Jang Bo-go and the Rise and Fall of Unified Silla

This month’s Blast from the Past takes us deep into Korean history almost to the time “when tigers smoked pipes”

(호랑이 담배 피던 시절), back past the Joseon Dynasty, past the Goryeo Dynasty, past the Later Three Kingdoms era, and back to the Unified Silla period. Jang Bo-go was the naval officer protecting the coastline and waters of the Jeolla region. This article is from a two-part series penned by Won Hea-ran, “Jang Bo Go and the Sea Kingdom” and “Zen Buddhism in Unified Silla,” which appeared in the June 2015 and July 2015 issues, respectively, of the Gwangju News. — Ed.

Jang Bo-go, the Commoner Commander

In ancient times, it was very unlikely for a commoner to obtain the power and status of a general. Jang Bo-go went much further than that. As a general, he eliminated Chinese pirates attacking Korea’s coast and made his country prosperous through active trade. Ultimately, Jang rose to be an important political figure in the Unified Silla period.

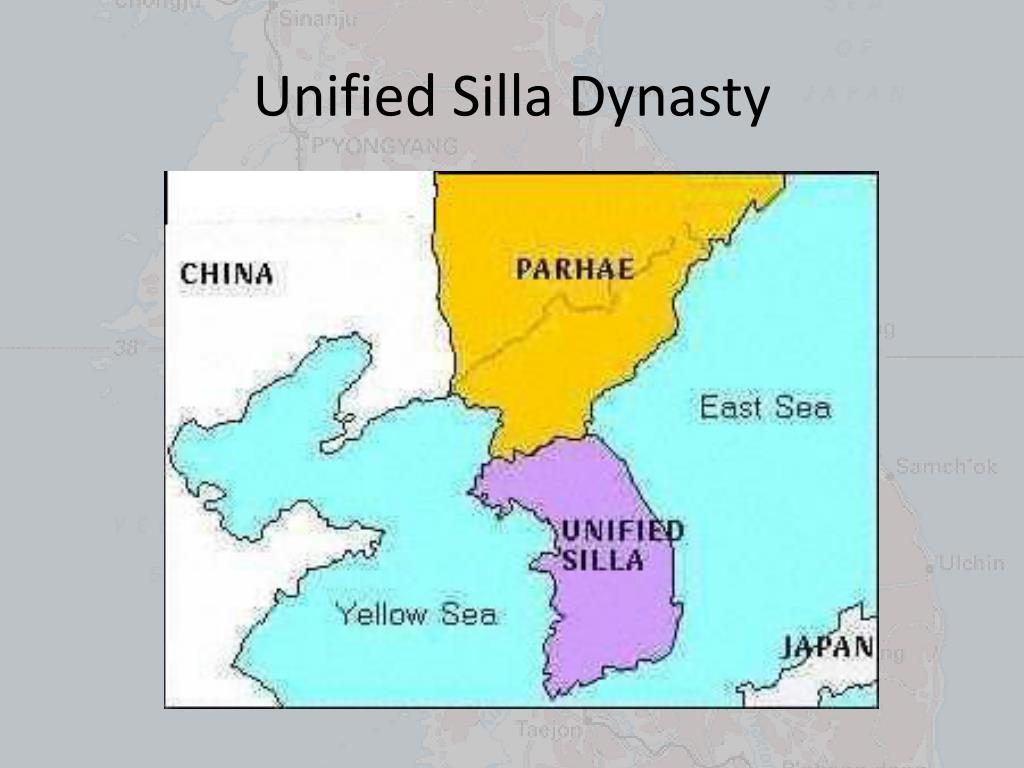

Jang was born in the late 700s AD. It was about a century after Silla had won its fight with rivaling states and finally unified the peninsula. Unified Silla, however, still had many problems. Chinese pirates were plundering coastline villages and trade ships. They captured the people of Silla and sold them as slaves in Tang China. Jang was born in a hard time to be alive.

Jang originally did not have a given name. (Historical records however do record his given name variably as Gung-bok or Gung-pa.) Although there is not much known about his family or birth, Jang must have been from a commoner family because only noblemen could possess given names. Historians assume that he gave himself the given name Bo-go when he moved to live in Tang China for a few years. Because everyone in China had a given name, it would have been easier for him to work in China with a given name. During his stay, Jang proved his talent as an able soldier and commander. He worked as a military officer in a coastal region of China called Seoju and reached the status of high commander when he was still in his 30s.

Jang Bo-go was a very righteous man. While working as an officer in China, he witnessed how many Silla slaves were captured and sold in Tang China. He returned to Silla in an outrage. In 836 A.D., Jang met with King Heung-deok of Silla and created a military base named Cheonghae-jin. The base was located at Wando, a southwestern island and Jang’s birthplace. From this naval base, Jang completely eliminated the pirates from the seas in just a couple of years and created safe trade routes for Silla merchants.

It was the beginning of a great “sea kingdom,” as General Jang had not only eliminated pirates, but also united Silla merchants to work together. He and the Silla merchants dominated trade among Tang China, Unified Silla, and Heian Japan. Thanks to Jang’s efforts, Unified Silla became prosperous and influential, enough to be recognized as a major power in the region.

Zen Buddhism in Unified Silla

The events surrounding Jang Bo-go’s death remain unclear, but it appears that he was assassinated by an emissary of the Silla court dispatched to meet Jang at his Cheonghae-jin base. The king and/or the Silla aristocracy were disgruntled with Jang’s attempts to have his daughter marry into Silla royalty. After Jang’s assassination (846 A.D.), Unified Silla gradually lost power. Political chaos and corruption led to local rebellions. The central government became so powerless that local nobles started to build their own military forces and rule their individual regions without any interference from the central government. Local rulers who gained freedom from interference in this manner gradually spread their influence over the spiritual realm of ideology as well. This led to the introduction of Zen Buddhism.

Before the central government started to lose power, Unified Silla was mostly ruled by non-Zen Buddhism such as Hwaeom Buddhism. Non-Zen Buddhism emphasized interpretations of Buddhist scriptures and doctrine, and its various factions were named after the main scriptures that they followed. For example, Hwaeom Buddhism followed the sutras of Hwaeom, and Yeolban Buddhism followed the sutras of Daeban Yeolban as their basic scriptures. The emphasis on scriptures is conspicuous in their temples’ architecture. For instance, Hwaeom temple has Hwaeom sutras written on the sides of three floors of its tower. Because non-Zen Buddhism considered the ability to interpret difficult characters more important than asceticism, it could only become the religion of the central government.

In contrast, Zen Buddhism put emphasis on spiritual fulfillment by performance. Zen Buddhists believed anyone could be a Buddha with absolutely no knowledge of the scriptures if they performed asceticism and perfectly understood the nature of Buddhism. While non-Zen Buddhists claimed that “The king is the Buddha and the country is the Pure Land of Buddhism,” Zen Buddhists said, “I (who found enlightenment) am the Buddha and where I stand is the Pure Land of Buddhism.” While previous non-Zen Buddhism gave the central government the right to rule, Zen Buddhism supported local families, providing self-confidence that they themselves could rise under the idea that “Buddha = power.”

Zen Buddhism was most influential in the Jeolla region. Out of the nine most famous Zen temples, the Jeolla region had four of them in the late Unified Silla period. This was because the monks who studied abroad in southern China usually returned to the southwestern coast of Korea. The support of local nobles such as Wang Geon also helped Zen Buddhism to spread in the Jeolla region.

Zen Buddhism was more than simple religion. The public saw hope; the local families saw ambition; but the central dynasty and nobles saw Zen as a threat to their original system. Ultimately, Zen contributed to the fall of the Silla kingdom and the birth of a new dynasty, Goryeo (918–1392 AD).

Arranged by David Shaffer.