The Donghak Peasant Rebellion: A Bloody Chapter in Jeolla History

When we think of history-making uprisings centering on the Gwangju area, we immediately think of the May 18

(1980) Democratization Movement. Some might also recall the Gwangju Student Independence Movement of 1929.

Few, however, will recollect the Donghak Peasant Rebellion of the late 19th century, though it was a struggle involving

many more casualties than these other two and arguably the initial crusade for democratic reforms in Korea. This

article is from a two-part series penned by Won Hea-ran, “The Donghak Peasant Rebellion, Parts I and II,” which

originally appeared in the January and February 2015 issues of the Gwangju News. We hope you enjoy them as

republished here. — Ed.

In the late 1800s, corruption was everywhere in Joseon Korea, but it was especially rampant in Jeolla Province [consisting of today’s North and South Jeolla provinces]. Perhaps Jeolla’s rich farmland made the region a desirable target for corrupt officials.

The governor of Gobu [present-day Jeong-eup, north of Gwangju], Jo Byeong-gap, was one of those unscrupulous officials. He exploited the region’s citizens through high taxes and intimidated them with false criminal accusations. Once, he took 1,000 nyang (billions of won in today’s currency by some estimates) from his people to build a commemorative monument to his father. He also unnecessarily levied a tax on water from a reservoir after using farmers as laborers to build it. Many people grew angry with the governor’s harsh mandates. Among them was the future leader of the Donghak (or Gobu) Peasant Rebellion, Jeon Bong-jun (전봉준).

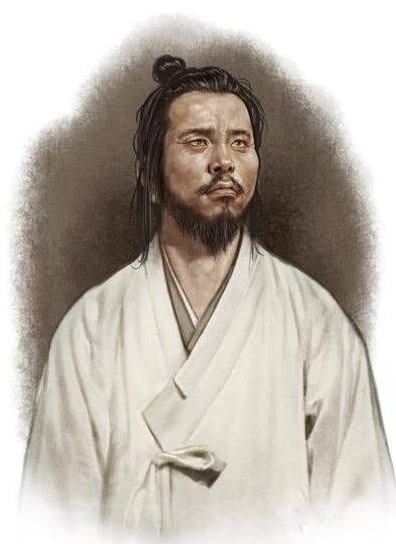

Jeon Bong-jun, leader of the Donghak Rebellion.

THE FIRST REVOLT

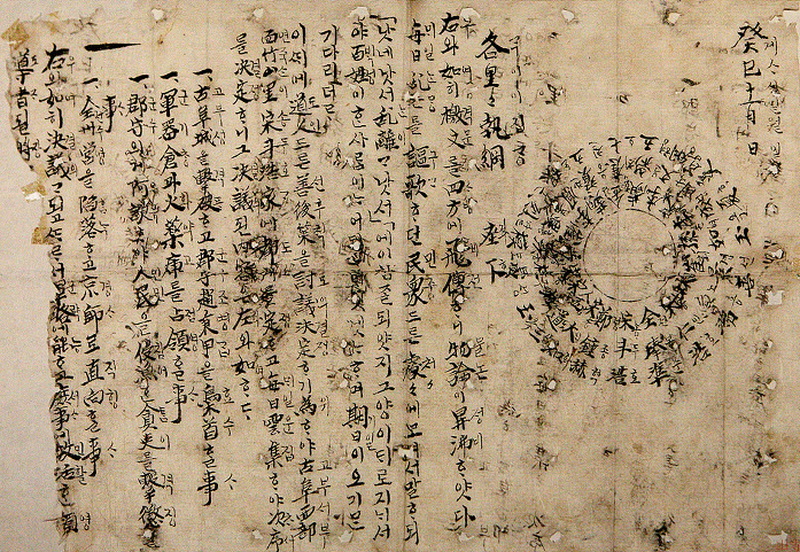

Jeon Bong-jun was the son of a fallen aristocratic family. As a young man, he was greatly influenced by the religious ideology of Donghak (동학, “Eastern Learning”). When Jeon Bong-jun’s father was killed for criticizing the governor, Jeon Bong-jun planned the Gobu Peasant Rebellion. At the end of 1893, he gathered farmers who were angry with the governor and wrote their names on a document known as the Sabal Manifesto (사발통문). The names of the 20 participants were written in random order to make it harder for officials to pinpoint the group’s leader. In January 1894, Jeon Bong-jun and his followers attacked a government office. At first, the rebellion did not get much attention. The incident was viewed by outsiders as a small village quarrel, but it turned out to be the start of a far greater uprising.

Jo Byeong-gap eventually fled and was replaced by a new governor. The newly appointed governor, although not as

greedy as his predecessor, punished farmers for stirring up unrest. He also criticized followers of Donghak, viewing the ideology as responsible for the rebellion. In March of 1894, the farmers collaborated with Donghak members to fight against the government. The movement spread across the Jeolla region, including villages like Buan, Gochang, and Heungdeok. In this First Donghak Revolt, the rebel army won every battle. Even the royal army could not stand against the rebels and their anger toward the government.

The farmers showed remarkable ingenuity as warriors. During a conflict at Hwangto-hyeon, the rebels cleverly remodeled a chicken house into a weapon that shielded them from bullets. Finally, on April 27, only a month after the struggle began, the fortress at Jeonju fell into the hands of the rebel army.

When the government finally realized how serious the situation was, it asked for help from the Qing Dynasty of China. This distress signal turned out to be a terrible mistake. It not only brought 2,000 Qing soldiers into Korea but also attracted 8,000 Japanese troops who had been searching for an excuse to intervene in Korean affairs. Threatened by the sudden military involvement of Japan, the Joseon government called for negotiations with the rebels to end the struggle as quickly as possible.

The First Donghak Revolt came to a successful end for the rebels. In negotiations with the government, the rebels succeeded in negotiating a treaty that defended citizens’ rights. These reforms abolished slave ownership, gave widows permission to enter into second marriages, and redistributed land. It is seen today by some as one of the first steps toward Korean democracy. However, it also paved the way for Japanese interference in Korea.

THE SECOND REVOLT

The First Donghak Revolt, ignited by a small village uprising, brought many great democratic changes. The reforms signed by the government and rebels burned documents on slave ownership, prevented any tyranny caused by corrupt officials, gave widows permission to remarry, and divided unfairly taken government land equally among farmers. The most noteworthy reform was the establishment of a Jipgang Hall (집강소) in 54 Jeolla Province villages. The Jipgang Hall was an independent commoner organization that supervised village officials and continuously worked for democratic reforms. With the rebels’ power dominating in Jeolla Province, the Jipgang Hall performed most of the village politics in place of government officials, particularly maintaining security and public order.

However, the First Donghak Revolt also opened the country up to foreign intervention. The government’s fear during the First Revolt led it to call upon China for help, which not only brought 2,000 Chinese soldiers but also four times that number in Japanese fighters, troops who had eagerly been looking for an opportunity to take part in Joseon politics. The Japanese military intervention greatly surprised the Joseon government, causing the government to hurriedly sign a reform plan with the rebels, and thus have the Japanese soldiers leave Joseon soil. But the Japanese forces remained and continuously influenced the Joseon government. The Japanese forces soon took control of Gyeongbok Palace, threatened King Gojong, and established a proJapanese group inside the government. Making the situation even worse, the Japanese forces defeated China in the Sino-Japanese War (1894), leaving Korea completely isolated and vulnerable to the Japanese.

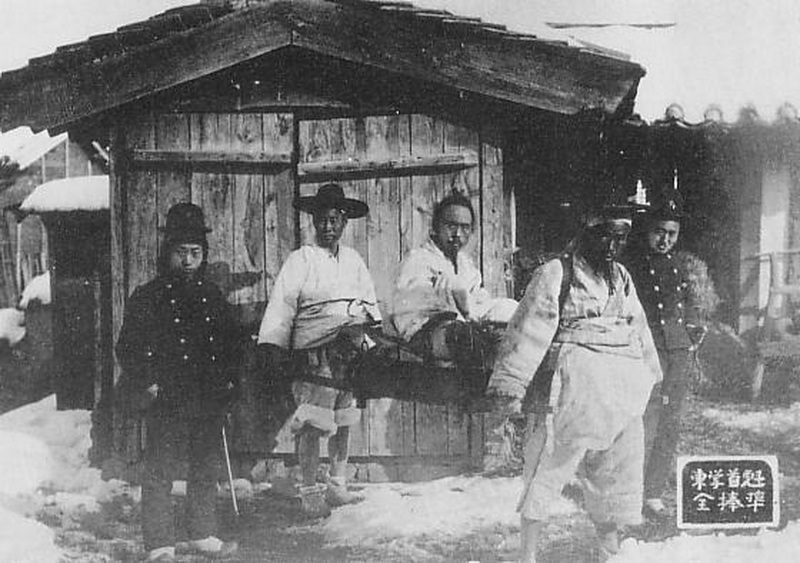

The leader of the Donghak Peasant Rebellion, Jeon Bongjun, realized that he could not overlook the situation, so he gathered his men from the former revolt and the entire Donghak forces to fight against the Japanese. In this second Donghak Revolt, the rebels fought against both Japanese troops and the Korean royal forces at Ugeumchi, Gongju, a region in Chungcheong Province between Jeolla Province and Seoul. The battle turned out to be a desperate struggle for the rebels. They were at a great disadvantage in both weaponry and position. The Japanese forces fired down on the rebels from their positions in the hills, mercilessly killing anyone climbing towards them. The Japanese also had advanced modern weaponry, including machine guns and cannons that were far superior to the agricultural implements that the rebels had to use as weapons. The massacre lasted for about a week, leaving only 500 alive out of the original 20,000-strong rebel force. Jeon Bong-jun was able to escape to Sunchang to prepare to take revenge, but he was arrested at Ugeumchi in December 1894 and executed. The rebellion was extinguished soon afterwards.

Although the rebellion failed militarily, it opened the door to modern reforms. The Donghak Peasant Rebellion was noteworthy in that it was not only one of the fiercest struggles by commoners for democratic reforms, but it was also the beginning of the anti-Japanese movement. Several of the later participants in anti-Japanese movements were originally involved in the Donghak Rebellion, including the leader Kim Gu, and its legacy extends to the March 1st Independence Movement of 1919.

FAST FACTS

- The number of fatalities in the Donghak Peasant Rebellion were approximately 6,000 Joseon government soldiers and an estimated tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of rebel fighters.

- The treaty ending the First Revolt contained these Donghak-side provisions:

• Accepting the Donghak religion

• Punishing corrupt officials

• Punishing other corrupt persons of the upper classes

• Punishing those who gained their riches illegally

• Freeing of all slaves

• Freeing all cheonmin (천민, “vulgar commoners,” the lowest class of commoners)

• Discontinuing the branding of butchers

• Legalizing remarriage by widows

• Lowering taxes

• Selecting politicians based on merit rather than on family ties - The famous Jeonju dish, bibimbap, originated as the food provided to the rebels fighting in the Jeonju area

Arranged by David Shaffer.