Learning Korean: The Adventure Continues

By William Urbanski

Well, well, well. It is once again that unfortunate time of year to reflect on my Korean language progress. All those years ago when I first started learning Korea, I had no illusion that Korean would be an easy language to learn, but given my background in foreign languages, I figured it would take no more than three or four years to become fluent. Fast track a bunch of years and while I have not thrown in the towel by any means, certain realizations about Korea, language learning, and some other stuff in general have made me come to terms with the fact that native-level fluency, maybe, is not such a great goal after all.

Hurdles of All Shapes and Sizes

As anyone who has looked into the matter surely knows, there are a couple of objective factors that make Korean a bit of a tough nut to crack, and in no particular order, here are a couple of the big ones. First of all, Korean is obviously in a different language family than English and works differently than Indo-European languages. While there are a large number of loanwords, it can be tricky to use them in a meaningful way. Then, there is the whole hornet’s nest issue of honorifics, which is kind of neat I suppose, but takes up a lot of bandwidth to not horribly offend people every time you try to say hello. Another interesting characteristic worth mentioning is that while anyone who speaks English grows up with a great deal of exposure to people speaking English with different accents, Koreans are much more homogenous in this regard, meaning that unless your pronunciation is pretty bang on, it may be difficult to make yourself understood. Things like different grammar and pronunciation are surmountable hurdles but require a disciplined and deliberate approach.

Besides the scientifically verifiable and objective features of the language itself, there are a host of other issues I would dub “situational factors” that add a layer of difficulty and complexity to learning Korean. Now, I cannot take credit for noticing all of these, but some of the major ones are outlined here. The first is the fact that so many people come over here as teachers: a position that, well, requires us to be speaking English most of the time. Every school that employs an expat teacher is slightly different, but I have experienced quite a wide range of, shall we say, “tolerance” towards speaking Korean during work hours. Most of my schools have been very welcoming of my interest in learning Korean, but some places have basically said to not use Korean at all (a silly rule that accomplishes nothing and one that I also flouted at every available opportunity). Another social factor that I would highly doubt I am alone in observing is the tendency for Koreans to reply in English, or start talking in English when you speak to them in Korean. There are myriad reasons for this, such as the fact that most Koreans are very eager to try out a skill they have spent years honing at school and the fact that it could be regarded as a polite thing to do. The reasons for this are not particularly important to understand here, but this is in stark contrast to, say, France, where the rule of thumb could be summed up as, “You are in France, speak French.” The sum of these and many, many other social factors means that on top of the typological considerations, the average expat/foreigner actually has surprisingly few opportunities per day to practice Korean in a meaningful way.

So yes, as you can see, it is not hard to dream up a laundry list of reasons why it is hard to get good at speaking Korean, but doing so actually obscures an important fact: Many people from all walks of life accomplish that very goal each and every year. Focusing on the reasons (real or imaginary) why Korean is so tough is actually somewhat counterproductive, as they are quite general and unspecified when effective language learning is a task that should be extremely personalized and very specific. To borrow a bit of parlance from Jordan Peterson, we could say that when it comes to language learning, focusing on social factors is “low-resolution” thinking and the path forward should be “high-resolution” and extremely specific. Identifying difficulties and learning through mistakes should not be an end in itself but rather a tool to change learning strategies and forge ahead in a better way.

Mistakes and Dead Ends

Speaking of mistakes, there are two major ones I have made (so far) when learning Korean: trying to memorize hanja and using flash cards. Years ago, partly because of a general fascination with the way Chinese characters are used, I got the bright idea that burning a ton of time trying to memorize hanja would be even the least bit useful. I even went so far as to buy a practice book, complete with cute little pictures and endless pages of grid paper (hanja are supposed to “fit” into an imaginary square box) on which I could carefully write each character, using the proper stroke order, of course. I even dabbled in those “four-character idioms” you may have heard about. I kept at this for a solid eight months or so and, in the end, had exactly jack squat to show for my efforts because the truth is that while many Korean words “come from” Chinese, a knowledge of the characters is not essential in the way it is for Mandarin or Japanese. Hanja, while definitely cool to know a thing or two about, just are not essential on the road to high-level, day-to-day proficiency, much the same way that knowing calligraphy will not make someone a better English speaker.

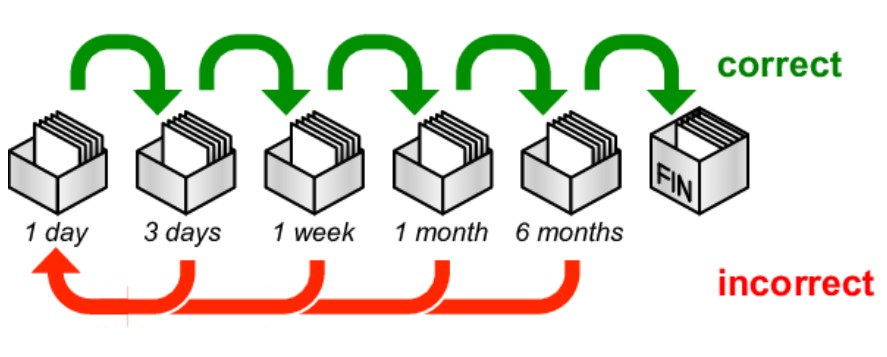

My bumbling and farcical extended encounter with hanja pales in comparison to the colossal, blundering waste of time surrounding flash cards that extended over roughly a thousand days. During this time, I amassed a literal shoebox full of thousands of handmade, painstakingly handwritten flashcards, 99 percent of which contained single vocabulary items. Using the Leitner system (which is actually pretty neat), I memorized an exhaustive quantity of lexical items… that I could not use effectively in sentences: a completely pointless ability for an agglutinating language. While this approach kinda, sorta, maybe gave me a half-decent foundation of vocabulary, in the long run, it amounted to spinning my tires.

The Way Forward: What Works in Gwangju

In short, what works when it comes to learning how to use any language effectively (as an adult, anyway) could be summed up in the following steps: Get a solid grammatical understanding of the language (how to conjugate verbs, use prepositions, etc.) as well as a solid base vocabulary (from five hundred to a thousand words), then practice with native speakers as much as possible. Fortunately, Gwangju has a slew of resources to help you accomplish both of these objectives. The Gwangju International Center is a great place to start with face-to-face classes. As well, there are other Korean “academies” around the city that I will not mention by name here but that I have heard nothing but good things about. While I think face-to-face classes are the best, especially at the early stages of learning, another option, which I have been using lately, is Talk to Me in Korean, a website that has actually pretty good lessons – the only problem being that you have to be very disciplined and motivated to slog though the massive collection of lessons that are more or less all identical.

As for step two (practicing speaking), how about making some Korean friends and buying them a cup of coffee? Ask to practice Korean with them for 20 minutes whenever you meet. There are also language exchanges happening all over town, especially at the GIC. “Practice Korean” is a pretty broad term, but another great way to go about this is to read short stories or books in Korean, preferably with the help of a Korean friend. For example, read the book out loud and have a friend correct your pronunciation. The added benefit of this approach is you can choose books or stories (or articles) that are in line with your interests. If you like soccer, read an article about soccer! When it comes to practicing Korean, try a bunch of things and do what works for you – in the end, any good language program should be very specific, and there is no one-size-fits-all approach.

Reassessing Goals

As a native English speaker, I always kind of assumed that the ultimate goal when learning a foreign language was, like some sort of James Bond-esque spy, to be able to blend in unnoticed among the speakers of a language. While definitely cool if you can do it with French, German, or Italian, when it comes to Korean, that is actually a really poor goal. If you were not born to at least one Korean parent and raised in Korea, no Korean will ever in a million years believe you are one. So for me, instead of trying to be some sort of linguistic chameleon, a better strategy is to be “a foreigner who speaks Korean pretty well” and who can go about my business with minimal difficulty whenever I am galivanting around the country.

So, what do you guys think is the best approach to learning Korean? Let me know in the comments below, and do not forget to like, subscribe, and hit that notification bell – it really helps the magazine.

See you in the next episode!

The Author

William Urbanski is the managing editor of the Gwangju News. He is married and can eat spicy food. Instagram: @will_il_gatto