Interview with Top Reggae Archivist Roger Steffens

Interview by Isaiah Winters

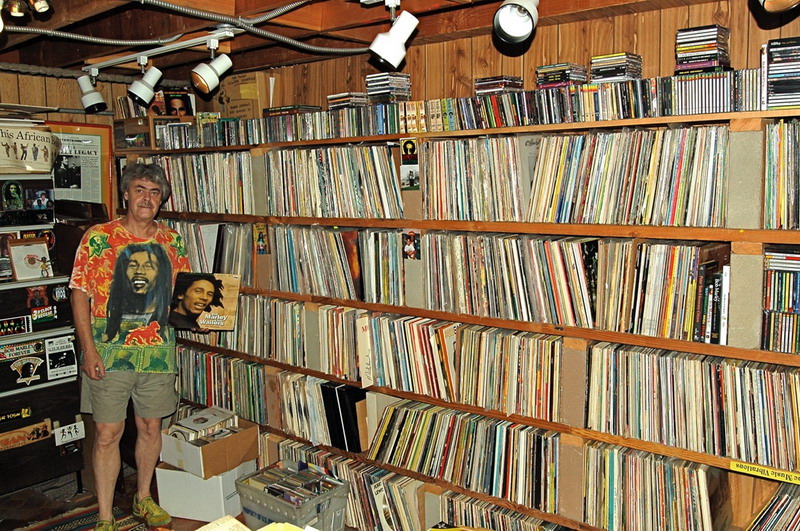

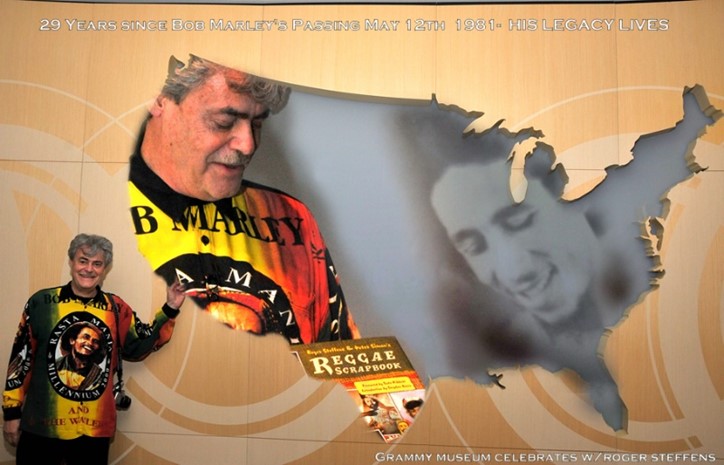

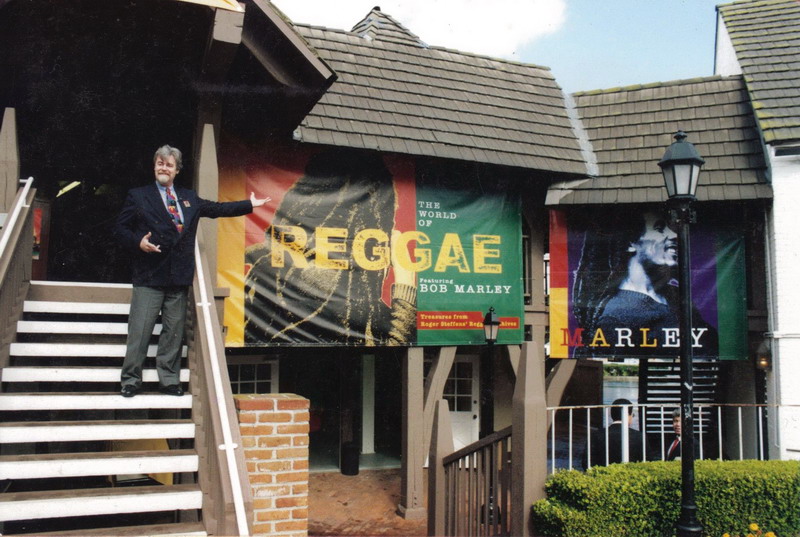

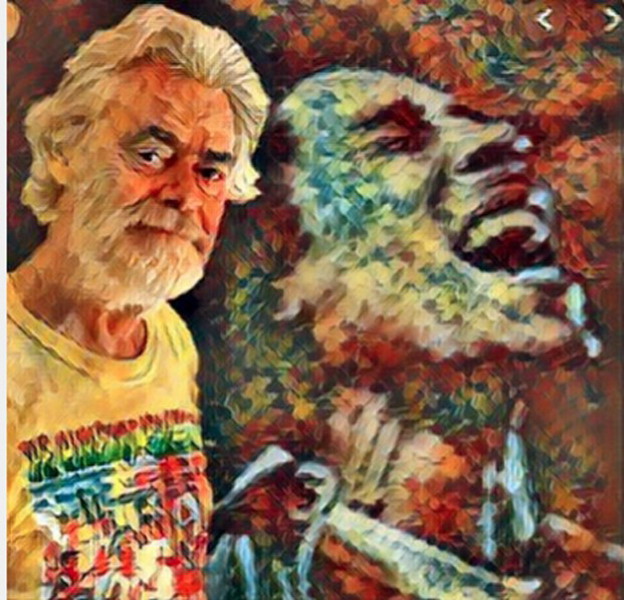

Featured at this fall’s Gwangju Design Biennale are the prolific works of actor, writer, lecturer, editor, photographer, and producer Roger Steffens. Lucky for us in Gwangju, his installation at the Gwangju Design Biennale’s International Pavilion (Hall 2) will showcase arguably his best-known work: extensive reggae music archives, with much focusing on the life of musician Bob Marley. I recently reached out to Roger for an interview, and he graciously responded despite the tight deadline. What follows is our discussion about his installation, his vast knowledge of reggae, the life of Bob Marley, and his outlook as a writer and photographer.

Isaiah Winters (IW): Firstly, thank you so much for taking the time to answer a few questions for Gwangju News readers. At this year’s Gwangju Design Biennale, you’re showcasing your reggae archives and so much more that you’ve produced and collected over many decades. For visitors who are unfamiliar with your work and reggae music, what do you hope they take away from the experience?

Roger Steffens: The knowledge that there’s more to music than dancing. Bob Marley said, “Dance to Jah music,” which means dance to music whose lyrics lift the soul and spirit of humankind. This is message music, music to instruct, inspire, and offer hope that a better world can be achieved if we practice the Rastafarian philosophy of One Love. That’s the name of Bob’s song that became the Anthem of the Millennium, known and loved by people in every time zone of this planet.

IW: Bob Marley, whose life you know better than most, got a rough start in music, often at the hands of shady producers who’d cheat him out of his rightful earnings. I suppose this is where a lot of his music industry cynicism emerged. What do you suppose Bob would think of the K-pop industry today, and of the current music industry more globally?

Roger Steffens: I think in some ways he’d be baffled and angry that oligarchs have taken over entire careers and bodies of work with only the bottom line behind all their decisions. Bob was cheated throughout his life, never earning more than two figures a week in his earliest days with producer Coxson Dodd, no matter how many thousands of records he was selling at the time. Accountants’ tricks robbed him of much of his later earnings. As a result, at the time of his final illness in late 1980, Bob was about to sign a ten-million-dollar contract with Polygram Records, hoping to establish his company as a Jamaican Motown, with artists owning their own music and its potential rewards. K-pop is an example of a country supporting a music that became one of the biggest financial bonanzas of our time. Bob would have loved that, but wouldn’t have allowed the capitalists to pull the musicians’ strings. He would have given artists control over all artistic decisions.

IW: One of the more fascinating details to emerge about Bob’s life is that in his later years, monthly some 6,000 people were financially dependent on him – meanwhile, he didn’t even have a bed of his own, let alone a house. Could you share with us another little-known fact of Bob’s life that sheds positive light on his unique character? Also, as he was just a man, what’s a little-known fact about Bob that sheds a negative light on him?

Roger Steffens: Bob wasn’t a saint, but there’s no question that much of what he did in life was saintly. As you say, he didn’t even own a bed until about 18 months before he passed. He supported that number of people because he believed he’d been sent to earth for a purpose, and that was to help his people in their quest to recover from 400 years of slavery and colonialism. He started businesses, bought farm equipment, and fought for the legalization of the herb. He gave away almost all of the money he made. His music is the rhythm of resistance embraced worldwide.

Although Rasta people are nearly all vegetarians, Bob did, in fact, on occasion eat meat. After his melanoma cancer had been discovered in the summer of 1976, he spent most of the following year in London, working on the albums “Exodus” and “Kaya,” and living with Cindy Breakspeare, the reigning Miss World, who cooked him liver to “strengthen him.”

As for a negative light, I’d say that Bob was very lucky to die when he did, at age 36, with his reputation largely intact. Twelve years earlier, he’d predicted the exact age he would die. He was at the absolute pinnacle of his success, filling stadiums all over Europe in 1980, when the notorious Shower Posse began to penetrate Bob’s entourage. Their intentions were most likely to smuggle drugs through Bob’s equipment, and it’s fairly obvious that that wouldn’t have gone undiscovered.

IW: In your Library of Congress lecture entitled “Oral History of Bob Marley,” you mentioned that there’s a surprising amount of rumor and conjecture surrounding Bob’s life. These include CIA involvement in the assassination attempt on his life, the source of his ultimately terminal form of cancer, and the “Nazi doctor” who treated him up until the very end. With so many relatives, friends, and other contacts still alive today, what do you think explains the persistence of so many rumors?

Roger Steffens: No one wants to believe that the obvious is most often the truth. Fans don’t want to believe that a man who advocated a healthy lifestyle – he ran miles every morning, played soccer every chance he got, had his personal i-tal (natural) cook on the road with him – could die at such a young age. The rumor that someone gave him a boot with a poison nail in it the day after he was shot in December 1976 is also utter nonsense. First of all, you cannot give someone melanoma. And it doesn’t arise from injuries. It’s genetic, and Bob’s white father’s family had a history of skin cancer there in Jamaica, and one death from melanoma. Nor has any concrete evidence of CIA involvement in the assassination attempt ever come to light.

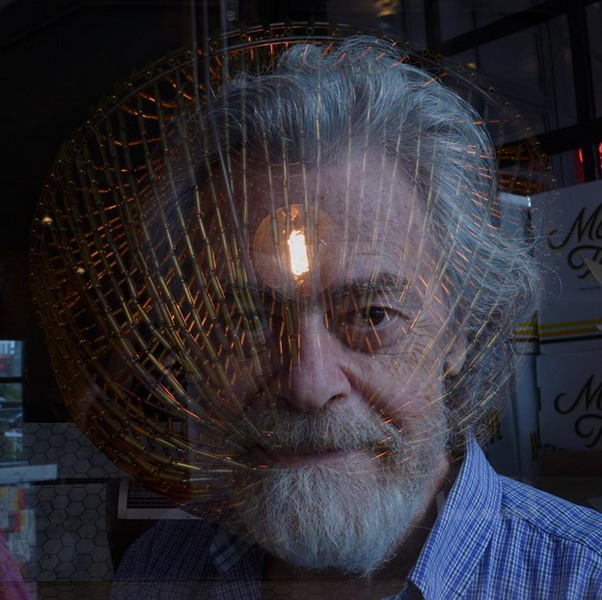

IW: Now turning to your prodigious works, you have over 50 years of amazing slide photography compiled online and in book form. Titled “The Family Acid,” it’s an evocative miscellany of heterodox images that any photographer can immediately appreciate. What things do you aim to capture when you’re behind the lens, and what advice would you give to aspiring photographers?

Roger Steffens: Good question. My designation as “photographer” came very late in life, thanks to my children, although I’ve been shooting all my adult life. When I was drafted and sent to Vietnam in the Army in late 1967, the first thing I did was buy a camera, because I knew I was in the middle of a historic event. So, I guess the first thing I wanted to learn how to do was find images that would represent the reality of living in Saigon at the height of the war, with no place truly safe. And the ephemera. Everything is ephemeral ultimately, of course, but there were things particular to war that could be gone in the blink of an eye. I carried my Canon FT everywhere from the DMZ to the Delta for 26 months, working with refugees, and returning home to lecture against the war in 1970, when students were murdered by National Guard troops and schools everywhere went on strike. I photographed the demonstrations from coast to coast.

For young photographers, I would suggest selecting a handful of themes you want to investigate. It could be as simple as fire hydrants, something you can find in virtually every country. My dear friend, the great war photographer Tim Page, shoots laundry everywhere from India to Kabul and outback Australia.

Rule number one: Never leave your home without your camera, and always bring an extra battery or two. Also, experiment. I’ve been shooting double and triple exposures since Nam. With the apps on cell phone cameras now, bizarre optical effects that would have taken weeks or more to create in a darkroom, are there at the press of a button. Learn them, free yourself to think “outside the box.”

I live in L.A., a city that destroys its history without compunction, so I have hundreds of tear-down-and-rebuild photo series, as landmarks become soulless concrete warehouses for people and products. I love to shoot the sidewalk stencils on Melrose Avenue and the ever-evolving murals, some of which are masterpieces that last just days or weeks. Enormous advertising posters for movies and TV litter the heights of Sunset Strip and are unique signs of the times. I’ve also taken to shooting gas prices, beginning in December of 1969 upon my return Stateside, where a Berkeley, California, station sported a sign that said “Gas – Cheaper Than LSD.” Gas was 19 cents a gallon then.

IW: At this year’s Gwangju Design Biennale, you’re featuring many of your written works, in addition to records, items, and prints centered on reggae music. You’ve written quite a few books focused on reggae music, a musical genre you found early on in life and developed an insatiable interest in. What do you think undergirds your writing success over the years and what guidance might you give first-time writers?

Roger Steffens: I’ve always written from the perspective of a fan who got lucky. I’ve been writing all my life and was fortunate enough to have mentors who were poets and perhaps gave me a style. I read poetry for years in a one-man show called “Poetry for People Who Hate Poetry,” and even had a program on TV in Saigon reading poetry to the combat troops on Sunday afternoons. That gave me a real feel for language. I didn’t publish my first book until I was 54, now I’ve got ten. But I had co-edited a magazine, The Beat, over a 28-year period, and was a voracious reader.

My first national piece was in 1970 in Rolling Stone, and I continued to contribute to periodicals, especially since the early 1980s, writing about my discoveries in the world of Jamaican culture and music. My first interview was with Peter Tosh, the second with Bob Marley. After that, anyone in the reggae world I approached knew that I understood when they spoke in patois, and had a grasp of the island’s fraught history. If you know your subject, you shouldn’t be afraid to talk to anyone. Show respect and understanding, and it’ll truly open doors. Follow your passion, the thing that makes you want to get out of bed in the morning to tell your friends about. And never stop learning.

IW: Finally, what topics do you think a young Roger Steffens would be obsessed with in 2021? Also, where might a young Bob Marley be today?

Roger Steffens: I made the bulk of my income since moving to Hollywood in 1975 from voice-over work. In Forrest Gump, I’m the announcer in the White House when he goes to visit Pres. Kennedy and has to pee so badly. Today, I think of how much easier it is to do voice work from one’s home for clients anywhere on earth. I don’t have to waste gas driving to far-flung auditions, and things can be turned around in an instant. I might be more interested in film production. There are always new forms of art to be discovered, new songs to hear, and pieces of the past that finally surface after decades of suppression, so the thrill of the new is still possible if one is open to them. My motto has always been “Aim High.” And never be discouraged by naysayers. As Joseph Campbell advised, “Always follow your bliss.”

As for Bob’s youthful successor, I don’t think he/she has been discovered yet. Every generation needs its own spokespersons to reinterpret the eternal truths for their contemporaries. It might be some biracial inhabitant of Gwangju helping bring an Asian overstanding to the rest of the world. I’m ready to listen.

IW: Thank you again for your time. I can’t wait to visit the Gwangju Design Biennale to see so much of your life’s work in person.

Roger Steffens: Thanks for taking the time to speak with me. One Love, everyone.

Photographs courtesy of Roger Steffens.

Gwangju Design Biennale

Venues: Gwangju Bienalle Exhibition Hall, Gwangju Institute of Design Promotion, Gwangju Museum of Art

Dates: September 1 – October 31

Website: www.gdb.or.kr

Email Inquiries: bob0328@gdb.or.kr

Ticket Purchase: http://www.ticketlink.co.kr/product/34859

The Interviewer

Born and raised in Southern California, Isaiah Winters is a pixel-stained wretch who loves writing about Gwangju and Honam, warts and all. When he’s not working or copyediting, he’s usually punishing himself with long hikes or curbing his mediocre writing and photography with regular practice. Regarding the latter, you can check his progress on Instagram @d.p.r.kwangju.