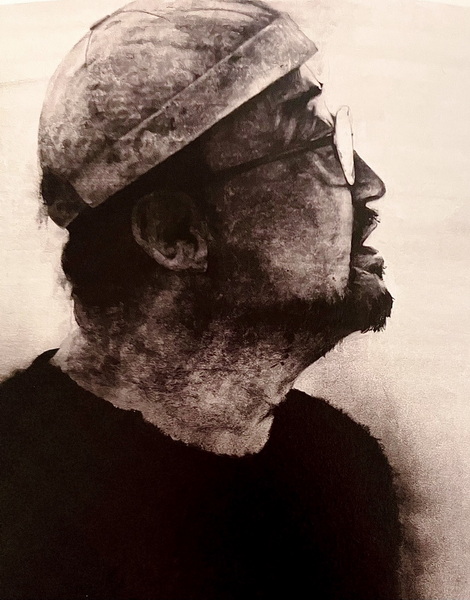

Chronicling the Pain of the Times: Artist Heo Dal-yong

By Kang “Jennis” Hyunsuk

Not long ago, there was an exhibition titled Yi Soon (이순, 耳順) by the artist Heo Dal-yong at the gallery Art Space House. “Yi Soon” refers to the age of 60, when one’s ears become gentler, and one considers things more objectively, and therefore more easily realizes the meaning of things – this is according to Confucius.

I had had a chance to see Heo Dal-yong’s artworks before. So, I wondered how his art might have changed since then. I remember his painting of President Roh, Man Who Became a Mountain. Roh Moo-hyun (1946–2009) was president of Korea from 2003 to 2008. He was a human rights lawyer and activist before he entered politics, and he was known for his progressive policies during his tenure. He committed suicide by jumping from a cliff near his home. His passing was a great loss to many common people in the country.

As one who remembered Heo Dal-yong’s earlier style in art, I wondered what changes might have taken place in his art at the age of the “gentle ears.” When I saw a long, white, and narrow road running between the deep, dark mountains in one of his paintings, I was surprised that the painting was so dazzling even though it was painted in only black ink. I thought the painting well suited the term “Yi Soon.” This memory prompted me to ask him for an interview for the Gwangju News. However, before having that interview with him, I did my research and found some detailed information about the artist and his family tree.

Heo Dal-yong was born into the Heo family, which was continuing the line of the painting referred to as namhwa (남화). Namhwa is a style of painting that originated in China. It is also called “literary painting” because this style was mainly painted by Confucian scholars rather than by professional artists. So, it tends to value the spirit of the paintings.

In the late Joseon Dynasty, the great scholar and calligrapher, Chusa Kim Jung-hee (1786–1856) accepted Heo Ryeon (1808–1893) as his disciple and recognized his painting as the best in Joseon. Heo Ryeon (1808–1893) was called the master of namhwa painting in the late Joseon Dynasty. His painting style was handed down to Heo Hyeong (1862–1938), Heo Gun (1908–1987), and their descendants. Another branch of the Heo family also has many artists in its ranks. Heo Baek-ryeon (1891–1977) of Gwangju fame and his younger brother, Heo Haeng-myeon (1906–1966), along with their descendants, are in this group of the Heo family bulging with artists. It seems rare in this world to have dozens of artists from a single family line in just 200 years. Armed with this and additional information, I set out for my rendezvous with artist Heo Dal-yong.

The Interview

Jennis: Thank you for granting this interview. I heard your grandfather and father were both traditional ink painting artists, and I imagine you naturally embraced becoming a painter in your childhood. When did you start painting?

Heo Dal-yong: Heo Haeng-myeon (1906–1966), the younger brother of Heo Baek-ryeon, passed away when I was a child, so I do not have a lot of memories of my grandfather. And from observing my father, Heo Dae-deuk, I never dreamed of becoming a painter myself because I felt that life as an artist was too difficult to make a living and have a family. Then, when I was in middle school, I felt that I was not very interested in studying at school. So, I told my father that I would study painting, and I started studying painting from the disciples of Heo Baek-ryun, my great uncle.

Jennis: What did you study in the beginning?

Heo Dal-yong: At first, I studied the Four Gracious Plants (plum blossoms, orchids, chrysanthemums, and bamboo) of oriental painting, and I enjoyed it very much.

Jennis: You entered the College of Art at Chonnam National University. What was your college life like?

Heo Dal-yong: There was an art club at the high school I attended, and the members of the art club were given a scholarship. So, I started my life in the art club and entered Chonnam National University as a Korean painting major in 1982, the same year that the College of Art was founded. As soon as I entered, the university was engulfed in a chaotic atmosphere. Park Gwan-hyun, the former president of Chonnam University, who was a leader in the protests in Gwangju in May, 1980, died in prison in 1982. The students of Chonnam University and the citizens of Gwangju were shocked. There was a protest every day to get to the bottom of what caused his death. And I had a college life of drinking makgeolli rather than studying.

Jennis: Since when did you start painting in earnest?

Heo Dal-yong:When I was in my senior year of college, my father had a stroke, and I had to do my army service. When I finished my military duty and returned to college, I met Professor Lee Tae-ho, who was teaching art history. Due to his influence, I joined the art group Gwangju Chonnam Artists Association and started an art movement. From then on, I have thought that I should paint my own paintings. So, I studied the works of the best painters of the Joseon Dynasty, such as Gyeomjae Jeong Seon (1676–1759) and Danwon Kim Hong-do (1745–1806), as my painting “teachers.” When I got stuck with my painting, I looked to them for inspiration. And I held my first solo exhibition in 1997 to highlight studying on my own.

Jennis: In your early landscape paintings, you depicted ordinary people’s daily life, such as a farmer working in the field, not that of people who leisurely enjoy nature. Is the child standing with a brush in one of your paintings your son?

Heo Dal-yong: Yes, that is right. My son also picked up a brush among the various things placed in front of him at his first birthday party. [In Korea, at the first birthday party, there is the tradition of predicting the baby’s future from what the baby selects from among various objects placed in front of him. For example, money signifies future wealth, a spool of thread represents longevity, and a pencil indicates becoming a scholar.]

Jennis: There is the White Night series among your artworks. I wonder why you named it “White Night”?

Heo Dal-yong:When I was working in civil organizations, I did not have time to pick up my brush during the daytime. I thought that an artist who did not hold his brush could not be an artist. So, I went to my studio on the outskirts of Gwangju late at night and painted. Sometimes I worked till dawn. That is why there are so many works of mine with White Night as their title.

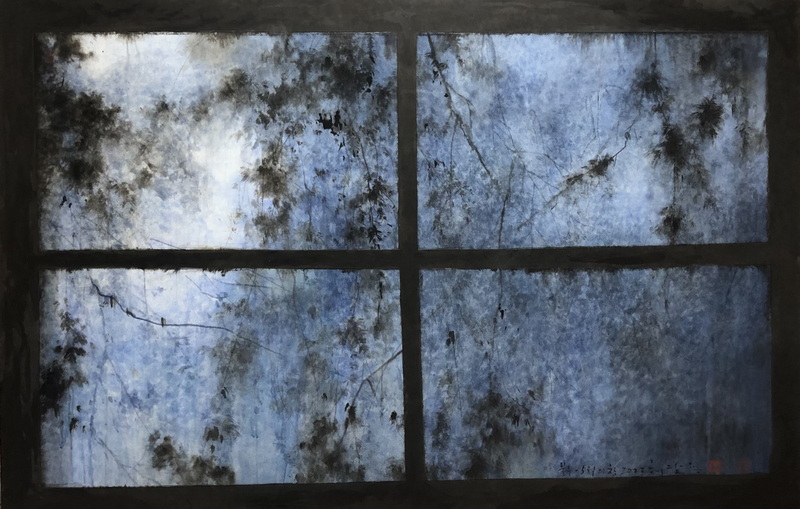

Jennis:What artworks have you created in relation to social movements?

Heo Dal-yong: When I was working in various civic organizations, I depicted social issues in a straightforward way. But now I want to express my own sensibility. A few years ago, when I stopped by the National Army Hospital, a May 18 historical site, I spotted the beautiful tree leaves outside the window of the building where wounded citizens had been dragged and locked up during the May 18 Uprising. I empathized with the injured citizens and how they felt when they looked out that window. I painted this feeling in Window of May. My expression has changed from the direct way, like painting blood and death, to delivering feelings in a more indirect way. It is a different way of telling stories about May 18.

Jennis: What kind of paintings have you done on other social issues?

Heo Dal-yong: I have painted social issues such as the candlelight vigil against the incompetent and corrupt government with the painting The Blue House with Lights Off. And I have expressed birds as the power of the people, as in the Hitchcock film The Birds. Birds are small individually, but when they gather, they can pose a fearful threat to a huge plane.

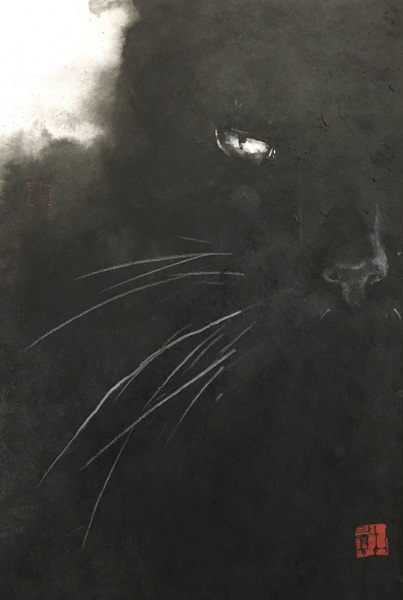

Jennis: A few years ago, you held an exhibition with only cat paintings. How did it come about that you began to paint cats?

Heo Dal-yong: Except for my son’s childhood painting, I think it was the first time I had painted close-up objects with such affectionate eyes. I was attracted to cats as a subject with their clear and big eyes, and various expressions in those eyes. The process of making friends with stray cats was also amazing. These days, I often paint cats.

Jennis: I think this could provide an opportunity to broaden the public audience who enjoy your paintings. What plans do you have for future painting?

Heo Dal-yong: I consider that ink-and-wash painting is the eternal assignment that I have to work on. However, as a member of this society, I also want to do something helpful.

Jennis: Your contributions to society have already been great! Thank you for this most interesting interview.

After the Interview . . .

Heo Dal-yong’s historical paintings have played the role of drawing attention to social issues from all corners of modern society. At the age of 60, he says that he wants to create paintings that he can talk with for a long time. I am a big fan of the ink-and-wash paintings of Heo Dal-yong, who carries on the family tradition of working in the arts, and I am looking forward to soon seeing his cat painting exhibition.

Heo Dal-yong’s Solo Exhibitions

- 2023 Becoming Sixty, 耳順; View from the Window (Art Space House, Gwangju)

- 2022 Heo Dal-yong Invitational Exhibition (Starry Night Street Art Gallery, Gwangju)

- 2021 Heo Dal-yong Invitational Exhibition (KimNetGwa Gallery 3, Gwangju)

- 2020 Loving Cats, 猫情 (Art Space House, Gwangju)

- 2019 Black & White (S.A.F. Cube Gallery, Gwangju)

- 2018 The 9th Memorial Requiem for Mr. Roh, Man Who Became a Mountain (S.A.F. Cube Gallery, Gwangju)

- 2018 Private Exhibition (G&J Gallery, Seoul)

- 2017 Black & White (GMA Geumnam Street Branch, Gwangju)

- 2016 Invitational Exhibition (Gallery Nori, Jeju)

The Author/Interviewer

Jennis Kang is a lifelong resident of Gwangju. She has been doing oil painting for almost a decade, and she has learned that there are a lot of fabulous artists in this City of Art. As a freelance interpreter and translator, her desire is to introduce these wonderful artists to the world. Instagram: @jenniskang