Making Filmmaking Personal: An Interview with Roberto Santaguida

Roberto Santaguida is a Canadian filmmaker working extensively in the field of documentary and experimental films. He completed his studies in film production at Concordia University, and his work has been screened at more than 400 international festivals, some of which are the Tampere Film Festival in Finland, the CPH:DOX in Denmark, the Contemporary Art Festival Sesc_Videobrasil in Brazil, Flickers’ Rhode Island International Film Festival in the United States, and Message to Man in Russia.

Among his notable works are Miraslava, Goran, and The Universe According to Dan Buckley, and he is the recipient of the K.M. Hunter Artist Award and a fellowship from Akademie Schloss Solitude in Germany. He has taken up artist residencies in numerous countries, including Romania, Germany, Norway, Australia, and Korea. At the moment, he is in Gwangju to present his latest exhibition at the Asia Culture Center (ACC), creating the opportunity and honor for the Gwangju International Center (GIC) to host his special Documentary Film Workshop in April, as well as for this interview for the Gwangju News.

Gwangju News (GN): First of all, thank you for making time for this interview. When we first met in person at the GIC, you asked me a very interesting question, so I would like to start by asking you the same one: What is your story?

Roberto Santaguida: My story is that of a hotel porter. You know, the one who knocks at the door and is asked not to enter. That person on the other side of the peephole in the corridor. On a good day, an extra, to paraphrase Stephen Malkmus, in the movie adaptation of the sequel to my life.

GN: Having in mind that the genre of “personal documentary” is something you are deeply involved in, is “What is your story?” the leading question when creating one? Could you explain for our readers in a bit more detail what a “personal documentary” is?

Roberto Santaguida: There is some disagreement, but fortunately the debate is not heated and has never disrupted a good night’s sleep, as far as I know. For example, I consider many avant-garde films to be forms of personal documentary film. In some cases, documentaries wielding standard devices like first-person narration are not necessarily personal. The argument is capped off with the certainty of an expiry date.

GN: Going one step back now, could you let us know why you have chosen documentary film as a medium to convey your messages and express your art?

Roberto Santaguida: If I could, I would be making flip books and thaumatropes, but I cannot draw. I do not hold any genres or subgenres in higher esteem than any others. I fell into documentary filmmaking during a moment of reconciliation, and I have never managed to extract myself. Fiction feature films remain a prime influence. I work in hybrid forms, so I fold in techniques whenever I find them.

GN: Your recent workshop at the GIC was also focused on giving insight on the genre of personal documentary and its creation to participants of various levels of expertise in filmmaking. What were your impressions of the workshop?

Roberto Santaguida: I am interested in simple gestures of camaraderie. Sometimes I watch bus drivers raise a listless hand in greeting to a colleague whizzing past on the other side of the street. That blur of fingers carries lots of meaning. To answer your question, the workshop was crammed with several such gestures.

GN: You have conducted similar workshops all around the world, both in person and virtually, for experts and beginners. During the workshops, of course, you share your experience and expertise, but I am guessing that working with various people in many different places and through different mediums would enrich your creative process in some way. What are your takeaways from such workshops, and why do you keep doing them?

Roberto Santaguida: My workshops are a latticework of dubious pedagogical methods, abandonware-type games, anonymous statements, and creative formalities. Leading workshops is an endless source of joy. Participants and I fumble around, and occasionally we reach a conclusion. Somehow, after not making sense for ninety minutes, we begin to find something in the nothingness.

GN: I have read one of your quotes online. It was “It is a documentary; it is not a non-fiction film” and found it very interesting since most people definitely associate “documentary” as a genre with facts and, therefore, non-fiction. Would you introduce your specific documentary style through explaining the statement?

Roberto Santaguida: While the statement hums with familiarity, I am not sure what I meant by it. I will take a guess. Once a filmmaker introduces editing, a documentary becomes less about facts and more about moments of recognition and empathy. Perhaps they are granted an allowance to make legend of the world?

GN: Since I am from Serbia, I cannot help but ask about the backstory of creating the documentary Goran. Could you please give us an overview of this project, as well as how it was received?

Roberto Santaguida: The choreographer and performer Saša Asentić and his organization Per.Art

invited me to Novi Sad to produce a film about one of their artists, Goran Gostojić. They hoped the film would confront and challenge preconceived notions and stereotypes. Ten sets of hands relayed the project to shore. When I started the production, I was lugging around a tote bag that bore my long-time bitterness and hostility. After meeting Goran, I forgot it on a bus.

GN: Moving onto the reason why you came to Gwangju this time, could you share some info about your upcoming exhibition at the ACC? What have you been preparing since last December? Let our readers know how they might be able to experience the project!

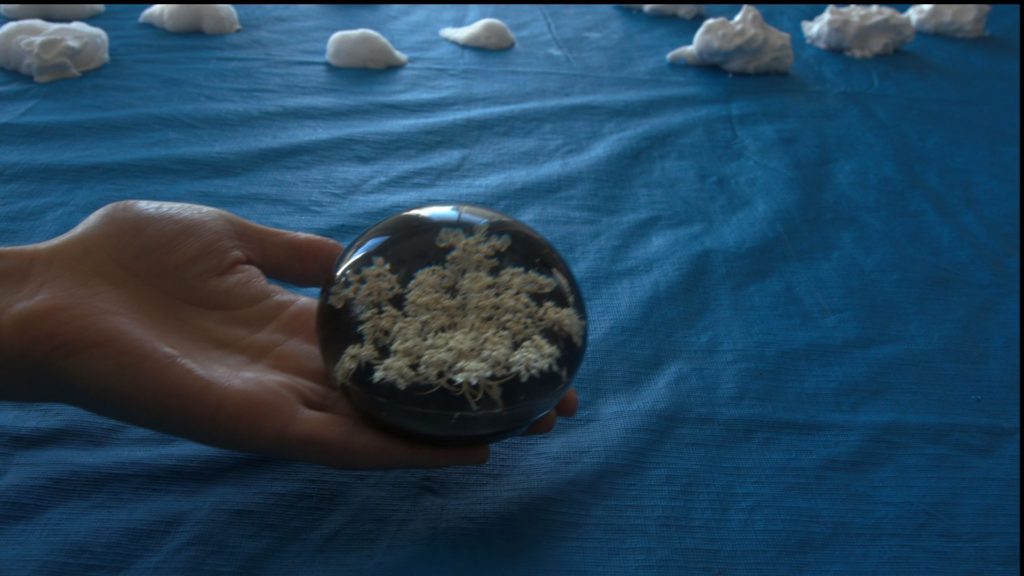

Roberto Santaguida: My exhibition at the ACC concentrates on the city’s waterways. On the other hand, the video is actually examining the marks that time leaves on the land, on the collective memory, how we document those traces, commemorate them, try to journal them, and suffer, silently, to live in the memory of our best days.

GN: What are your thoughts about Gwangju and Korea in general? Do you plan to come back in the future?

Roberto Santaguida: When I first arrived, I got lost in the city, on purpose, ignoring my map. I would wander down roads, reach a dead end, turn around, and start again. And even when winter was suffocating, and I did not know anyone, these solitary moments would resurrect me. In this way, the city and, by extension, the country have been kind to me.

GN: Do you have any final comments or thoughts you would like to share with our Gwangju News readers?

Roberto Santaguida: I want to express my gratitude to some people who either accepted my clumsy attempts at friendship or shared a spool of images I never would have imagined. In alphabetical order: Haryo Hutomo, Stella Jang, the two Yuri Lees, Arlo Matisz, Juhee Park, Irene Agrivina Widyaningrum, and Isaiah Winters.

Interview by Jana Milosavljevic.

Photographs courtesy of Roberto Santaguida.

The Interviewer

Jana Milosavljevic was born and raised in Serbia. She currently lives and works in Gwangju as a GIC coordinator. She loves exploring new places, learning about new cultures, and meeting new people. If you are up for a chat, she can talk to you in Serbian, English, Korean, Japanese, or German.