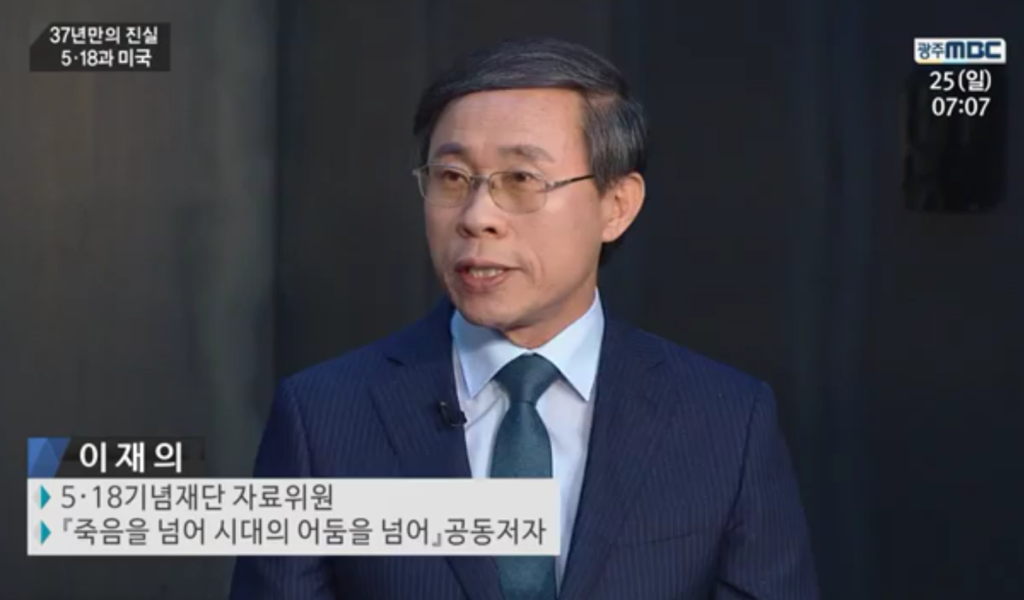

The Book That Sparked a Revolution: An Interview with Lee Jae-eui, Author of “Gwangju Diary”

Written by Wilson Melbostad

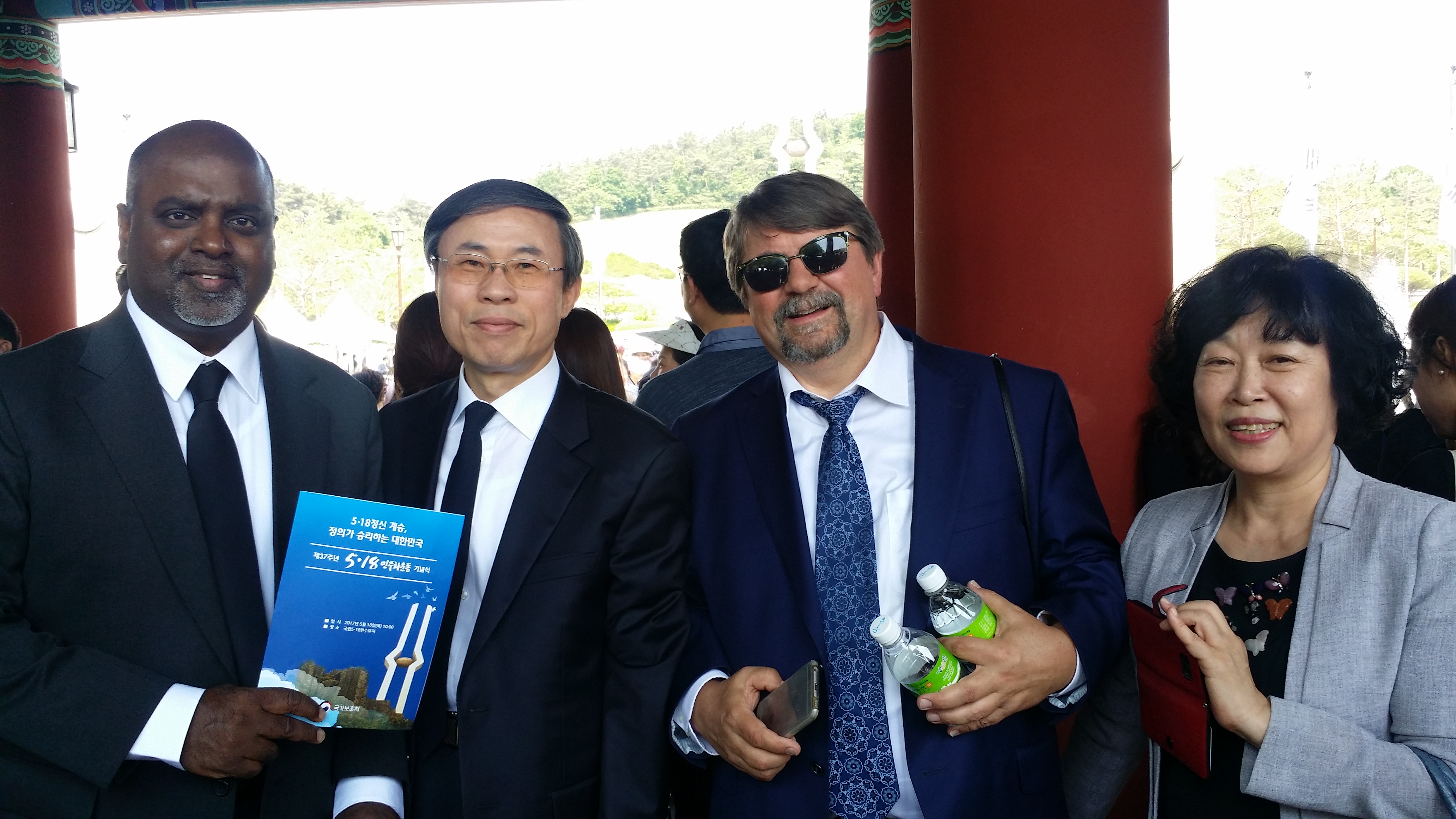

Photographs by Sarah Pittman and courtesy of the 5.18 Archives

As most residents of Korea will tell you, Gwangju isn’t just the name of a city in the southwestern corner of the country. Rather, the city of Gwangju and the Gwangju citizen-led May 18th Democratic Uprising represent South Korea’s long and arduous struggle for democracy. In short, the notoriously repressive ruler of the country, Chun Doo Hwan, declared martial law throughout the country on May 17, 1980, and accordingly dispatched troops to various parts of the nation, including Gwangju. The oppressive and violent tactics employed by the military in Gwangju to squash the protests there incited more citizens to join the democratic movement, thus beginning the ten-day struggle between Gwangju citizens and Chun’s military forces. Ultimately, the movement was suppressed but not before hundreds of civilians lost their lives in the process.

In addition to the suppression of the May movement, in the years that followed, Chun made concerted efforts to erase all evidence that the uprising ever took place. Those who spoke of “May 18th” were arrested and all newspapers and other books or publications relating to the uprising were strictly censored or prohibited from even being published. However, one book eventually did make its way into the hands of Korean citizens in 1985, Gwangju Diary: Beyond the Death, Beyond the Darkness of the Age. Author Lee Jae-eui, an eyewitness Chonnam National University (CNU) student at the time and freedom fighter during the uprising, worked for years while in and out of prison to fact-find and gather as much evidence of the uprising as he could since, as he put it, such efforts were critical to preserve not just Korean history, but human dignity overall. Though it was banned on an official basis, hundreds of thousands of illegal copies of Gwangju Diary were secretly distributed in Korea and abroad. The book was instrumental in bringing to light the atrocities that the state had committed against its own citizens and, as one might imagine, caused even more public distrust of the Chun Doo Hwan regime. Accordingly, the book is acknowledged as one of the sparks for the eventual “June Struggle” protests and ultimate realization of democracy in Korea in the summer of 1987.

The story of Lee Jae-eui’s trials and tribulations in publishing Gwangju Diary (including government-sponsored abuse surprisingly occurring nearly twenty years after democratization) is not as well-known as the extent of his sacrifice would suggest. Ten years of conservative Korean leadership during 2008–2017 saw many unsubstantiated allegations contesting the democratic nature of the 1980 uprising, insinuating North Korea was behind the “riots.” The South Korean Defense Ministry Truth Commission and the U.S. State Department, as well as countless other resources, have discredited such claims, yet the rampant use of political mudslinging seems to have temporarily muzzled Lee’s accomplishments.

Lee was an economics major at CNU at the time of the 1980 uprising, he had previously just returned from his three-year mandatory military service and was looking forward to rejoining his classmates for the spring semester. On May 16, 1980, Lee participated with his classmates in the “March of the Torches,” a peaceful demonstration on the CNU campus. According to Lee, spirits were high and those who were participating truly believed political and economic change was on its way. Yet, hope was quickly replaced by discouragement and confusion when on May 17, at exactly 11:40 p.m., Chun Doo Hwan officially declared martial law for the entire country (previously, the island province of Jeju had been excluded from the first order for martial law in October of the previous year). On the following morning of the 18th, riot police filled the streets of Gwangju. News of the brutal beatdowns and arrests of students spread quickly around the city, feelings of shock and bewilderment quickly turned into anger. Lee, one of the remaining students recalls the moment the student protests escalated into a citizen-wide movement:

“Suddenly, the next day [the 19th] people from all corners of the city began to join our demonstrations. We had never even imagined other citizens would participate since the repression of our student protests the day before had been so incredibly brutal. Yet nevertheless, the people responded and bonded together as one.”

The days that followed became more and more brutal as protests for freedom quickly turned into fighting for survival against the relentless military forces that had by then completely surrounded the city. May 20 (Day 3) of the uprising brought the infamous battle of Geumnam-ro (금남로, Gwangju’s main downtown avenue). Lee recalled the impact of the “taxi troops,” a squadron of Gwangju taxi drivers who committed themselves and their vehicles to transporting freedom fighters and the wounded:

“Once the citizens saw the taxis all committed to the cause, it marked one of the most important momentum swings in the uprising, from an unarmed demonstration to a show of defense for our city. The taxis’ bonding together was such a strong display of people power that it inspired others to join in the movement and defend their freedom. We cried because the scene was so incredibly overwhelming.”

However, by noon on May 21st, Geumnam-ro quickly spiraled into a war zone. “It just didn’t feel real. People were just collapsing right in front of me,” Lee recalled. “How could the army, supported by our taxes, be allowed to shoot at normal people?” The May 21 Battle of Geumnam-ro coupled with the previous evening’s May 20 Battle at Gwangju Train Station were some of the most violent of the entire uprising. Lee ventured to Jeollanam-do’s Provincial Hall on the morning of the 22nd (Day 5), one of the primary meeting places of the civilian army, only to be surprised with the news that overnight the paramilitary forces had completely retreated to the outskirts of the city. The scene at Provincial Hall, which served as an operation room for the citizens’ militia, was “chaotic” according to Lee. Many members were frantically debating about what to do before the military would inevitably return to try to retake the city. Lee aided in restoring order to the group and helped jerry-rig cars and buses to obtain fuel and other resources so as to sustain the resistance for as long as possible.

After two days of organizing weapons and resources at Provincial Hall, Lee returned home to rest, but as soon as he did, his family forced him to escape Gwangju as Lee would be a sure target if and when the military made its way back into the city. Lee accordingly snuck out via one of the foot paths the military had yet to block and stayed with his elementary school friends in the town of Gokseong, approximately 45 minutes outside of Gwangju. Sure enough, the military, backed with new enforcements from Seoul, reentered Gwangju and eventually completely defeated the civilian army on May 27 (Day 10). Lee, in Gokseong at the time, has always felt uneasy that he was able to escape while many of his friends sacrificed their lives for the cause:

“I have a feeling of survivor’s guilt. This feeling has always been in the bottom of my heart; I saw a lot of things during the uprising; many of my friends were killed by the paramilitary troopers. After the uprising was over, I decided to contribute my whole life to speaking on their behalf.”

Schools were later reopened, and in October, Lee, along with other surviving student freedom fighters, returned to classes at CNU. Following up on his promise, Lee began handing out pamphlets around campus inviting witnesses of the massacre that past spring to give testimony of what they saw. Eventually, Lee’s attempts were noticed by police, and on October 13, in the middle of a lecture, Lee was arrested and dragged out of the school. Lee, along with 30 other members of the pamphlet group were tortured inside the nearby police station for one and a half months. Lee was then transferred to a military prison, where again his body was beaten relentlessly for another three months. Lee was tried and sentenced in military court (martial law was still in effect) and placed in the notorious police torture facility, Samjeong Gyoyukdae in Seoul, as well as other minor prisons for a year before being eventually pardoned. Despite the risk of being sent right back to prison, Lee picked up right where he had left off and continued, alongside his colleagues, amassing as much data and testimony of the uprising as he could.

After tireless data collection, Lee began the months-long process of writing Gwangju Diary and ultimately was able to publish it in May of 1985. To hide Lee’s identity, Gwangju Diary was originally published under the penname of famous writer Hwang Sok-yong. The book became hugely popular as most in Korea had never heard of the Gwangju uprising before. (The government had kept it out of the news.) Though the book was banned, thousands of illegal copies were printed, leading to countless arrests of citizens caught with a copy. Many believe that the book served as motivation and as inspiration for the June Struggle of 1987 and ultimate elimination of Chun Doo Hwan and the regime. After the June Struggle, the Korean National Assembly heavily relied on the contents of Gwangju Diary for the 1988 open hearings to search for what truly transpired during the Gwangju Uprising. Gwangju Diary was also the most important basis for the prosecution of former leader Chun Doo Hwan in 1995 and again during the Supreme Court decision, which ultimately found Gwangju’s uprising to be democratic.

Lee has since translated Gwangju Diary into English (1999) but faced great pressure during the combined ten-year reign of conservative presidents Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye. It was during this tenure that Lee’s computer was hacked in an attempt to delete manuscripts of the Diary, and conservative groups continually attacked the legitimacy of his book, citing baseless arguments that the May 18 Uprising was in fact mobilized by North Korean special troops.

Towards the end of the Park Geun-hye presidency, likely in response to the news of the re-release of Gwangju Diary, individuals (Lee assumes either the police or the National Intelligence Service) began constantly following him and both wiretapping and hacking his phone. Lee was also forced to step down from his position as a secretary of Gwangju City Hall due to a politically motivated and frivolous lawsuit filed nearly three years ago accusing him of bribery, the trial for which is still ongoing. However, despite these attacks on Lee and the credibility of Gwangju Diary, he is confident that the results of the recent investigations into the May 18 Uprising will hopefully settle the score for the dwindling minority of those attempting to discount the heroism of Gwangju’s citizens. President Moon Jae-in’s arranged investigation, which concluded in February of this year, confirmed that the military had fired shots toward citizens from MD 500 and UH-1H choppers, with fighter jets armed with bombs on standby as a backup. Further similar affirmations are also expected after the National Assembly-commissioned May 18 Uprising Truth and Reconciliation Commission begins its investigations with full prosecutorial discretion later this September. When asked why these investigations and overall preservation of the uprising are so important to Lee, he emphasized the importance of sharing the lessons of truth moving forward:

“These kinds of experiences have to be shared for generations to come. We should always protect our freedom of democracy; we fought against a dictatorship, so I’d like to convey our experiences and the values we stood for to our sons and daughters. The people of Gwangju never gave up. What’s the real value in people’s lives? People fought for things more valuable than our own lives…freedom and human dignity. It’s imperative that we preserve these ideals for time to come.”

Reference

Lee, J. (2017). Gwangju Diary: Beyond the Death, Beyond the Darkness of the Age (rev. ed.). Seoul, Korea: May 18 Memorial Foundation. (Original English edition published 1999)

The Author

Wilson Melbostad is an international human rights attorney hailing from San Francisco, California. Wilson has returned to Gwangju to undertake his newest project: the Organization for Migrant Legal Aid (OMLA), which operates out of the Gwangju International Center. He has also taken on the position of managing editor of the Gwangju News.