Funds of Knowledge for the Classroom

Interview with Maria Lisak.

It is obvious that knowledge is related to education and teaching EFL, but it is not so obvious what “funds of knowledge” is. Although the concept has been around for nearly three decades, the average classroom EFL instructor and others in the field of EFL education may not be familiar with the term “funds of knowledge” or the concept it refers to. To broaden our insight into funds of knowledge and its application to classroom teaching, the Gwangju News arranged an interview with longtime Gwangju resident and university professor Maria Lisak, who is researching the concept in relation to her ongoing doctorate studies. What follows is that interview. — Ed.

Gwangju News (GN): Thank you, Maria, for consenting to do this interview for the Gwangju News. To begin with, could you give us a brief overview of what “funds of knowledge” refers to?

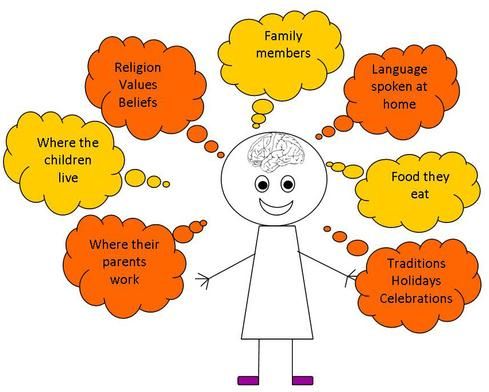

Maria Lisak: Funds of knowledge is a theoretical practice in education to understand knowledge as constructed from the socio-cultural experiences we live. While we organize knowledge by things like job or skills, it often is very hierarchical and tends to respect some knowledge more than others. A good example might be to think about a stay-at-home mom. As these are unpaid positions and are demanded of women as part of their historically biological role, there are so many “funds of knowledge” required to be a stay-at-home mom. Childrearing, homesteading, community building . . . when we think of the knowledge required to parent and care-take, the list of jobs and duties really add up. Additionally, we can think of other contextual elements such as “on-demand services” and “multitasking” as special skills that require different cognition practices in order to read the contextual cues for immediacy and kind of response. These types of knowledge are often not explicitly stated but implicitly “intuited,” yet really it comes from the repetition of experience within finely nuanced contextual shifts.

GN: Knowledge gained from lived experiences is funds of knowledge. This next question may seem like a frivolous one, but I am wondering why terms related to education employ money-related terminology. In addition to “funds of knowledge,” I am thinking of “educational capital” and “banking model.”

Maria: I had to go back and re-read my core source, González, Moll, and Amanti (Eds.) Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities, and Classrooms. The originating theoreticization was influenced by a study on rotating credit associations in central Mexico and the southwestern United States. Social justice education practices often have to start within the dominant discourse. For 21st century education, the language of capitalism and neoliberalism as globally organizing economic frames for nearly all forms of knowledge creation and perpetuation is co-opted to serve the liberating objective of social justice education by being within and against the dominant power system. This is a way to take money-related terminology and re-center its power to liberate knowledge construction from its hierarchical systemic and structural imbalances. Janks (2000) talks about being within and against the system simultaneously; the unconscious adaptation of funds as a conceptualization may come from the implicit system imbalances that the teachers and researchers (Gonzales, et al.) were coping with in the southwestern United States where the school system is more to train learners to be good workers instead of scholars. I like to think of it as people using language instead of language using people.

GN: “People using language” – that applies to the language teacher, the second language learner, and actually anyone who speaks a language. How did you get interested in the area of funds of knowledge? Did your doctorate studies pique your interest, or did your interest in funds of knowledge lead you to pursue the area further in your doctorate studies?

Maria: I ran across this conceptualization in my doctoral studies and felt that it really addressed the interests I had at the time in older adults’ resistance to digital technology. Adult education theory treats learners as fully formed human beings with a myriad of experiences and knowledge. While reading the literature, I came to realize that we need to engage with all learners, no matter how small, to assist them in realizing that they have knowledge and experience, and that they are busy making meaning simply by being active agents expressing their identity within some sort of existing power structure.

GN: So, how can we “engage with all learners”? Specifically, how can the concept of funds of knowledge best fit into content-based instruction, which I know that you do a lot of, and into EFL instruction?

Maria: I teach administration welfare, and my students often come to my class thinking they are inexperienced in these areas. Yet my students are already experts in both welfare and administration; they have lived within these systems their whole lives. Oftentimes in an ESP or CLIL course, teachers think they need to teach the textbook, often because they do not consider themselves experts in that particular area. What is a better approach is to crowdsource knowledge – from the teacher, the students, the textbook, and the internet. This repositioning of knowledge as something to be constructed, when double-checked, sets up transferable skills for any content area. Critical thinking, content validation, a survey of current issues, and student-led inquiry projects all allow for hitting the different levels within Bloom’s taxonomy of learning.

GN: Could you give us some specific examples of classroom activities, lessons, or projects that are based on the funds of knowledge concept?

Maria: I always get an interest inventory from my students about their personal interests as well as their academic interests. I think it is also important for them to start imagining themselves in their future job, so I ask them what their dream job is. This then allows me to choose and create materials for my learners that are inherently interesting, while also getting them to start seeing their role in our discipline. Other lessons include the students making resumes for themselves at different times in their life: now, in five years, and when they retire. A popular lesson is also making a book jacket based on a picture. I ask the students to interpret the picture, making a title, author bio, and abstract to go on the inside cover. Additionally, they take other viewpoints such as reviews and endorsements to add to the back cover. This interpretive exercise generates some rich and sophisticated storytelling, especially around social issues that are taboo or problematic to discuss in class. Keeping a portfolio of learner-made materials – Padlet is great for this – learners can then add work there, give feedback to others, and finally have a chance to reflect back on these artifacts to see how or if they have changed or grown.

GN: You teach at the university level. How feasible is it to apply the funds of knowledge concept at the secondary school or primary school level?

Maria: My understanding is that the funds of knowledge concept was originally developed for young learners. Hispanic families living in the southwestern portion of the US were interviewed by teachers.

Korea already does a lot of info gathering about learners and their families. But part of the problem that can be encountered is that family knowledge may be considered more as “dark” funds of knowledge (the movie Parasite is a good example of this complexity) because Korea is so status conscious. When initial questions in social situations about affiliation (military service, school, home location) are combined with detailed knowledge of family background, a toxic cocktail of classism can emerge. Korean education is very idealistic and aspirational, focusing on transformation from deficit stances. It does not necessarily see some life experience as relevant or respectable to anchor education goals. While Korea does a lot to “even the field” for lower socio-economic families, there are shocking holes in the welfare system to support those who drop out of school. For instance, multicultural families have high dropout rates, being in the double digits for elementary school-aged children. Until Korea widens its value of different kinds of knowledge – traditional and untraditional – we will continue to see socio-economic henpecking in the soil-spoon/gold-spoon system.

GN: Looking into your crystal ball, what do you see as the prospects for Korea “widening its value of different kinds of knowledge,” especially as it relates to education?

Maria: South Korea is still pretty conservative, and as long as the government leaders make policy decisions that do not address the diversity around gender, parenting, and social stigmas, things will not change much. However, the younger generations are expressing more open-mindedness about gender issues. A big win for parenting would be for single-parent families to receive a monthly income equivalent to the amount that an orphanage provides for taking care of a child. While education, especially life-long education, is celebrated in Korea, there is still a stranglehold on qualifying for job positions in the form of personal connection or qualifications such as certifications or licenses. Until seeing the funds of knowledge of these marginalized individuals and communities as valuable and enriching to society, LGBTQ+ people, single parents, and school dropouts will continue to spend their energy on safety issues instead of mainstream society learning from them and their resilience, giving the world a more holistic way to approach society’s problems, such as climate change and the low birthrate problem of South Korea.

GN: Social change is often slow here, but on the bright side, change that is gradual is often change that sticks, rather than reverting back to its former self. Thank you, Maria. I now feel a lot better informed about funds of knowledge and think our readers will, too.

Interviewed by David Shaffer, Gwangju News’ editor-in-chief.

References

González, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2006). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms. Routledge.

Janks, H. (2000). Domination, access, diversity, and design: A synthesis for critical literacy education. Educational Review, 52(2), 175–186.

Zipin, L. (2009). Dark funds of knowledge, deep funds of pedagogy: Exploring boundaries between lifeworlds and schools. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 30(3), 317–331.

The Interviewee

Maria Lisak teaches administration and welfare at Chosun University in Gwangju. She is a lifetime member of KOTESOL, and she is currently working on her EdD from Indiana University in literacy, culture, and language education.