English in Korea: A Look Back

Written by Dr. David Shaffer

Originally published April 2013 #134

The year was 1971, Park Chung-hee’s Third Republic, and Kim Daejung had just shocked President Park by almost beating him in the presidential election. It was then that this writer came to Korea and began to witness the many changes that have taken place in all facets of Korea. Not least among these have been the changes that have occurred in the area of English education, aspects of which are the topic of discussion here.

English, English Everywhere

English, in its written form, at least, seems pretty much ubiquitous in Korea. A walk through Seoul’s Myeongdong district will quickly confirm this. It is quite difficult to find a storefront sign that is not in English. Brand names, whether foreign or Korean, appear in English. This was not the case forty years ago. Then, the same Myeongdong area sported an English sign here and there. Many signs were in Hangeul, but many more were in Chinese characters, which were thought of as being more formal than Hangeul. The English appearing on storefront windows was usually not intended to be read, but merely there to indicate that the wares inside were quality products (suggesting that they were foreign-made).

Similar to signboards, the newspapers and magazines of four decades past carried very little in English other than an occasional initialism or acronym of a proper name such as “UN” or “CIA.” Because of the abundance of Chinese characters used in 1970s’ newspapers, the college student of today would not be able to read them. English loanwords, too, were then a meager portion of the Korean vocabulary, in stark contrast to the inundation we see and hear today, over 20% by some counts.

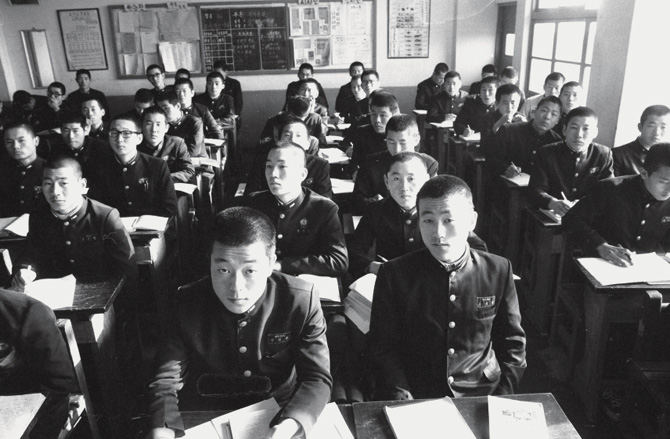

The English Classroom

The comforts and conveniences of today’s classrooms are taken for granted. The air-conditioning, central heating, and even the computer are all commonplace. The coal briquette- or sawdust-fueled potbelly stove of the ’70s failed to keep out the winter cold just as the electric fan failed at bringing the classroom down to room temperature. Classrooms were larger then, holding 60–70 high school students, compared to the 30–40 of today. The single fan or heater per classroom was no match for the extremes in temperature. Language learning materials are readily available for use in today’s classroom – games, activity sheets, songs, storybooks, readers, PowerPoint presentation capabilities, and an internet connection that opens up the world of resources to the classroom. The classroom of the early ’70s, however, was pretty much barebones, containing little more than the students’ textbooks and activity books, and if lucky, a cassette tape recorder with dialogue tapes to listen to and repeat after. Study conditions were much less comfortable and study materials and equipment were much less available.

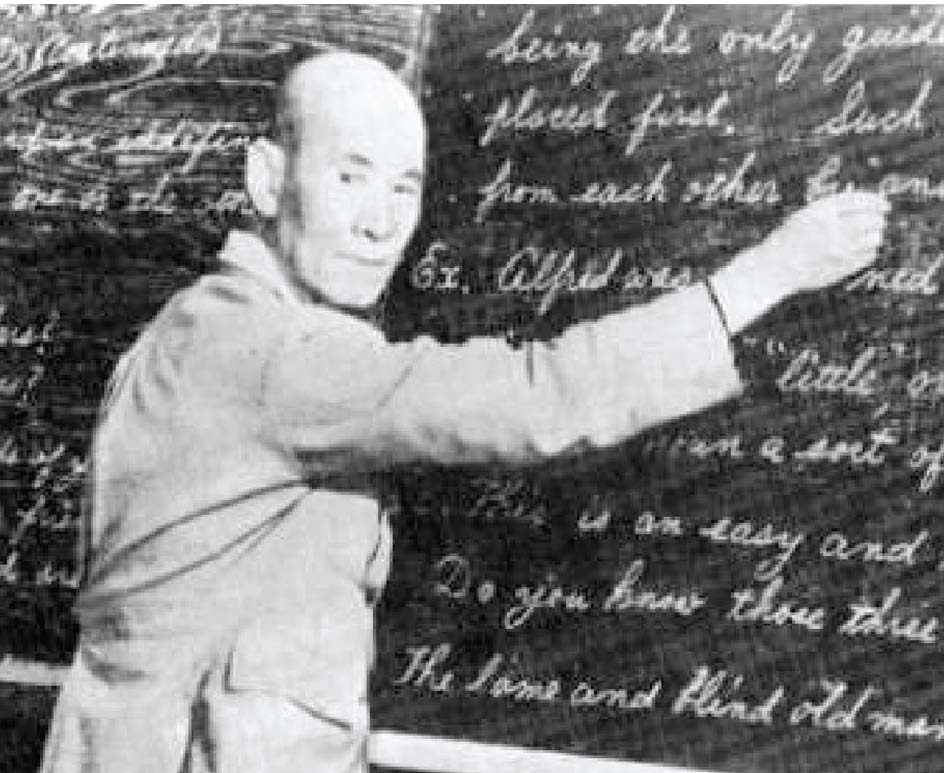

The English Teacher

The public school English teacher in Korea today is quite lucky in that there are a wide variety of in-service training programs available, both during vacation time and during the school term. Transportation and lodging expenses are provided, as are those for trips abroad for training. The school teacher is more traveled and has an international awareness. They have satisfactory communicative English skills and are versed in a variety of teaching methodologies. However, they still favor outdated, inefficient methods that may be helpful in raising student scores on standardized examinations in their test-driven world but do very little to raise their level of English skills. The English teacher of the ’70s had very little contact with English in use and only limited communicative skills. Their English pronunciation, still bearing a strong influence of the Japanese colonial period, was far from native-like. “This is a book” sounded more like “Disu iju booku.” Teaching methods relied heavily on translation with grammar and vocabulary explanation. However, the English teacher was motivated, and was recognized as the brightest and most able of teachers, as English was considered the most difficult of subjects.

The English Student

The secondary school student of the ’70s was much like the student of today in that they were both overworked and sleep-deprived due to study for school examinations and ultimately the college entrance examination, on which English, Korean, and mathematics were tested. Today’s student began English in the third year of elementary school, but likely studied at a language school or kindergarten at an earlier age. The student of the ’70s began English study in middle school. Language school English study is now common throughout the primary and secondary school years; study abroad is becoming more and more common. But in the ’70s, the English hagwon was a rarity and study abroad an impossibility. The importance of English for testing purposes has continued to provide external motivation for the English student, but it is only the more recent learner who more clearly sees how English ability can impact their future.

The NEST

The native English-speaking teacher (NEST) of the 1970s was quite a different person than the NEST of today and was found in far fewer numbers. Back then, there were a scattered few native-speaker missionaries teaching at Christian schools, but the common NEST was a U.S. Peace Corps volunteer teaching at the middle school or university level for a two-year period of service. The Peace Corps NEST was typically a recent college graduate with no TEFL training other than the basics received in Peace Corps training. Today, NESTs of various nationalities are found at every level of public and private English education, and qualifications required for employment are constantly rising with the increasing availability of distance TESOL certificate and degree programs.

A lot has changed on the English education scene between the time of President Park Chung-hee and that of his daughter President Park Geun-hye, and I expect the changes to continue at an accelerating pace in the future.