And on the Seventh Day, the Economy Rested

By Isaiah Winters

The City of Light seems to have more evicted neighborhoods, urban wastelands, and towers of concrete than ever before. It’s gotten to the point where spindly construction cranes, now just another familiar part of the cityscape, are rivaling the ubiquitous red crucifixes in number and visibility. The new god muscling His way through our urban environment is, of course, “the Economy” – so, same as the old god, really. From the rubble of old neighborhoods that struggled to pay their tithes, He resurrects new taxes, consumption, and debt. This redevelopment process is hard, relentless work that requires a break now and then – every Sunday, in fact.

Sunday is when I’m busiest in urban redevelopment zones, as that’s when the wrecking crews all go home and the derelicts they destroy are left wide open. The same sites that are normally better surveilled and buzzing with activity the other six days a week suddenly become porous and poorly guarded, giving observers like me the chance to slip in and spot anything evincing neglect or nostalgia. The aim is to digitize these finds through writing and photography so that demolition processes don’t remain so obscure and so that Gwangju’s past attains a sliver of immortality online. This is the voodoo I work on the demolition economy’s weekly day of rest.

On a few recent sabbaths, I took some friends from out of town to a pair of redevelopment sites in the city. Both sites were in quite an advanced state of demolition with little left to see; however, these often yield the starkest contrast shots. There’s something about a lone building bearing the scars of some awful process that hits home hardest. For instance, today the Gerhardt Mill stands as a battered testament to the Battle of Stalingrad, while the Genbaku Dome in Hiroshima reminds us of the trauma of nuclear war. These two buildings were sacrifices made to another destructive god known as War. Similarly, our sabbath tours through Gwangju centered on casualties of the Economy.

One such casualty was in Unam-dong. There, Unam Jugong Apartment Complex 3 offered us a half-demolished apartment building that stood surreally alone where over 60 similar buildings used to be. Featured in this year’s March edition of Lost in Gwangju, said complex was unique in that each five-story housing unit had a gabled rooftop covered in hanok-style tiles. This plus its dense grid of cherry tree-lined roads seemed like a decent compromise between local and imported aesthetics as well as between high-density urban housing and lush green spaces. Now that the neighborhood is already midway through its transformation, it’s ripe for some of the best contrast photography in the city. Looking back at the photos taken that sabbath, the lone apartment we shot reminds me of some poor, hastily half-eaten zombie victim.

A second casualty was found atop the mostly barren redevelopment heap in Gyerim-dong. Unlike the previously mentioned complex, this area has gotten the slow treatment, with some buildings still standing years after eviction. Today only a church, a motel, and an especially tenacious kindergarten are holding out against all odds. One hilltop apartment building in the area offered a particularly striking living room view of encroaching redevelopment. The reclining chair, turned away from the hubbub outside, indolently faces where the TV used to be, while outside the window, the faded turquoise kindergarten holds on for dear life. When shooting this scene, the phrase “armchair optimist” sprang to mind to describe those who always consider redevelopment a win-win despite never really seeing it for themselves.

There was a third redevelopment zone we tried to visit – the massive jutaek village in Singa-dong, featured in the October 2020 edition of Lost in Gwangju. For context, it’s long been the most tightly surveilled and best protected eviction site in the city for some odd reason. A few Fridays before our revisit, I noticed that redevelopment tarp had already enveloped the entire neighborhood and the main traffic arteries in and out had manned checkpoints where visitors had to sign in. This didn’t bode well for our upcoming visit, but surely the sabbath would ensure our deliverance, right? Wrong. It turns out that the redevelopment zealots in Singa-dong are such firm worshipers of the Economy that their demolition services run seven days a week.

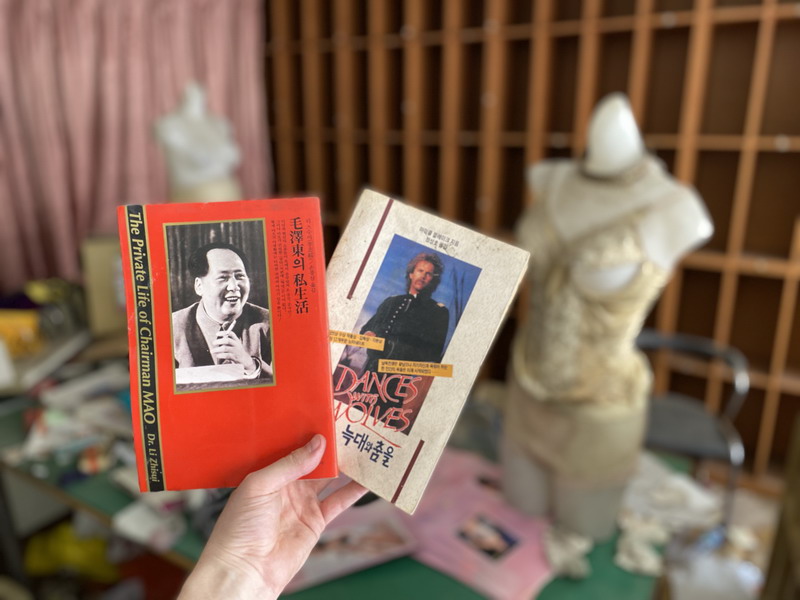

Knowing I’d never part the tarp sea in Singa-dong, I returned to Gyerim-dong once more with another friend one sabbath to see what little remained. We scoured every nook and cranny of the street-front businesses hidden behind the redevelopment tarp hoping to find something of interest. What stuck out was just how dense the neighborhood’s network of failed businesses was. A hanbok shop with its mannequins – one sporting a traditional Korean manbun or sangtu (상투) – resided under a second-story pool hall with one remaining table. Nearby, a tailor shop filled with buttons, fabrics, and a clunky overcoat press we called the “iron lady” shared a building with a soju bar still proudly sporting a “2002 World Cup Korea” signboard outside. Adjacent to these was a lingerie shop scattered with granny panties and sultry paperbacks with hunky tales like Dances with Wolves and The Private Life of Chairman Mao.

Given that these and many more mom-and-pop shops surely contributed to the Economy, isn’t it a paradox that they fell victim to redevelopment anyway? I guess the Economy works in mysterious ways.

Photographs by Isaiah Winters.

Born and raised in the shadow of an infamous Californian prison, Isaiah Winters is a pixel-stained wretch who loves w

The Author

Born and raised in the shadow of an infamous Californian prison, Isaiah Winters is a pixel-stained wretch who loves writing about Gwangju and Honam, warts and all. When he’s not working or copyediting, he’s usually driving through the countryside on the way to good beaches or mountains. You can find more of his photography on Instagram @d.p.r.kwangju.