Media Art: A Universal Language Spoken by Artist Park Sang-hwa

By Kang Jennis Hyun-suk

Gwangju, the City of Light, has yet another name: Creative City of Media Arts. The city has been given this designation by UNESCO because there are so many media artists in the city pioneering this new field of art. In 2014, UNESCO selected Gwangju as a “creative city” for media art. The UNESCO Media Arts Creative City Gwangju Platform operates hologram theaters and media art archives, and also operates new media experience projects such as augmented reality (AR) for young audiences.

Nevertheless, numerous people around me have never heard of media art, or they do not know exactly what media art is. The birth of this new art form called “media art” seems to be confusing not only to traditional artists but also to people interested in arts. You have probably seen screens with paintings moving in them in government offices or in museums. And whoever passes through the main expressway tollgate to enter Gwangju cannot miss seeing the media artwork of Lee Lee Nam, the “Light of Mudeung,” towering over the tollgate. We are living in the world of media art without even realizing it.

Curiosity had me going to a dictionary to understand media art better. It said that media is a means of exchanging opinions, feelings, or information in society. However, people today have been moving away from mass media that provides one-way information, and are creating a renaissance era of personal media without borders and time constraints through blogs, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, and other digital media. In today’s world of social media, anyone can be a producer of contents and at the same time be a consumer. Now the young people want to be influencers through social media more than any other profession.

Combining Media and Art

What will art look like in the generation of digital natives? These art connoisseurs might just step into artworks and enjoy art by being part of it. Metaverse is a combination of meta, meaning “virtual, transcendent,” and a syllable of universe. In a virtual space called “metaverse,” we play games, buy and sell things, feel the speed of people walking, and see paintings in art museums. Like in the movie The Matrix, the virtual world is rapidly flowing into our daily lives. It seems to be a very distant future story, but some artists have already been doing such experimental artwork for decades.

The Gwangju Museum of Art is holding a media art exhibition entitled “Meta Garden.” There, I was walking through a virtual garden next to a stream, and I sat on a cube-shaped chair, looking up at the cube-shaped clouds and sky, listening to songbirds. I was amazed by the fact that this virtual nature was unfamiliar to me, but I could feel comfort in it. It made me want to learn more about the world of media art.

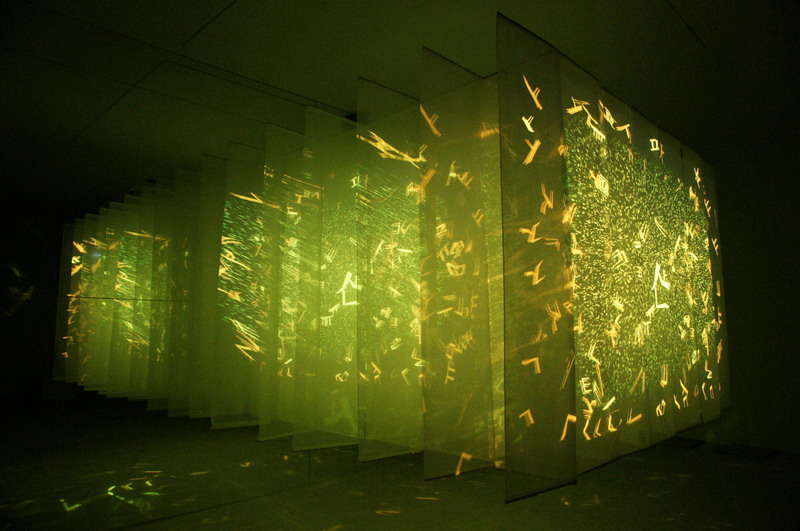

Media Artist, Park Sang-hwa

For this article, I interviewed one of the first-generation media artists who has long pioneered the path for media art. I visited the studio of artist Park Sang-hwa. He kindly explained what media art is by showing me the video portfolio that he has long been working on. Here is that interview.

Jennis: Thank you for your time, Mr. Park. I am a bit unfamiliar with media art, but I want to learn a lot from you. When and how did you get involved in media art?

Park Sang-hwa: I originally majored in sculpture in college. Sculpture is a genre that has curiosity in its methods of expression. We think not only about the materials, like metal, stone, and wood, but also about three-dimensional space when we work. It was very interesting for me to see graphic programs using computers, as was the trend at that time. I thought I could do a variety of visual experiments. So, I started exploring new media by creating works one by one.

Jennis: You said you were trying to change the method of creating artworks by using computers, so when did you start work in media art in earnest?

Park Sang-hwa: The first Gwangju Biennale was held in 1995. One of the main artists was Nam June Paik. He invited media artists from all over the world to come and hold a special exhibition. The title of the special exhibition was “Info Art,” and video artist Nam June Paik thought that anyone should be able to enjoy the arts – the most common medium in use by the public was the TV back then. It was shocking to me to see that things I had only imagined had already been created and displayed by world-class artists. That is when I started working in media art.

Jennis: Long ago, I saw a piece by Nam June Paik at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Gwacheon. It was a huge tower of monitors entitled “DaDaIkSeon” (다다익선), “The more, the better.” I was surprised at his use of the TV as a communicative medium for people all over the world. His experimental work “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell” was made in 1984. That time was so early for the popularization of the use of the computer as a communicative tool. I think Nam June Paik had looked far into the future.

And you said that you started working in media art just after the first Gwangju Biennale. Then you have been doing media art for almost 30 years! You must have had a lot of difficulties as a pioneer starting out on barren land in the field of media art.

Park Sang-hwa: Media art requires a lot of technology, and it was very difficult to obtain equipment and learn technology because it was a time when computer technology was not as advanced as it is now. So, the speed of work was very slow.

Jennis: When was your first exhibition of media art?

Park Sang-hwa: After a long period of preparation, my first media art exhibition was held in 1998, and the works in it had been produced over a number of years. But I had not turned completely into a media artist because I still used elements that I had learned as a sculptor. For example, I made my apartment as a sculpture and showed what was inside the windows using media art. To capture something between the spaces and to create interest in the substantive features are the characteristics of sculptors, I think.

Jennis: Do you make sketches and take photographs for creating your artwork? Or do you work with graphic design? I am curious about the process.

Park Sang-hwa: Most of the photos, videos, and sounds used in my works are taken, collected, and reprocessed myself. I usually observe my daily life and the nature surrounding me. Using computer graphic technology, I work on artistic imagination from my experience with the comforting and healing moments in my life.

Jennis: You have said that you sometimes work with a team named “Bibimbap.” I wonder how the team was organized.

Park Sang-hwa: Bibimbap was formed in 2011. The team members are from different generations, and majored in diverse fields: media art, computer engineering, literature, painting, dance, and music. We were a group with different cultural and social experiences, so we named ourselves “Bibimbap,” after the delicious Korean food with all those healthy ingredients mixed together. The Bibimbap team attempted the aesthetics of convergence through artwork we called “Mudeung Do-won-gyeong,” which was based on Mudeung Mountain in Gwangju.

Jennis: “Mudeung Dowon” – that’s quite interesting. It sounds quite similar to the ancient Chinese fable Mureung Dowon, which refers to an eternal paradise full of peach blossoms. So, you found Shangri-la in Mt. Mudeung. Perhaps that is why it was so fantastic to see fluttering petals in your work. What other attempts did you make in your early media artwork?

Park Sang-hwa: As I told you, my major was sculpture, so I tried to harmonize media art with sculpture. I wanted to express the value of life and the image of a self-portrait through video installed in sculpture. In 2000, I had an exhibition of 100 bags of rice piled up in a cubic shape, with some monitors between the rice bags. Playing on the monitors was the food-eating show Mukbang, in which they were eating hamburgers, pizza, chicken, and snacks. The title of the work was “Geurim-ui tteok” (그림의 떡, lit., rice cake in a picture), the idiom for something you want but cannot have. And a video of a hungry child was shown on a monitor hanging from the ceiling. I wanted to express the reality that there are people who are still hungry in the midst of a global wealth imbalance, and that at the same time, there are others who are worried about obesity due to overeating.

Jennis: You said that you usually observe daily life and your natural surroundings, and then incorporate them into your works. So, an example of this would be your apartment and the kitchen table, correct?

Park Sang-hwa: Yes. In the Apartment series, the table scene shows spoons and chopsticks flowing down below the table, similar to the Salvador Dali painting. I think the advantage of media art is that it can express successive moments, which is difficult to express in paintings. We live a repetitive life without any feelings of doubt about the real world surrounding us. I sometimes wanted to see myself from a distance and express what I feel in my imagination.

Jennis: Do you have any plans for future exhibitions?

Park Sang-hwa: I am presently exhibiting in the Jeonnam International Sumuk Biennale (수묵 비엔날레), which is being held until the last day of October. The 2021 International Ink Biennale will be held at Mokpo’s Culture and Arts Center, at Jindo’s Ullim-sanbang, in Gwangju, and in many cities in Jeollanam-do. I am exhibiting under the theme “Sumuk Without Ink, Sumuk Is Everywhere.” Traditional ink painting has begun accepting media art as a modern medium for the genre. Due to the coronavirus, the number of visitors at any one time is limited, so it is best to book online in advance.

Jennis: Well, congratulations on your ongoing work. I am interested in seeing how traditional ink painting, sumuk, can be expressed as modern media art. Thank you so much for your time.

After the Interview…

While covering and studying this relatively new field of art, I thought about the differences between technology and art. Art is concerned not only with the enjoyment of novelty but also with giving reason and emotion to humans. So, it occurred to me that media artists may be the key to opening up our private spaces, our personal matrixes.

Photographs courtesy of Park Sang-hwa.

The Interviewer

Kang Jennis Hyunsuk is a freelance interpreter who loves to read books and grow greens. She has lived in Gwangju all her life and is certainly a lover of the City of Light.