Painter of “The Wind Flows Among the People”: Yoon Nam-woong

By Kang “Jennis” Hyunsuk

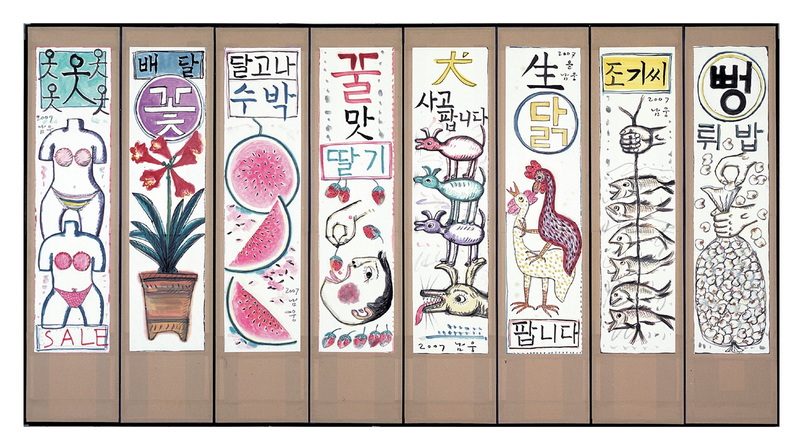

Daein Market

The place where I first met Yoon Nam-woong’s artworks was at Daein Market in downtown Gwangju. When the old market, where I used to go grocery shopping with my mom as a child, was gradually emptying out because of the newly emerging shopping malls, young artists came into the vacated shopping areas and created their own work spaces. One by one, small, unique galleries were created like nothing I had seen before, and people began to visit Daein Market to see their artworks. I remember that “The Arts Market” was opened every weekend and that my family also went to Daein Market to enjoy the various artistic works as well as the fresh foods.

I remember us sitting on street chairs and asking one of the artists to paint our portraits on paper with indigo ink. It was a good memory. For this issue of People in the Arts, I introduce the artist who played a major role in transforming the Daein Market into the Daein Art Market. This artist, Yoon Nam-woong, gave lots of joy to the visitors of the Daein Art Market with his witty and humorous artworks. I heard that he returned to his hometown in Jindo a few years ago. Thanks to the Gwangju Museum of Art, I was able to contact him and visit his studio in Jindo for this interview.

The Interview

Jennis: Thank you for allowing me to do this interview for the Gwangju News.

Yoon Nam-woong: Thank you for coming this far from Gwangju.

Jennis: When I entered the village, I could guess that this extraordinary building standing tall on the hill was your studio. Is this your hometown?

Yoon Nam-woong: Yes, this is where I was born. As you know, in Korea, there was a custom of burying a baby’s umbilical cord when it was born. My umbilical cord was buried over there. I was born here and went to Jindo Middle School and Jindo High School, so I never left here before going to university.

Jennis: In Jindo, the Unlim Sanbang art house has been famous for oriental paintings for generations. Many people visit the place from all over the country. Did you have any connection with the Unlim Sanbang?

Yoon Nam-woong: None. Oh, when I was in my first year of high school, my brother bought me a book of paintings by the artists of the Unlim Sanbang as a gift before he went to the army. It would be the only relationship between the Unlim Sanbang and myself. I think I was never influenced by the traditional paintings of Jindo.

Jennis: You graduated from Chonnam National University’s College of Arts. When did you start painting, and how did you prepare to enter the College of Arts?

Yoon Nam-woong: Painting, for me, came naturally. I liked painting from an early age, and the calligraphy I learned in art class at school was also interesting, so my father was proud of me when I sat on the floor and did calligraphy with my ink brush. My father was a farmer, but he learned Chinese characters while attending a traditional village school or seodang (서당), so he could read newspapers, which were rare in the countryside. The newspapers at that time were written almost entirely in Chinese characters, so I learned Chinese characters from the newspapers and tried to write them with a brush and ink. When I was in art class in middle school, my art teacher saw my artwork and encouraged me to join the art club, so for my six years of middle and high school, I drew and painted as a member of the art club.

Jennis: You entered Chonnam National University in 1983. What was the university atmosphere like at that time?

Yoon Nam-woong: At that time, the vestiges of 5.18 [the Gwangju May 18 Uprising] remained all over the campus. We sat in makgeolli bars longer than in the lecture room. I majored in ink-and-wash painting, but the elite-oriented university education and “art only for the sake of art competitions” did not interest me. I thought I should be able to make my own paintings after reaching the age of twenty. So, it was hard to adapt to the apprenticeship learning system for oriental paintings that consisted of identically copying famous artists’ paintings. But I made friends who had the same worries, and I think I was able to get started at painting thanks to those old friends. Though we argued fiercely at times, through this, we guided each other on the tough road of art when our future was vague and blurry. So, when I go to teach young art students, I encourage them to make friends with others like themselves.

Jennis: What was your life like after you graduated from the College of Arts?

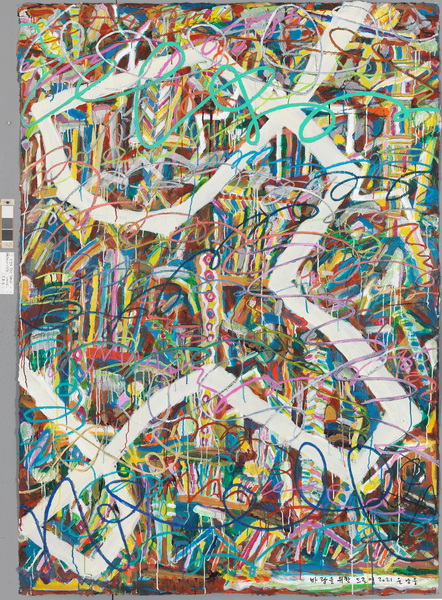

Yoon Nam-woong: When I was 29, I rented a village warehouse in Damyang and lived alone like a wild dog for about three years. I sometimes went to the village cemetery with my painting paraphernalia. One day I saw that the mountains were bare because the pine trees had gotten diseased and had to be cut. That lead me to paint the True Colors of Terra. I wanted to express the color of the Jeolla region, the sentiment of this land. In fact, a boat floating on a calm lake and the old Taoist walking along a path with a cane in oriental paintings have few connections to our present lives. I wanted to depict the culture around me and my life with my art. I had my first exhibition with the True Colors of Terra in black ink and clay water. Thankfully, many people visited and liked my paintings.

Jennis: How were you able to use clay water as one of your materials?

Yoon Nam-woong: At the time, there were no paints available containing natural mediums, so some artists used to experiment with diverse mediums in their painting, myself included.

Jennis: After your first successful exhibition, you went to China to do a master’s program in art. What made you decide to go there?

Yoon Nam-woong: From the time I graduated from college, I had a thirst to know more about the society in which I lived, and I thought that I would need to study something different to mature my thoughts and skills. Luckily, the diplomatic relations between China and Korea had just been established at that time. I went to China to see Chinese realism art, their ink-and-wash paintings, Chinese calligraphy, and their art of character carving. I studied at Lu Xin Art School. As Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, former leaders of China, finished the Long March, they entrusted the creation of an art school to the art team that had been engaged in cultural movements during the Long March. So, the art school, named after the famous Chinese writer Lu Xin, was established. Starting with basic drawings, I had the opportunity to broaden my perspective through academic classes and various materials presented by professors. However, I was still constantly concerned about my paintings, pondering how to express the culture of my own birthplace to carry me through life.

Jennis: What has changed in your paintings since you came back from China?

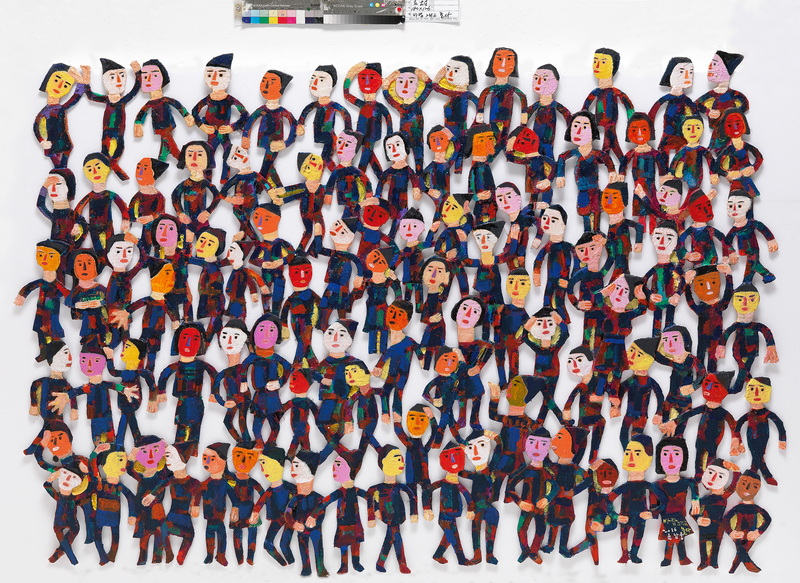

Yoon Nam-woong: I had the studio in Damyang and still spent my time thinking about my paintings. What was different was that I started to put people in my paintings instead of doing landscapes. On a late summer day, I was walking along a stream, Gwanbang-cheon in Damyang, and I saw several young men of the town sitting under a tree, drinking coffee from a tearoom delivery girl. I saw them from across the stream. I felt how blithesome life could be and painted the scene, which I named Song of Gwanbang-cheon. The change in my paintings began with this painting. Some people might say my paintings are third-order art.

Jennis: Song of Gwanbang-cheon reminds me of Kim Hong-do’s traditional genre paintings that featured everyday lives of people in the Joseon Dynasty. I wonder why you say your artworks are like third-order paintings?

Yoon Nam-woong: Third-order things are those that have already passed by us. When we were young, jjajang-myeon (짜장면, black bean-sauce noodles) was a much-awaited treat, but now it is just a so-so meal. Like jjajang-myeon, there are so many things that have left our daily lives. But I want to bring back memories with my artistic language using the five senses. I think that third-order paintings can be quite progressive and innovative, focusing on culture that the public can enjoy rather than that elite culture that only a few can actually enjoy. I just hope people can enjoy my paintings.

Jennis: I was delighted when I saw your witty works in the Daein Art Market. How did the Daein Art Market come into being?

Yoon Nam-woong: The art market of Gwangju was small at the time. So, I put into practice the idea of bringing cultural democracy to the art community in Gwangju with my friends who had also been concerned about it. One goal was to allow anyone to express themselves freely about 5.18 in Gwangju [which was stifled at the time], and another was to release the artistic sensibilities of young artists on the streets of Gwangju. The Daein Art Market was a revolutionary art space, the likes of which are hard to find in the annals of Korean art history.

Jennis: What made you go back to your hometown, in Jindo?

Yoon Nam-woong: There were many things that occurred after the Daein Art Market. Suddenly my wife became seriously ill, and I hurried back to my hometown, seemingly running away from so many kind people around me. I built this studio and house for two purposes: to take care of my wife and to work as a farmer and artist. And this year, we had our first successful harvest of peaches and figs in four years!

Jennis: What do you consider art to be for you?

Yoon Nam-woong: I remember when my grandmother passed away; we sent her on her way with a traditional funeral. The funeral bier was decorated with white paper flowers and some small wooden dolls. The bier singer led the chant of the funeral march with ringing bells. Within the sadness, beautiful majesty was clearly etched in my mind. The villagers who led the funeral were not professional artists by any means, but they all performed artistically for their departing neighbor. I came to think that art is not very far away from our daily lives. I think that art is always with us, contained within our reality.

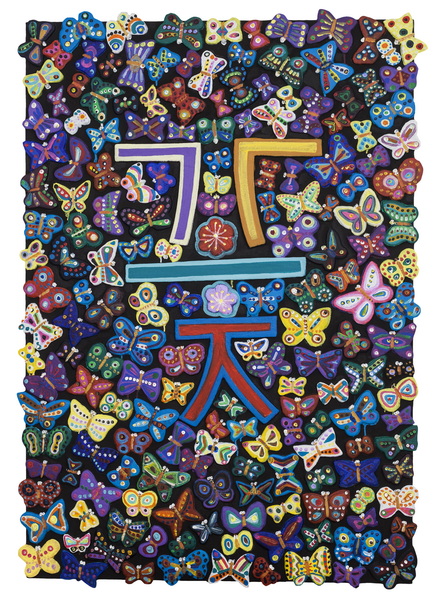

Jennis: I saw a pile of calligraphy paper in your studio. What kind of relationship can there be between calligraphy and oriental painting?

Yoon Nam-woong: Oriental painting and calligraphy are very similar with respect to brushwork. In calligraphy, it is important to understand and create harmony between letters or characters. Sometimes fast and sometimes slow, the brush stokes have rhythm in calligraphy. And this is also true in oriental painting. Calligraphy is an attractive artform in itself, but I think it is a very important foundation for oriental painting. I often do calligraphy these days while thinking about what words would touch the hearts of people today.

Jennis: I think you have your own style of painting that no one can imitate. I believe you will soon have new artworks to show us.

Yoon Nam-woong: Now, I am getting used to working as a farming artist. I will work hard for the next two years, and I want to invite you to my next exhibition.

Jennis: Thank you! I will be eagerly waiting for that exhibition invitation, and I thank you for this extensive interview.

After the Interview…

Like coffee and wine, all crops have different scents depending on the soil they grow in. People can also be said to have their own scents, depending on the “soil” they live in. Artist Yoon Nam-woong is maturing his thoughts on painting in his hometown now. Throughout his The Wind Flows Among People series, he tells us that we are all connected by the wind in the air. And through his artworks, I could also read his respect for the common folk. I am sure he will soon show us another distinctive scent in his paintings.

Exhibitions

- 2022. The 30th Anniversary Exhibition, Second Spring, Gwangju Museum of Art

- 2022. Puppet for You, Dongguk Museum of Art, Gwangju

- 2022. Seeing Again, Boseong Art Hall, Boseong, Jeollanam-do

- 2021. The Shadow on the Water, Baekmin Museum of Art, Boseong, Jeollanam-do

- 2021. Island of Wind, Solmaru Museum of Art, Jindo, Jeollanam-do

- 2021. The Hope for Opening the World, Catholic Archdiocese of Gwangju

- 2019. Delicious Art Museum, Gwangju Museum of Art

- 2017. Local Bus, Ha Jung-woong Museum of Art, Gwangju

- 2017. Microscopic Description, Oh Seung-woo Museum of Art, Muan, Jeollanam-do

Main Collections

- Jeonnam Provincial Museum of Art

- National Museum of Contemporary Art

- Hampyeong County Museum of Art

- Gwangju Museum of Art

Awards

- 2005. Excellence Award, Gwangju MBC Ink Competition

- 2003. Grand Prize, The 6th Gwangju New World Art Festival

The Interviewer

Jennis Kang is a life-long resident of Gwangju. She has been doing oil painting for almost a decade, and she has learned that there are a lot of fabulous artists in this City of Art. As a freelance interpreter, her desire is to introduce these wonderful artists to the world. Email: speer@naver.com