Never Bored with Board Games!

By Ingrid Zwaal

At a recent workshop of the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter of Korea TESOL, the invited workshop presenter was Ingrid Zwaal. Her workshop was on using board games in the EFL classroom. Her presentation was interesting, informative, and full of tips (using a coin instead of a die). If fact, it was so useful that we have asked her to write this piece about board games to reach a wider audience. — Ed.

Games have always been a part of my life. Under the Christmas tree, we would find craft kits and games, mostly board games. My sisters and I spent hours playing these games. We played these games for more than to prevent boredom and give my parents’ some space: My parents were immigrants to Canada, and we used these games to learn about the society we were growing up in. We learned a variety of skills through some of these games – snakes and ladders for counting and fate, Monopoly for real estate, the memory game for how to quickly memorize where the different cards are, among other things. My mother made up games for us when we were doing chores, and my sisters and I made our own games together when we got older. The last time the three of us were on a three-hour road trip, one of them hosted a “name that tune” game she made for her senior patrons at the public library.

Think about your education, if you can remember back that far. Kindergarten was full of games and songs to teach you how to do things. I can remember Grade 1, when my teacher made sitting up straight to answer questions in class fun and exciting. She taught us to behave and be quiet through games like this. I even remember us crowded around each other, trying to barely breath so we could hear a pin drop. I swear I heard it. When did we stop making class and learning a good time?

I have not grown out of games. In university, I started playing Dungeons and Dragons, and I still do. On my own, when I am bored, I make up my own challenges and games to keep myself motivated. And I feel the same way when it comes to class. Sure, learning is a serious business and we charge for classes, but are learning and fun exclusive from each other? I started teaching in a language academy in 1994. Although we had a book to follow, most Fridays saw my adult classes doing other activities or playing hot seat. The internet was barely a thought then, and I had to come up with games more useful or exciting than hangman. Then I was given three children’s classes. Getting the kids to study for tests was an impossible task. Out of my own frustration, I began to give the students and myself a break by playing games on Fridays. It is not easy to come up with new answers every week, so I started to use the grammar and vocabulary we studied all week for the Friday games.

Then something bizarre happened: Students started to come an hour early on Fridays and had their textbooks open. I sent my assistant over to see what they were doing. She said they were studying. “Oh, for a test in school?” “No, for our class.” I looked at her. “Seriously?” “Yep.” My students were studying so they could win the games. Motivation. They were actually learning. Well, I guess they were excited enough to tell their parents, and then I was told no more games. I actually had a master’s in education. I rejected the school’s and the parents’ demand. I was not about to stop doing something that made them study and made my life easier. I told the kids that from now on the only thing they were allowed to say about Fridays was “grammar activities.” I got two thumbs up from parents, even though the students were doing the exact same thing. They saw their kids’ grades improve at school.

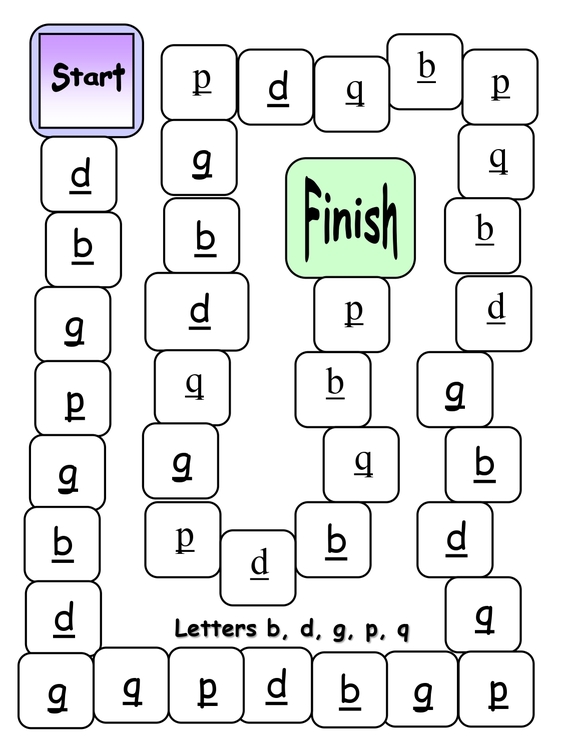

I moved to a university in Gwangju, where I was given children’s classes in addition to university classes. But they had a budget, and I was given phonetic and alphabet board games to use in class. The board games divided the alphabet into six parts and repeated the letters over and over again. We practiced the names, the sounds, and the colors on the squares. The kindergarten students were learning the names and sounds quickly and happily. Then I got a new student who agreed (with a ton of pressure) to try the class, and if he did not like it, he could take taekwondo the next month instead. He sat in a corner with his arms crossed in front of him, determined not to learn. If I asked him a question the only response he would give was “green.” So, “Mr. Green” sat away from the other four students, but when we played the alphabet board game, he became intrigued and asked the students if it was fun. They enthusiastically answered him. He moved closer. I offered him a token, and he started playing the board game. Soon he was participating in class. He left at the end of the month – hey, games and I are not miracle workers – but we did sucker him into trying for a while.

I moved on to teaching students who were going to become elementary school teachers. I started to provide games (activities that have winners) to teach them grammar and later games for them to use to teach their future students. My senior English department students started making games that we put in a book for the students to take with them based on specific lessons in the elementary students’ textbooks and later worked on how to teach these activities in class. Some former students have visited me after entering their teaching careers and have told me how important these books had become in their teaching.

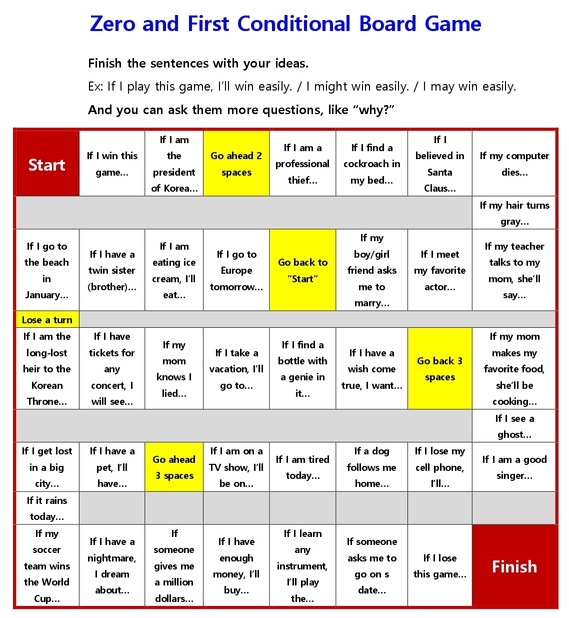

Now, I teach daily conversation classes at a different university to mid-level students. We went from a two-hour class once a week to three hours a week. Suddenly, I did not have enough content. I did not like the price of the designated workbook for the amount of work in it. So, I incorporated the textbook and workbook exercises into a lesson on PowerPoint slides and made worksheets to be done individually so that the students would get some practice thinking through the grammar. In the second weekly class, I assign another worksheet; this one is a little more difficult than the first. The rest of the class consists of activities. There is not a board game every class. I make other activities, like find someone who…, a card game, or matching sentences, often things that force the students out of their seats and in order to interact with each other. But the easiest thing to make is a board game, and there is always a potential winner, especially for the topics that do not easily lend themselves to other activities.

Why should we play games in class? Most students enjoy competition. It gives them a chance to talk and share in class. Most of my classes have students from different departments, and they do not know each other. Answering questions is a way to share and meet new people, and to get them talking for a reason. They can get help from each other, so this is an opportunity for cooperative learning. Some teachers swear that students are comforted by routine, but what is wrong with a change of pace? When did learning become so serious? I want my classroom to be a place of fun and laughter, but my standup routines do not always kill because of culture and language – so the games will have to do. But the students are practicing the grammar and vocabulary we had just studied in our lesson – sometimes they even look up additional vocabulary, without complaint. They practice some of it over and over in certain games, so in this way, we have returned to “listen and repeat” exercises without complaints or eyerolling, but with actual enthusiasm.

After I am sure they are used to playing the game, I usually join in. This usually is framed as a punishment at first, but the students seem to love it. It gives them a chance to try to beat me and to talk to me casually. I do not need to police them to make sure their answers are perfect every time. Most native speakers do not use perfect English all the time, either. Competence comes with confidence. If the students enjoy my class, my stats go up because I get better student reviews and a waiting list to get into my class. But the primary reason for playing games is “I want to have fun.” If I am bored in my class, I have failed as an educator.

Board games are easy to make once you have a game template. Copy someone’s, buy it off the internet, or make your own by making a grid and then making some lines invisible. They can be as complex or as simple as you want. You can use some of the same questions in the board games that you used in class or similar ones, “borrow” questions from other sources, or get super creative and ask more personalized questions. You can also use pictures for students to recognize and then use the vocabulary they were supposed to have memorized. Make one board for four to six students. Then photocopy it. I laminate the board if it is complicated, but the first time I use simple boards. I do not laminate them at first because after the students play each game, I find my mistakes or come up with better material. Then, after making the fixes, I laminate them.

One more thing: Add chance spaces. This gives lower-ability students a chance to win and gain some confidence. The standards are (a) go back to “start,” (b) lose a turn, (c) roll again, (d) go back two squares, and (e) go ahead one square. If students make a mistake, I only make them go back one square so that they can still feel some success. Otherwise, some of my students might never move! You also need dice and one token per student. I used to depend on students to have an eraser or use jewelry as a token, but I cannot seem to count on them to bring things, so I have a box with little colored plastic magnets or animal-shaped erasers that I hand out with the board games as well as one die per group. I buy these things at stationary stores or Daiso. If I want to slow down the game, I use 100 won coins instead of a die. The head side is “move one space,” the 100 side is “move two spaces” (two zeroes). I provide the coins because most students do not carry coins anymore. No, nothing has ever disappeared. Yes, there are many dice apps for cellphones, but I am trying to get the phones out of their hands. So, buy the dice; they are cheap.

When I made board games for children, specifically the letter and phonetic boards, I chose only five to six letters for a board and repeated them. The repetition helps them to memorize the names or sounds. I did the same with pictures for vocabulary. But I can reuse the letter boards and use them for words that start with certain letters; one-, two-, or three-syllable words; nouns; verbs; and plurals, and I color in the squares to use them to teach colors. When you put in the letters, always underline them so that p, d, q, and d do not get confused. And be careful with a and a, and with g and g. Always use lowercase letters, because we use them the most.

For older students, I encourage them to develop further after they get used to playing. After someone has answered a question, anyone can ask additional questions if they want. Sometimes games become conversation starters, and I think that is great. If the students never finish the game because they are talking so much in English, then my work is done. And instead of answering a question, the person who landed on the square can ask anyone in the group that question, but no one has to answer more than two questions in a row from the board game. I use personal questions within reason. Do not use yes/no questions on the board because the students tend to provide the shortest answers possible. I try to ask things they may want to talk about. I feel that the use of board games is pretty successful because most students do the worksheets without too much complaint. This is because they have realized that doing the sheets will help them win the board games. They win the board games, and I win at teaching because they actually learned. And you cannot beat that!

Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL Upcoming Events

- February 11, 2023: Monthly Workshop (at GNUE)

- Presentation: How Should Phonics Be Taught, and to Whom (T. Wyatt)

- Super SwapShop: Back-to-School Bargains, According to Teachers

Check the Chapter’s webpages and Facebook group periodically for updates on chapter events and other online and in-person KOTESOL activities.

For full event details:

- Website: http://koreatesol.org/gwangju

- Facebook: Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL

The Author

Ingrid Zwaal is a professor at Jeonju University with almost thirty years of experience teaching EFL in Korea. She is an officer in the Jeonju-North Jeolla Chapter of KOTESOL and has been a board game enthusiast for many years in and out of the classroom.