Gwangju Storytelling in the Jeonju Film Festival

By Patricia Aufderheide

At the 2024 Jeonju International Film Festival, where I had the privilege of reporting as a journalist (my article is at https://filmmakermagazine.com/125959-jeonju-international-film-festival-2024/), the challenge of recovering memory – or even of acknowledging when memory has been lost or suppressed – was everywhere. There were documentaries about Jeju 4.3, about hidden histories of women who suffered domestic abuse, about colonial-era Korean tweens who were seized to work in prison-like Japanese textile factories, about Zainichi women living out their last years in Japan but still dreaming of Korea.

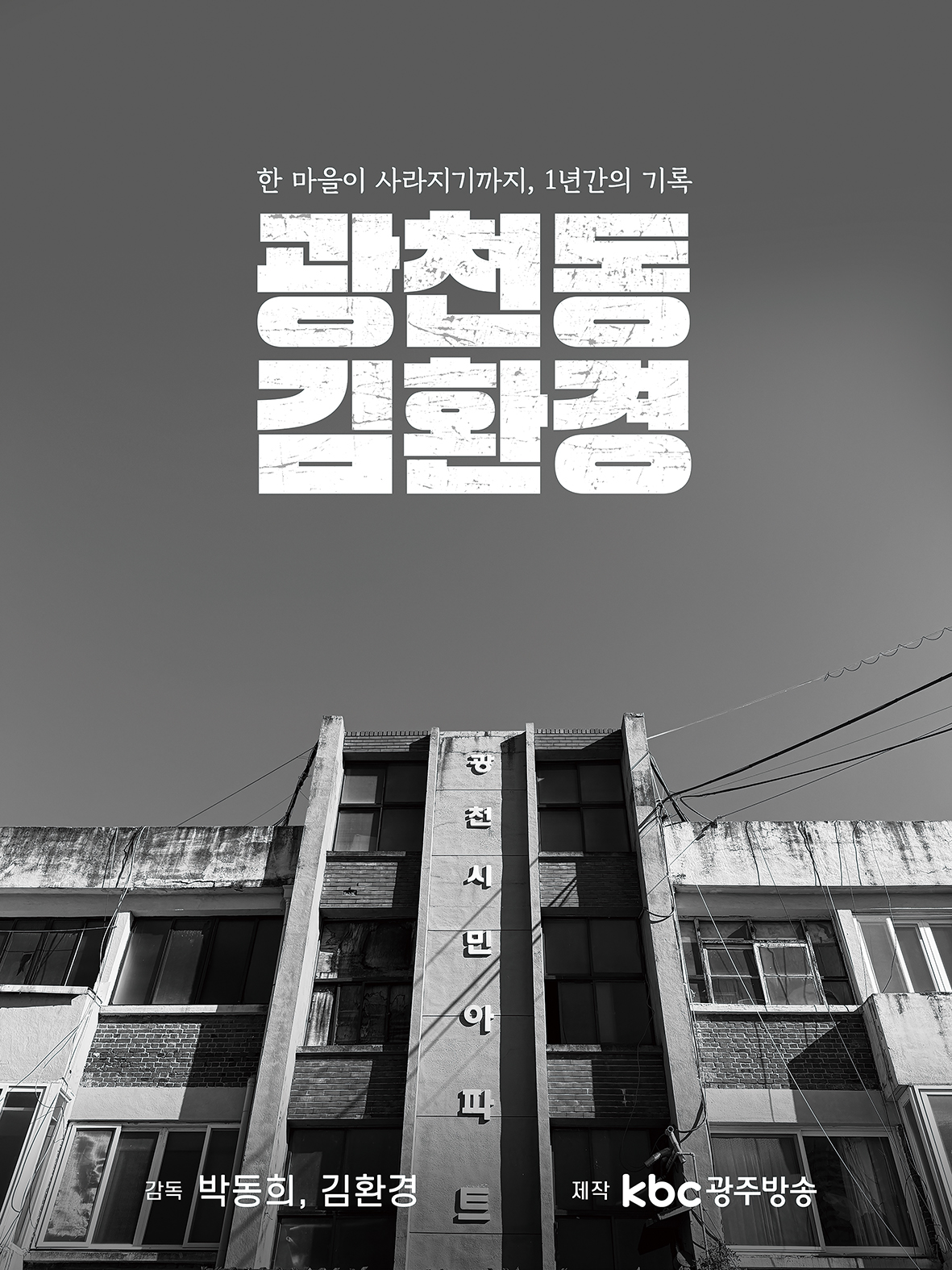

And there was a memorable documentary, Gwangcheon-dong – Mr. Kim, about a hidden history of post-5.18 Gwangju – hidden, at least, to Gwangju outsiders like myself. Kim Hwan-gyeong, a media artist and co-director with his friend, the local KBC documentarian Park Dong-hee, decides to take up residence in an apartment complex in Gwangju that is about to be demolished. This complex has a distinguished history. Poor, internal refugees who dreamed of grassroots democracy made it a communal project, and the Deulbul Night School(들불야학) flourished there. One of the complex’s leaders, democratic activist Kim Yeong-cheol, also protested in 5.18 and was savagely tortured, suffering physical and psychological damage from which he never recovered. The community, however, persisted into the present, with both its communal customs, such as shared meals, and its ideals. (The complex is included in the redevelopment area, and disxussions are being made for historical preservation, but this is also unclear now.))

The film gently makes the case that younger generations need to know and celebrate this history, through the self-deprecating persona that Kim Hwan-gyeong creates. He shows up, neither announced nor introduced, to a complex where the residents – who are fighting with the city water services – have no running water to the apartments. The residents are either suspicious of him or perhaps think he might be mad. The oldest woman there steadfastly ignores him, but finally the widow of the leader victimized in 5.18 builds a relationship with him. Gradually, as relationships bloom, the story not only of the complex’s past but of the still-vital values and democratic dreams of the residents emerges. And the growing relationship between Kim Hwan-gyeong and the residents shows how important building inter-generational bridges is. The film is to be shown on KBC after its festival run.

“Over the past decade that I’ve lived in Gwangju, I’ve seen that the story is so full of warmth, with so many interesting stories of individuals, which tell the human side of the pro-democracy movement,” co-director Park told me at the Jeonju festival. “The story of 5.18 is well known, but we wanted to tell one suffused with compassion. What lies inside of human hearts was at the root of democratization.”

It’s a film that has enriched my understanding of Korean documentary film, which I was studying in Korea as a 2024 Fulbright senior research fellow, at the Hankuk University of International Studies. The film also had a lot more meaning to me because I had made a trip to Gwangju on my way to Jeonju. There, with the help of Shin Gyonggu, head of the Gwangju International Center, and writer Lee Hye-yong, I had seen the site of the origin of the uprising at the university, as well as the memorials, cemetery, and museum. I had heard the stories of martyrs and survivors, and learned about the long process of recovering memory. This brought home to me the central importance of memory-building as a process of building Korean identity, as a democratic act, and an act of faith in democracy itself.

I had also visited the Jeju 4.3 Peace Memorial. There, the very first exhibit in the entire memorial drives home the importance of memory-making as a cultural and a national project. It is a plain, unadorned block of stone titled “Unnamed Monument.” Its caption reads, “As the Jeju incident still does not have historical definition, this monument has no inscription.” That is a powerful statement about the importance of the work of memory-making, and the scale of the work to be done. It is heartening to know that Korean documentary filmmakers have taken on this important work as their own, in the spirit of many who demanded democracy in Gwangju. The “historical definition” called for in the Jeju peace memorial is one that is developed through storytelling. Journalism, novels, films, and the personal contact across generations and cultures, such as I experienced on my trip to Gwangju, all do that crucial storytelling work.

The Author Patricia Aufderheide is a university professor in the School of Communication at American University, the author of among others Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press), and in 2024 was a Fulbright senior research fellow at the Hankuk University of International Studies.