Teaching English Back in the Day: A Korean Retrospect

By David Shaffer

With the sweltering heat and humidity of summer and the ubiquitous downpours of the rainy season, one is placed in a perfect position to ponder the past, to reminisce about bygone days.

I was recently is such a state of mind, allowing my thoughts to travel back into a mind warp to my early days in Korea and focus on how English teaching in this part of the peninsula has changed in the intervening half century.

Many expat teachers in Korea today got their start in English teaching at one of the many private English institutes that populate the streets of every population center in the nation. I did not begin my days in Korea working at a language institute (aka hagwon) – nor did any expat in Korea at the time. It was against the law. “English fever” and “English hell” are not such recent phenomena. During the Park Chung Hee administration, only a very few hagwon were granted business licenses, and those that were so lucky were limited to teaching content directly related to standardized exams such as the college entrance examination, and hiring non-Koreans to teach English was also against the law. This tight restriction on English hagwon, and hagwon in general, served to keep the fever under control, to keep parents from spending tens of thousands of won monthly on after-school classes, and to center the importance of English education on the public school system.

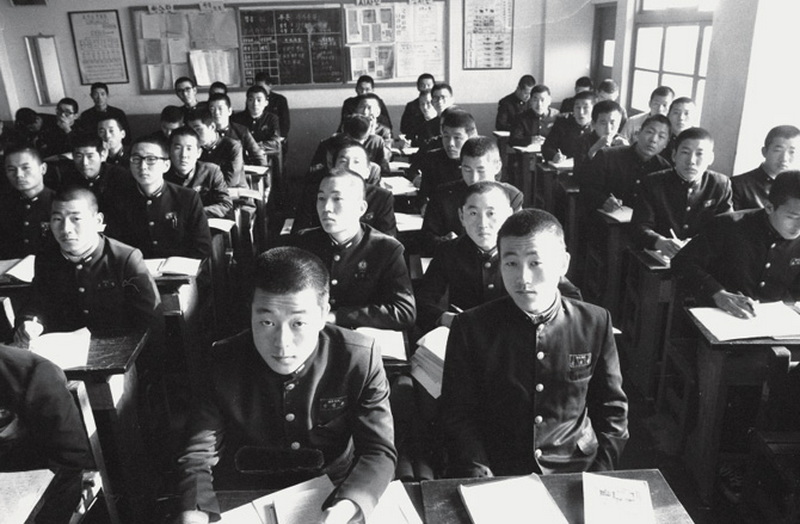

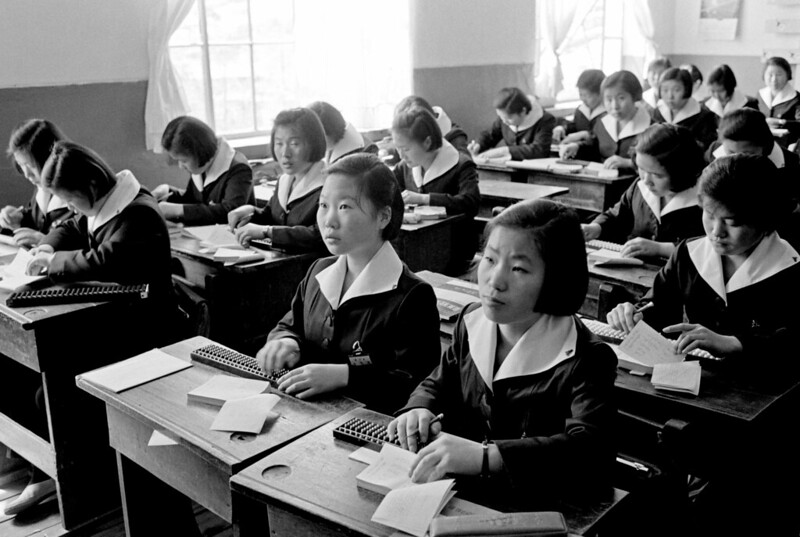

In the early 1970s, free and mandatory education was provided only through the sixth grade of elementary school across the nation. The reason being that the nation could not generate enough revenue to both develop industry and strengthen education – and industry won out. There were middle schools and some high schools located in the more populated centers of the country that were technically privately owned but requiring state accreditation, and this meant that they were tightly controlled by government regulations. Being private, these schools were allowed to charge tuition fees, but with the economy in the state that it was in at the time, families who could afford to send their children on to middle school, much less to high school, were limited. Some families had to decide with their limited incomes which of their children to send to middle school, and with Korea being a much more patriarchal society than it is today, sons, and the first son in particular, won out. In the countryside, the opportunities were even fewer: Tuition was often out of the question, and there wasn’t even a middle school in the area to go to. Moving to the city was also not a viable option for most. As an aside, it wasn’t uncommon for a university professor to have a wife with no more than an elementary school education.

With so many minimally educated children across the country, and with the government promoting industrialization and agriculture mechanization, the need for vocational education became apparent. Support was obtained from the ILO (UN International Labor Organization) for the establishment of six rural vocational centers nationwide, and a commitment of one instructor per center was provided by the U.S. Peace Corps. That is how I made my entrance into Korea – as a member of the first vocational education Peace Corps group to Korea. At Gwangju’s “Chollanamdo” Agricultural-Industrial Vocational Training Center, where I was assigned, the six-month agricultural mechanics courses accommodated about 25–30 students from rural Jeollanam-do, about half of whom had only an elementary school education and the remainder with some degree of middle school schooling. As such, English medium instruction was not an option for me. Fortunately, however, the course was set up so that most of the time was spent in the workshop. At the time, the Korean gyeongun-gi (경운기, rotary tiller) was making its debut on the market, and its operation and repair was a big part of the curriculum, along with metalworking, welding, and lathework.

It was only in the late 1990s that English education was introduced into the Korean elementary school curriculum. This meant that for the many youths with only an elementary school education in the 1970s, they had received no exposure to English at school, and most likely would not afterwards. Then, English study only began in the first year of middle school and continued throughout the three years of high school. New middle school students entered their schools as true beginners. You may wonder why these students’ parents didn’t seek outside sources of English learning in advance to prepare their children for in-school English study as is so common today. Two main reasons: money and availability. Family size was larger back then (my wife was one of eight children). But more importantly, English learning options simply were not available.

As mentioned earlier, English hagwon were very few, and the ones that did exist were geared to entrance exam preparation. There were no English study programs on TV – no EBS station – and there was no English language programming – such as Friends. In fact, there was very little TV: There were only two television stations (KBS and MBC), and broadcasting time was limited to 5 p.m. to midnight daily. Even this evening TV programming was watched by very few, as the average family could not afford a luxury item such as a portable TV with a 12-inch screen. What about radios? No English programming there either. Voice of America and BBC did broadcast internationally in English on short-wave radio, but the catch was that short-wave radios were banned in Korea: They could be used as a means of communication by spies for the North. What about English study books in the bookstores? None, or nearly none. What about tape recorders and English study tapes? Like televisions, a tape recorder was a highly expensive piece of equipment, and English study tapes were not yet a thing. But what about English-speaking expats to do private tutoring? They were not a thing yet either back in the early 1970s.

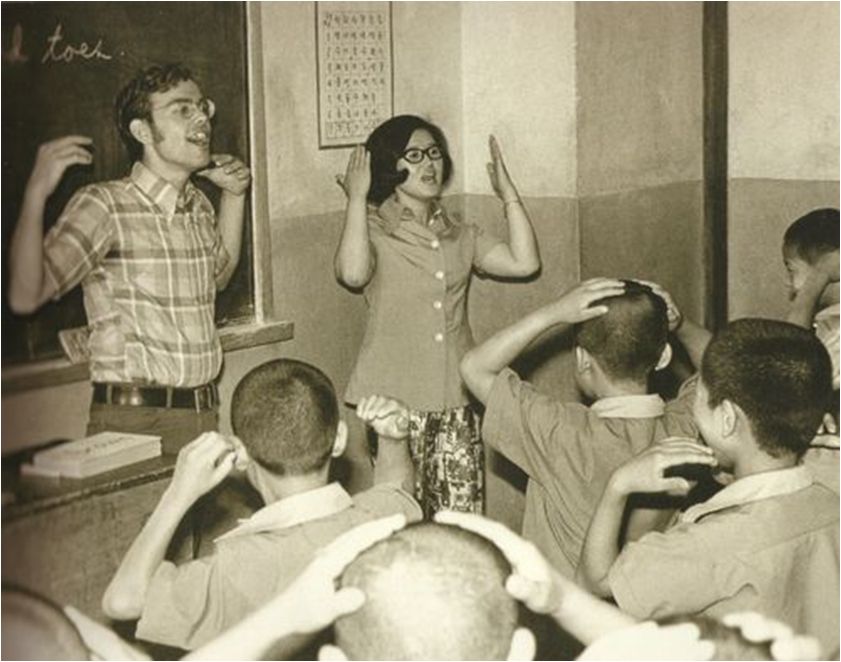

What Korea did have, though, in addition to their own public school English teachers, were U.S. Peace Corps-sponsored English teachers. From the late 1960s to 1980, young Americans were posted as English instructors at many of Korea’s middle schools, as well as in university positions. High schools, because of their almost singular focus on university entrance exam prep, were not considered to be an optimal placement for Peace Corps instructors, as English instruction there focused on the memorization of grammar rules and vocabulary items. Korean English teachers were better schooled in such pre-contemporary teaching techniques.

Before being placed in middle schools, Peace Corps instructors went through training in English language teaching and Korean language learning. Before they first entered their Korean classrooms, they brought with them many years of experience as students in interactive classrooms – something still quite foreign to Korean students and teachers at the time. They also brought with them modern language teaching techniques, such as pattern practice, learning English through song and games, and the most basic of all: speaking English in class instead of merely listening to explanations about it! The Peace Corps English teaching program had a major impact on modernizing English teaching in Korea. Korea’s EPIK teacher recruitment program that materialized in the mid-1990s was patterned in many ways on the Peace Corps English teaching program, but much before that, the Peace Corps program was making an impact.

A major impact that had its origins in this “City of Light” started at Chungjang Middle School in Sansu-dong. There, a Peace Corps teacher and her co-teacher came up with the idea of a short, tape-recorded listening test of five questions. It so happened that the middle school was designated as a research school, and the co-teacher was a “research teacher” who reported the results of the school-wide listening test to the provincial office of education. The provincial office liked what they heard and decided on taking the simultaneously conducted listening test province-wide. I was part of the team forming the questions and recording them for the first few series of these province-wide listening tests. After the technical kinks were worked out, the English listening test format was established nationwide and developed in what it is today as part of the university entrance examination.

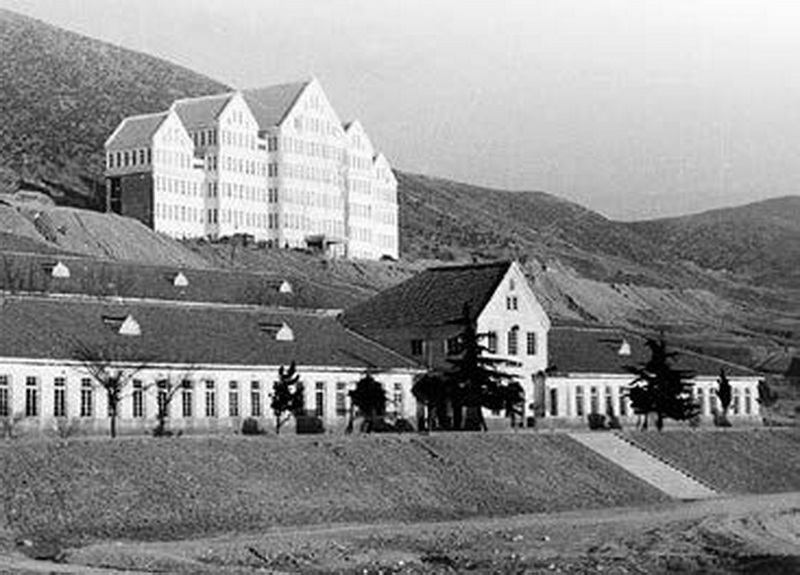

By the time Chungjang Middle School was experimenting with listening tests, I had completed four years with Peace Corps and had taken up a teaching position at Chosun University, not too far down the street from Chungjang Middle School. As Chosun University was pretty much a typical example of a university in Korea in 1976, I will describe university facilities and materials of the mid-1970s by describing my teaching situation during my first years at the university.

At the time, there were only five university-related buildings on a sprawling Chosun University campus that now houses 60-some structures, and most of those first five were much smaller than they are today. The Foreign Languages Department, which I was a part of, was in the Main Building, and all the 15 or so professors in the department were in one large room with desks in a circle facing each other, with the department head sitting at a large desk at the head of the circle, much like at primary and secondary schools. Buildings did not have central heating or air conditioning at the time. In the coldest of winter, coal briquette space heaters were installed in offices, and in the hottest of summer, one electric fan per large office. Regardless, the temperature often remained too extreme to be able to do any real work at these times, but office hours, even though it was student vacation time, remained 9 to 6 on weekdays and until 1 p.m. on Saturdays.

Classrooms did not have the luxury of electric fans or coal briquette heaters. Desks and chairs were made of course wood, with the green paint on the plywood desktops making them smoother and less splinter prone. On the front wall was a chalkboard, also made of plywood but with coatings of paint to make it much smoother than the desktops and to make the chalk much more easily erasable. Also in the front of the room was a wood-and-plywood lectern with little finish and often wobbly on its floor of gray concrete.

My language skills classes of 15–20 students were smaller than average university class size, and much smaller than the 70–80 students that these same students had been used to in high school. Because of this small class size, my classes were assigned to the smallest classrooms, which just happened to be located directly under the gabled roofs that the main building is noted for. I intentionally said “roof” rather than “ceiling,” because the corrugated roofing of these gabled roofs were the classroom ceilings, from which a single incandescent light bulb hung. In the back of the room, there was an open-air gap between the eave of the roof and the wall under it for ventilation and giving the room its natural light. So, these rooms were cold in wintry weather, hot in summery weather, windy in stormy weather, and noisy and dingy in rainy weather. We all know that none of these conditions are conducive to effective learning.

I seem to remember that the classrooms did have an electrical outlet, though there were no tape recorders or electric fans available to plug into them. However, the university was installing a language laboratory where all freshman students would take their mandatory Laboratory English courses in the new-to-Korea audiolingual format. When I was taken to the downtown bookstore to choose a coursebook, there was a total of two English language coursebooks to choose from. Both were based on listen-and-repeat dialogues that were popular teaching methodology at the time. Little else was available as teaching or learning materials – other than the requisite six-centimeter-thick English–Korean dictionary that each of my students carried as a badge of studenthood. With only a fourth of youths going on to university, a tertiary education was considered a privilege rather than the societal requirement it has become today.

Though English education in Korea is still overly reliant on grammar-rule learning, vocabulary-word memorization, and standardized-test preparation, the nation has, nevertheless, made great strides in English language learning and teaching. From dusty blackboards to interactive whiteboards. From the lone classroom teacher to the chatbot and English-teaching robot. From the occasional tape recorder to the wired classroom with computer console and everything the internet has to offer. It’s difficult to fully realize how substantive the changes in English education have been in the last half century in Korea.

The Author

David Shaffer has been involved in TEFL and teacher training in Gwangju for many years. As vice-president of the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter of KOTESOL, he invites you to participate in the chapter’s teacher development workshops and events (in person and online) and in KOTESOL activities in general. He is a past president of KOTESOL and is currently the editor-in-chief of the Gwangju News.

Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL

Upcoming Events

Check the Chapter’s webpages and Facebook group periodically for updates on chapter events and other online and in-person KOTESOL activities.

For full event details:

- Website: http://koreatesol.org/gwangju

- Facebook: Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL