, Johnny just paid an extra 8 percent. The fact that people pay more when using their cards is well-studied and well-documented.

“Nobody uses cash anymore,” I can hear you say. But let us be clear: Any establishment that demands digital payment is not doing it as a favor to you. They are doing it because in the heat of the moment, when the nice cashier tells you that that your coffee will cost 8 or 20 percent more than you planned, you will not want to look like a cheapskate to the people behind you in line and will pony up. Demanding digital payments exploits the taboo against appearing parsimonious to either the customer behind you or, gasp, to the cashier.

This whole trend of moving towards a cashless society is laden with problems. Among the myriad international examples, three stick out.

San Francisco recently pushed back against stores that accepted only digital payments, mandating that all brick-and-mortar stores must accept cash. The reason? The city considered not accepting cash a form of discrimination against the most vulnerable people in society: the elderly, the handicapped, recent immigrants (who often prefer cash precisely because the countries they come from suffer from poor financial institutions, so they do not trust anything but cash), and other numerically significant groups of people that, for whatever reason, do not or cannot have access to bank accounts or credit cards.

Recently in the UK, courts ruled that the biggest class action lawsuit in the history of Britain may proceed against Mastercard. The basis of the lawsuit is that all people in Britain paid higher prices due to excessive Mastercard fees. Not only does this tie into what I mentioned above with how people who use digital payments will simply pay more, but it also shows how overreliance on digital payments raises prices across the board. When a retail operation incurs an extra expense, such as the high transaction fees demanded by Mastercard, it will have to make up for that loss by passing on the high prices to the customer. Whether or not the class action lawsuit in the UK will result in every single UK citizen receiving a lump-sum payout or not, it sets the legal precedent that digital transaction fees raise prices and cause people to spend more.

Sweden, perhaps the most “cashless” society in the world, has experienced problems with its transition, even though most of society is on board with the change. Particularly hard hit are the elderly who in many cases struggle with using technology required to use and track digital transactions. Besides problems with adapting to the necessary technological change, there are somewhat comical examples of the issues created when the kroner is no longer king. Even public toilets, the last bastion of refuge for confused tourists and people who prefer to not do their business behind dumpsters in dank alleys, simply will not take coins. As well, in many instances, because they don’t keep any on hand, banks just do not allow people to withdraw or deposit cash. Weird.

The Digital Downside

This is a somewhat subtle thing, but while using digital payments may be a convenient thing, it is not necessarily a good thing or even a sign of progress in society. Furthermore, there is no nobility in using your phone to pay for a smoothie, and using digital payments makes you neither cool nor hip, and certainly not a member of the Digital Elite™.

Another often overlooked aspect of a cashless society is the way in which purchases are tracked and information is collected. In a world of targeted advertising, is it really a good idea to help people who would separate you from your money? Paper money offers a huge advantage over digital payments: anonymity in a way that no block-chain, crypto currency, or secure debit transaction, will ever be able to provide.

Embrace the Pain of Paying

The next time you fork out some cash for a coffee, a pair of shoes, or whatever, pay attention to that little bad feeling that accompanies someone taking your money. That is called the pain of paying. Even though you get something in return, there is a little and subtle feeling of loss because you had to give something up. Compare this to paying with a card: You hand over your card and the cashier hands you back your card, plus the item you wanted. On the surface, on a purely superficial level, you got something without giving anything up. Great, but this transaction obfuscates, or at least minimizes the fact that you just parted with your hard-earned money. This pain of paying is not a bad thing: It forces us to carefully consider our purchases. Embrace the pain of paying.

I am not here to rally against digital payments. There are many cases where digital payment is a good thing, but buying coffee is not one of them. Some (business owners especially) might suggest that a business has a right to determine how it will accept payment. To this, I have one word: poppycock. If a business wants to operate in a society, it should be forced to accept all forms of legal tender. In the same way that a restaurant in Korea cannot demand to be paid in Euros, a business, especially a retail operation, should in no way, shape, or form be able to reject paper won. In the end, providing coffee to the masses is not an essential service, and any coffee shop, especially a multinational one that operates under the umbrella of the Korean marketplace, should not be allowed to start dictating economic policy.

The Author

William Urbanski, managing editor of the Gwangju News, has an MA in international relations and cultural diplomacy. He is married to a wonderful Korean woman, always pays cash, and keeps all his receipts.