South Korea’s Obligation to Refugees

Written by Praveen Kumar Yadav

One chilly January morning this year, a 25-year-old lady landed at Incheon International Airport. She had a narrow escape from prosecution by the Thai government.

She is young but brave. As a pro-democracy activist, she led many peaceful demonstrations against the junta. On some occasions, the military arrested her and later set her free after interrogations. But this latest occasion was the first time she had been given a charge of lèse-majesté for sharing a BBC article on Facebook. The article had mentioned serious allegations about King Vajiralongkorn (Rama X) and his involvements, ranging from philandering and gambling to his extravagant lifestyle and illegal business.

Thailand’s lèse-majesté laws protect the royal family by prohibiting public discussion about succession. The laws are strictly implemented by the current military government led by Prayuth Chan-ocha, the army general who led the overthrow of Thailand’s elected government in May 2014.

No sooner had she received the notice from the government than she rushed to Bangkok Airport. She could not bid adieu to her family and friends. Nevertheless, she has inspired them and others who believe in democracy and human rights, and they are currently resisting the junta in Thailand.

The democracy activist is Chanoknan Ruamsap, who is now in Gwangju, South Korea. According to her, she did not want to end her life in prison like many of those facing similar charges; many have suffered hapless fates and even passed away behind bars.

In March this year, she applied for refugee status in South Korea. But she is not sure how long the application process will take. The process generally takes five years or more. Furthermore, South Korea’s refugee acceptance recognition rate is low. Until she is conferred refugee status, she worries about her life in South Korea.

Like Chanoknan, there are tens of millions of forcibly displaced people worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, or human rights violations. Such people, also termed persons-of-concern, include refugees, internally displaced people, returnees, stateless persons, and others of concern.

By the end of 2017, the population of persons-of-concern was some 71.4 million around the world, as per the data maintained by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). UNHCR, established by the UN General Assembly in 1950, is mandated to lead and coordinate international action for the worldwide protection of refugees and the resolution of refugee problems.

Among the 65.6 million persons-of-concern in 2016, there were nearly 22.5 million refugees, over half of whom were under the age of 18, as per UNHCR. The number of refugees has increased by 5.4 percent in one year with the uptick in the number of the people of concern.

In the short span of just a few weeks in 2017, more than 600,000 people (Rohingya) from Myanmar fled to Bangladesh. This was the most rapid overflow since the massive refugee crises of the 1990s, as per UNHCR’s Global Report 2017. Likewise, other persons-of-concern were displaced last year fleeing war, violence, and persecution in the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, South Sudan, and Syria, among other countries.

Global trends show that state violence, human rights violations, conflicts, disasters, and risks to human lives due to various circumstances are on the rise and consequently forcing thousands of people every day to flee their homes in search of safety and protection. This requires more resources to ensure their safety and safeguard their rights.

Aside from the limited capacity to safeguard their rights, the search for safety has also become more dangerous, as per the Global Appeal 2018–2019 issued by UNHCR.

Recently, some of the receiving states, which were somewhat impacted by refugee arrivals, have closed their borders. The premature return of refugees equally affects their sustainable safety. Similarly, the journeys in search of safety are full of risks, including life-threatening violence and exploitation, detention, and torture. Weak international cooperation has also eroded protection for those forced to flee.

As the global community has recently marked the 18th World Refugee Day (June 20), the states and the stakeholders should come forward to address the aforementioned challenges consisting of limited capacity and risky searches for safety for the growing population of persons-of-concern. On this international day, the world needs to send a message – the world supports and stands with refugees.

Since 2001, the world has been observing World Refugee Day after the UN General Assembly unanimously passed a resolution on December 3, 2000, to mark June 20 as such. The first year of celebrating the international day for refugees coincided with the year when South Korea recognized its first refugee.

In 1992, South Korea became a party to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, and started accepting asylum seekers in 1994. However, the first asylum seeker was conferred the rights of citizenship only in 2010. He was an Ethiopian man who fled persecution in his homeland and arrived in South Korea in 2001. Still, South Korea stands among Asia’s few countries that have signed the 1951 Refugee Convention, and among the even fewer who have extended the rights of citizenship to refugees.

With the enactment of the Refugee Act in July 2013, South Korea has become the only Asian country that has a stand-alone refugee law clearly stipulating the rights and obligations of asylum seekers, those granted humanitarian status, and refugees, while also covering all major areas concerning the protection of those persons. In light of these facts, the country appears to be making impressive strides toward supporting and protecting existing refugees.

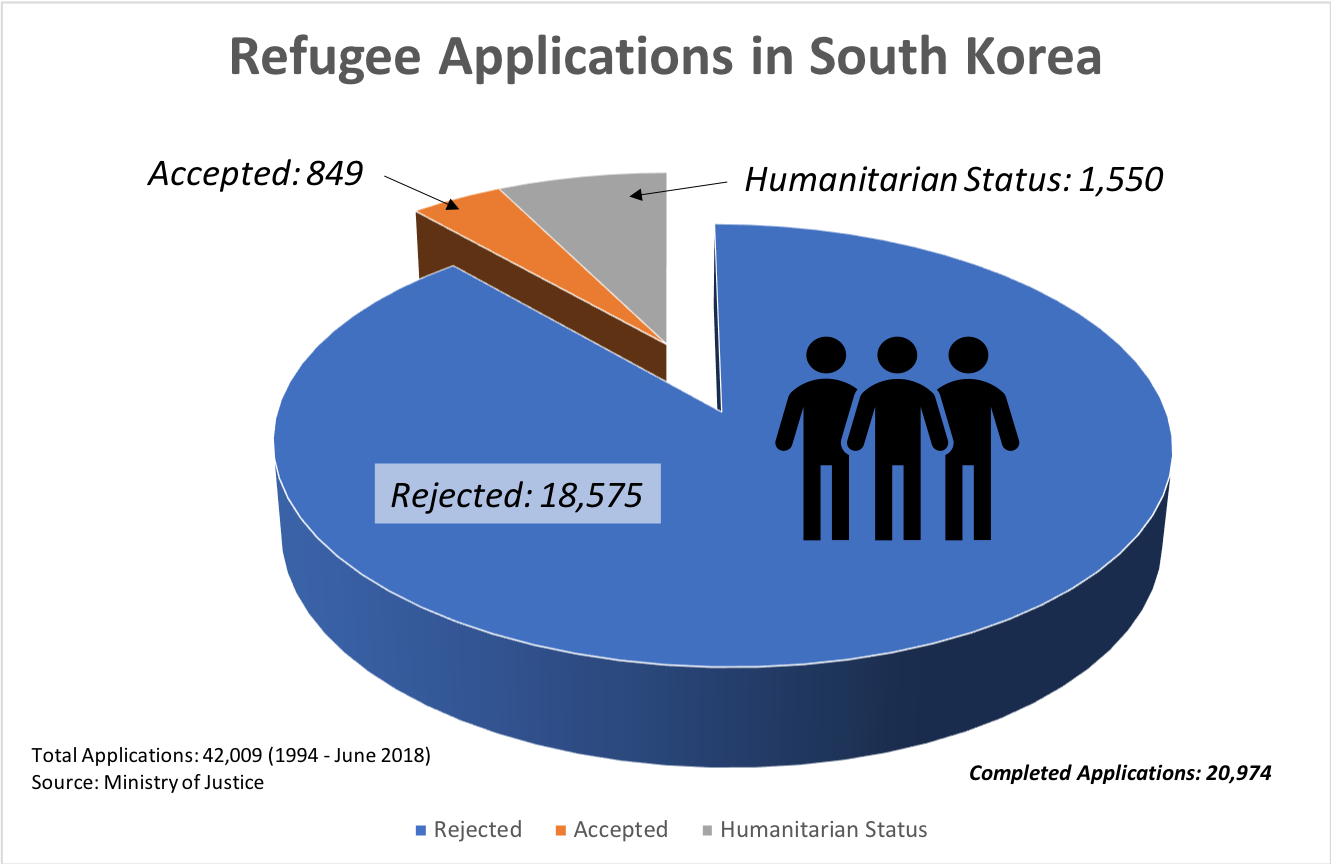

However, the refugee acceptance rate (3.9 percent from 1994 until April 30, 2014; 1.54 percent of total applicants in 2016; the status of refugee applications as illustrated in the graphic above) is low.

The Author

Praveen Kumar Yadav, who is a human rights researcher from Nepal, is an international intern at Gwangju-based May 18 Memorial Foundation. He tweets at @iprav33n

Disclaimer: As is always the case with our Opinion pieces, the views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Gwangju News, the GIC, or the Gwangju city government.

Praveen Kumar Yadav, It is great for you to share this story with the GN readers. I also hope that we can invite her to speak at the GIC soon in the future.