A Doctor for the Weak and Displaced: Interview with Dr. Cynthia Maung, Winner of the 2022 May 18 Gwangju Prize for Human Rights

By Arlo Matisz

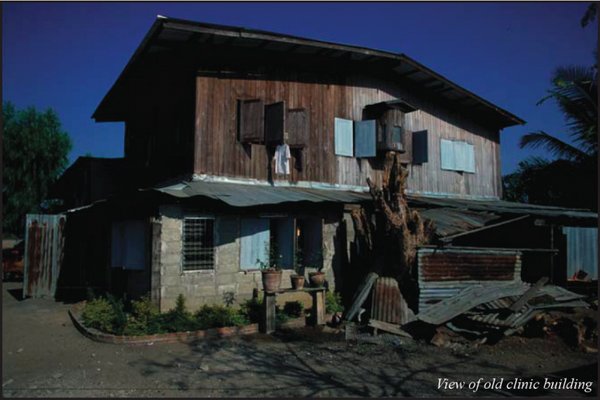

On May 19, 2022, Doctor Cynthia Maung was interviewed for GFN’s face2face program. Dr. Maung had just been awarded the May 18 Gwangju Prize for Human Rights award by the May 18 Memorial Foundation for her work providing health services to displaced persons and migrant workers at the Mae Tao Clinic, which she founded in 1988. The clinic is located in a refugee camp on the border of Myanmar and Thailand to provide medical assistance to Myanmar refugees who fled to the Thai border due to the oppression of the Myanmar military. Below is our interview with her.

Arlo Matisz (AM): Thank you, Dr. Maung, for joining us for the interview today. Could you please introduce yourself to our listeners?

Cynthia Maung (CM): I am Dr. Cynthia Maung. I have been working for displaced persons on the Thai-Burmese border since 1989.

AM: That is a very long time to do very good work. Thank you so much for joining us in the city of Gwangju! Now, obviously you have worked in this career for decades, and you were a doctor before that. What gave you a strong interest in medicine?

CM: I studied medicine in Myanmar and finished my studies in 1985. Since I was young, I have known that medicine is one of the most important things in my life, because my father was a healthcare provider. I joined my father and saw that many people throughout the world could not access proper healthcare services, so I wanted to work like my father and treat patients so people could enjoy their health rights through the protection and promotion of health.

AM: When did you start the Mae Tao Clinic, and what can you tell us about that time?

CM: I joined the 1988 pro-democracy uprising in Myanmar, but the military tracked down pro-democracy activists, so I had to flee to the border along with my colleagues and friends. Along the border area, we saw many internally displaced people who could not access healthcare services, and we also saw that malaria was prevalent. There were also many young people who suffered from mental health issues. So, I wanted to start helping those people and found a way to work with the local community. Then, with the support from the local community, we were able to set up the Mae Tao Clinic.

AM: So, your clinic is on the Thai side of the border, but you are helping people from both sides?

CM: Yes. So, initially, most of the services that we provided were for people crossing the border from Myanmar to Thailand. Today, because of Covid-19 and the lack of access to healthcare, people crossing the border need a place where they can get primary healthcare services, so we set up a clinic for local assistance that advances healthcare services.

AM: When you first approached the border after 1988, what did you see there and what made you realize that you had to work there?

CM: Initially, I worked in a hospital with women and children. The children suffered from malnutrition, and the women were delivering babies is a challenging environment, because there was no access to health facilities in such a rural area. So, in the beginning, when we started the clinic on the Thai side, we started to train local people as healthcare workers for the local community.

AM: How and when did the clinic get settled?

CM: Initially, it was supported by a local Thai community, because Thailand and Myanmar share a very long border, so there has been a relationship with local people. They speak the same language and work together on community development, community training activities, and education for children. With support from the local community, we were able to start our small clinic; medical supplies were donated by a local church group, and after a year, some international NGOs recognized that there was an office in place that, together with the local community, was able to provide treatment to these people, so they start giving medicine as well.

AM: Could you tell us what some of those organizations are that you worked with?

CM: In the beginning, the organizations were a local church group and the local community, and then gradually the Thai group “CONSORTIA,” which is one of the biggest consortium groups, supported us with help from different international NGOs from the UK, US, and Canada. So, we started working with them on food relief, and at the same time, the MSF (Medicins Sans Frontieres) was in the refugee camp to help out. Another organization called the Malaria Research Unit worked on the malaria control program, because most of the patients that we saw suffered from malaria, so we got training and medicine from these organizations.

AM: That is great that there was help that poured in, although I am sure you can always use more. How many people work at the clinic?

CM: The clinic has grown from a primary healthcare facility to a training center for healthcare workers, and we also started a job protection and education program in 1995, because we have seen that many women who deliver outside the healthcare facility cannot get access to nutrition. Children dropped out of school because their parents were very poor, so we expanded our services to include a job protection program. Currently, our staff for both the job protection and healthcare programs number about 250.

AM: And how many patients have visited the clinic on average?

CM: Starting from 1995, the Burmese economy started to deteriorate, and as a result, there were many migrant workers crossing the border from Myanmar, so gradually our patient number increased annually. The highest we had at one time was 200–300 patients per day for daily consultation. We also have an inpatient facility with 120 beds.

AM: Do you have any difficulties or issues while running the facility, because it is a free healthcare system?

CM: Yes, it has been challenging for us to run the facility. First, the location of the clinic is not idyllic. Also, the place is not really designed as a clinic, so sometimes it is difficult to provide good, quality healthcare services. We also receive vaccine support from the local Thai hospital. But we really need more understanding from the local Thai hospital, because most doctors and nurses there do not understand the situation of the migrants, the refugees, and the displaced people. Sometimes it is not just because of the language barrier; they do not understand the political situation in Burma, so cooperation and partnership are very important for our work. The people on both sides of the border are very poor and cannot always go for medical treatment on time, so they can miss the opportunity to get vaccinations. We also need to make sure that everyone gets full, complete treatment.

AM: From your perspective, what are some of the biggest challenges that people face?

CM: The challenge is the access to healthcare, the discrimination and stigmatization, because we are working with displaced migrant communities who speak different languages. For example, we do not speak the Thai language, and sometimes the hospital’s doctors and nurses who come from the city do not speak the local language, so the ethnic people, the migrant workers, and the refugees cannot access healthcare because of their identity, or because they cannot afford to pay for secondary healthcare services. In terms of resources allocation, we can see people cannot afford the facility, so these are the biggest challenges. The staff try to make sure that the poor people, or the marginalized people, can access proper healthcare service centers and emergency healthcare services. People who cannot speak the language are sometimes ignored and not given assistance.

AM: How have global health issues impacted your own life, or the lives of the people that you treat?

CM: I believe all people should have the right to access healthcare services, just as a child should get proper immunization and have access to a quality education, but we see many children are oppressed, so we need to foster a system to promote a better life for women and children.

AM: Now the world continues to experience extreme issues one after another, and the pandemic highlights the problem with global health, including food, security, and environmental protection, so do you have any particular passion where you would like to see changes?

CM: Firstly, we need better political relations to invest in the community, as sometimes we see political relations are not good. For example, in the Burma case, we have been under military rule for almost 17 years. There was a period of peace for some time, but now we continue to struggle along the border. Most of the people who suffer are women, children, and the elderly; they continue to be marginalized. To end the crisis, we need to invest more in political relations to better protect the rights and dignity of people, and especially provide access to healthcare and education for women, children, and the elderly. These are the key areas that we need to focus on, and at the same time, people displaced from their homes, like refugees, need to be managed, so addressing refugees and migrants not only in Myanmar but also in the whole region needs to be dealt with by many countries. We have seen the crisis up close, like the war, the displacement, and the refugees, so unless the government addresses this issue, conflict, violence, and prejudice will continue.

AM: Do you have any final words for us here in Gwangju?

CM: Firstly, it is an honor for me to be awarded the Gwangju Peace Prize, but this is also for all our staff, our community members, and our partners. We are not alone. Many people around the world fight for freedom, democracy, and human rights, and everyone wants a peaceful environment to work in. You want to see that children grow up in a safe environment like in Korea now, where children enjoy a good life, access to education, and health services. This is important to everyone, so we continue to work on that, and we try to make more partnerships with South Korean organizations like the May 18 Memorial Foundation. This reward encourages our staff to continue the struggle.

AM: From a human rights city to someone who has worked for human rights all her life, thank you so much for coming today, and I hope we can give that help.

Photographs courtesy of Dr. Cynthia Maung and the May 18 Memorial Foundation.

The Interviewer

Arlo Matisz is an economics professor and the host of GFN’s face2face. He is big-headed and big-hearted.