Meet Martina Mittenhuber: Guest Speaker to Gwangju’s World Human Rights Cities Forum

Written by Farida Mohammed.

It was only 70 years ago, in the aftermath of the human devastation of World War II, as international leaders for the first time made an agreement to never again revisit such carnage, that the United Nations Human Rights Charter was conceived. In spite of the conflicts that wage today, modern history has countless examples of individuals in communities and cities promoting the furtherance of human rights. Gwangju, a city celebrated in Korea and abroad for its efforts to defend democracy and human rights, has shown the importance of cities and communities in shaping this history. The students who lost their lives fighting against colonial tyranny in 1929, the citizens that fought the military junta in the May 18th Uprising in 1980, and countless other events are examples of the city’s unified efforts to honor democracy and human rights. This enduring spirit of unity underscores the city’s efforts to further develop its commitment to human rights through events such as the World Human Rights Cities Forum (WHRCF) that Gwangju has hosted annually since 2012.

The annual conference, which brings together members of the international and local community, from public officials and policymakers to scholars in various academic backgrounds, dedicated to the promotion, study, and exchange of information in the area of human rights at the local and city level, will be held from September 30 to October 3 at the Kim Daejung Convention Center. Centered on the theme of “Local Government and Human Rights: Reimagining Human Rights Cities,” the forum will explore an array of human rights topics.

WHRCF guest speaker Martina Mittenhuber will address issues of gender and women’s rights in her presentation “Women-Friendly Village: Imagine Human Rights Cities for All.” Mittenhuber is head of the Office of Human Rights in the city of Nuremberg in her native country of Germany. Nuremberg, the center of the Nazi war crime hearings in the wake of the Second World War, is an interesting case study in how historical memory is studied and preserved as a resource to empower the furtherance of peace. Presently, the world is experiencing a resurgence of far-right extremism, a matter Mittenhuber acknowledges as posing a serious threat to the advancement of human rights. Her work analyzing and working in the areas of human rights and history for much of her professional career gives her insight into why and how cities should invest in promoting human rights at the local level. As a judge for the Nuremburg Award for Company Culture Without Discrimination and member of the Alliance Against the Right-Wing Extremism in the Metropolitan Region of Nuremberg, she is part of initiatives that encourage inclusion and a deeper understanding of communities that are becoming increasingly diverse. Through email, we conducted an interview and were able to get a snapshot take on her participation in this year’s forum, her thoughts on some of the pressing matters of international human rights, as well as her opinion of the WHRCF and women’s rights.

(©HRO)

Gwangju News (GN): Here we are, almost at the annual summit of the World Human Rights Cities Forum. What are some of the things you are looking forward to most about this event?

Martina Mittenhuber (Mittenhuber): Recent political, economic, and social crises seem to increasingly challenge the normative value and practical relevance of human rights. These crises – the rise of (neo-)nationalist populist politics, increased authoritarian rule, and challenges to international law and multilateralism have caused some to fundamentally question the current value of human rights. Others are even considering that the age of human rights is ending. Thus, communes are gaining importance as human rights “actors.” Many human rights and fundamental freedoms are implemented on a communal level first, especially in the area of social and civil rights. More and more municipalities all over the world are taking this task very seriously. They are always looking for ways to turn human rights into a guideline for living together in local communities. This is why I am looking forward to this exchange with colleagues and fellow campaigners from all over the world, and especially from Asian countries.

GN: As you are to be a thematic session speaker at the forum, I would like to know about the theme of your talk and what makes this an important topic today?

Mittenhuber: My talk this session, “Women-Friendly Village: Imagine Human Rights Cities for All,” will cover the topic of women’s politics in Germany and Nuremberg. Never before have women been as visible and, most importantly, as successful as they are today. The two areas that prove this point especially are employment and politics. Women have caught up when it comes to numbers: There are more women with academic degrees and more women with gainful employment. The number of women in leading positions has increased as well. The German and European legal foundations serve as the substance for gender equality – which is what women’s movements have been fighting for.

Still, behind this new picture of social and economic change, old patterns can be found. On average, women are paid significantly less than men doing the same work. They take on a lot of unpaid occupations including household work, children’s upbringing, and homecare. The #metoo movement has shown everyone the extent to which sexism has spread today, ranging from misogyny in advertisement to gender-based violence. In addition to this, several social and political movements described as “antifeminist” are openly spreading an outdated depiction of women and are campaigning against several achievements in the name of equality. In my talk, I will present to attendees how we approach these challenges in Nuremberg.

conference “Diversity in Nuremberg, 2016.” (©HRO)

GN: I can see you have a background in intercultural mediation, which I am sure has been helpful in your line of work. How have these skills helped you in your work with human rights? Are there any tips that you would like to share on intercultural mediation that could be useful at the individual or community level?

Mittenhuber: Human rights manifest themselves mainly in everyday situations. There is fair and equal treatment in school and in the workplace, as well as in social proximities like neighborhoods. At the same time, communities are places where interests of different individuals collide and provide room for conflicts. Conflicts happen because of contradicting needs of different parties. Whenever unbearable situations happen because of this, people may feel that their dignity is attacked and feel like they are not treated equally. Discrimination may well be the reason for this, as vulnerable social groups, and groups in need of protection, are affected by it. Of course, it is impossible to entirely avoid conflicts within a society. However, settling them is extremely important. Victims of discrimination are often afraid to take legal action, so mediation serves as a low-level instrument for dealing with conflict. Mediation empowers individuals. It makes it possible for them to find an agreement that is in everyone’s interests and therefore helps solve conflicts and bring peace to communes or local communities. Fulfilling my role as a human rights officer, I often serve as a mediator between civil society’s concerns and the normative restrictions of an administration. My mediative expertise helps me with that a lot as well.

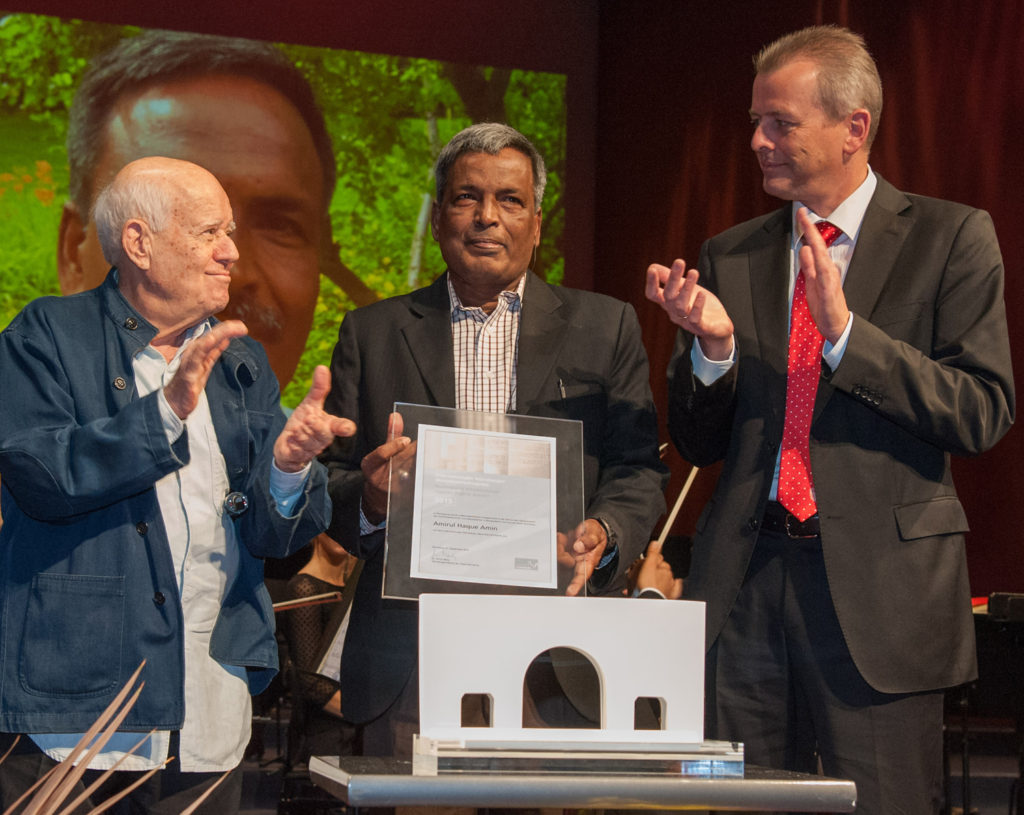

together with the laureate Amirul Haque Amin from Bangladesh and the Israeli

artist Dani Karavan, creator of the Way of Human Rights. (©HRO)

GN: In this age of technology and social media, we have seen an increasing mistrust of traditional sources of information and the coining of the phrase “fake news.” How does collective history and the work done by your office help fight against this challenging trend?

Mittenhuber: Media education is an important part of our human rights education programs. I believe that it is important to teach about media use nowadays, as media, and the internet especially, affect everyone’s life on a daily basis. Protecting everyone from fake news or online smear campaigns is impossible, so awareness-building and prevention are the keys. In addition to that, both our office and the City of Nuremberg as an institution are taking part in public discourse by having our own profiles on the respective platforms. The Human Rights Office is active on Twitter, where we share relevant information about our work and support other projects, and then there is our own website as well. Therefore, you could say that we are fighting fake news by sharing the messages that we believe in.

The Way of Human Rights, created in 1993 by the Israeli

artist Dani Karavan. (©HRO)

GN: With the rise in far-right extremism across the globe, extremely vulnerable groups such as refugees and asylum seekers are becoming targets of violence, an issue fundamentally linked to the diplomatic goals of the United Nations and Human Rights Charters. What do you think are some of the best ways cities and individuals can fight against this trend?

Mittenhuber: Right-wing populism uses unsolved global problems for its own benefit: climate change, financial crises, hunger, inequality, social divisions. Therefore, we need to establish a new conversation within society and constructive rivalry on both national and global levels. We need new ideas to solve the problems that already exist. Locally, we have to deal with far-right extremism and right-wing populism when it comes to mindsets. New strategies are needed in living together as a community. Something that is very important to me is labelling inhumane behaviors as such. There is no excuse for making allowances, as they are not harmless. We need to react to right-wing smear campaigns in Germany, especially those concerning both old and new antisemitism.

left). (©HRO)

In Nuremberg, human rights education serves as one of our central instruments when it comes to immunizing against group-based hostility and racist and antidemocratic mindsets. Being aware of fundamental human rights means being aware of the fundamental values of a diverse, open-minded, and dynamic society. Another important part is the solidarity between public administration and civil society when it comes to dealing with extremism and racism. Thus, local alliances are in need of recognition as well as political and financial support from public institutions. In Nuremberg, we have agreed upon getting into conversation with people who are prone to falling for hateful ideologies. At the same time, we need to fight against those who endanger our liberal democratic constitution.

GN: What do you look forward to about summits such as the WHRCF in their ability to impact development at the city level on human rights?

Mittenhuber: Summits like the WHRCF provide an exchange between different cities. Seeing how other places approach similar challenges allows us to take on new perspectives. Human rights are universal, but what we do to protect them differs from city to city. Meeting up with colleagues from around the world makes for a unique possibility for sharing our experience.

Photographs courtesy of Martina Mittenhuber and Human Rights Office, Nuremberg (HRO)

The Author

Farida Mohammed is an English teacher, avid reader, and novice writer living in the Jeonnam region. Before Korea, she lived in Spain, where she taught English, and prior to that, she worked in the field of human rights and migrants’ rights in the U.S. She has a degree in political science, Spanish, and international relations, and her main fields of interest are immigration rights and sustainable development.