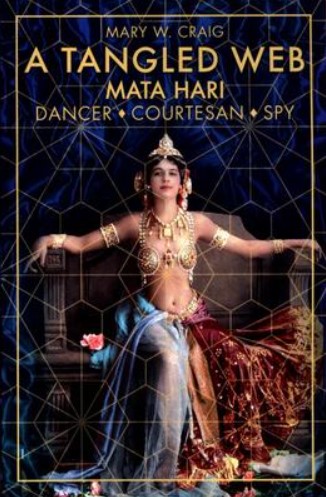

A Tangled Web: Mata Hari: Dancer, Courtesan, Spy

Mary Craig is an historian specializing in the history of central Europe from 1848 to 1933. Mata Hari was born in 1876 and executed in October 1917. The biography reads more like a text book than a novel. This is not a negative criticism but rather reflects the author’s objective approach to the many, often confusing details. The introduction serves as a summary of Mata Hari’s life, including her tragic ending. It would appear that the author presumes that Mata Hari’s notoriety is such that her execution is already known to readers.

As a young girl growing up in the Netherlands, she attended private school, but this ended with her father’s bankruptcy. After her mother’s death, M’greet as she was known, was sent to live with her godfather, who was also her uncle. She was 15 years old. She never did fit in with others. “She was dark-haired and olive-skinned, in distinct contrast to the blonde, pale-skinned idealised notion of beauty in the Netherlands.” She was also tall at 5ft 9in (175cm).

The author cannot offer a firm explanation as to why M’greet was sent to be trained for a job while other young women were being trained for marriage. This is especially confusing in that she was never offered a job at any of the various family businesses. At one point, she was training to be a kindergarten teacher. And as would be the case throughout her life, the combination of circumstances and personal choices would lead to difficult situations. M’greet, then 16, became involved in a sexual relationship with the 51-year-old headmaster. Once the scandal was discovered, she was forcibly removed from the school. “M’greet acted not with contrition but defiance. And it was that which condemned her in everyone’s eyes.”

This early event in M’greet’s life is put into historical context by the author. The female was automatically seen as the guilty party. And the fact that the woman readily admitted to the enjoyment of sex was conclusive proof that she was depraved. This carried forward, and when the question of whether or not she was a spy was before the all-male military court, her morals and perceived depravity were equated with the character of a traitor.

Her story is interesting from start to finish. She marries a military man, and shortly after the birth of her son in 1897, the young family set sail for the Dutch-controlled East Indies. For M’greet, “Colonial life was a mixture of work and boredom.” The marriage was already spiralling downward, with violence an almost daily event. She found a partial escape through dance. The author is intent upon telling M’greet’s story within the context of the time and calls out the illusion of glamor. “The social façade that hid the brutality of empire was necessary to maintain the fiction of bringing civilization to the natives.”

After a return to the Netherlands, there was marriage separation and the earning of a living by, “entertaining gentlemen callers in maisons de rendezvous.” In 1903, she moved to Paris. She pursued Oriental dance and “created an illusion that masked her inabilities as a dancer.” In 1905, she is introduced as Mata Hari. It was La Belle Epoque, and Mata Hari was a queen. There were performances in Moscow, Madrid, Monte Carlo, Vienna, and Berlin. And there were just as many lovers. There were ups and downs over the years, but by 1914, she “was starting to enjoy life again.” “This was broken in July when the politics of the Balkans broke into her world and shattered it forever.”

At this point in the book, there is a noticeable change. The confusing details start to come quickly and the author puts forth more questions and speculation than known facts. Again, this is not negative criticism, but rather illustrates the complexity of unravelling history. We do know that Mata Hari was approached by German intelligence, that she did not refuse, but rather haggled over how much she would be paid. And to the author’s mind, Mata Hari, “failed completely to see the danger.”

She began to travel all over Europe, which was not easy to do in time of war. She persisted in her attempt to get travel papers to an area of France that was a military district, supposedly to recharge her health in the natural mineral waters. Why not go to another health spa? She later claimed that it was at this time that French officials broached the subject of her working for France. This was later denied by those officials. By now, she had raised the suspicions of the British, and they had her under surveillance. Mata Hari continued to live as lavishly and flamboyantly as she always had. For the French, this was another indication that she was a spy. Her lifestyle did not project support for the French war effort. And all along she had her lovers, almost all military men.

The movement of events can become tedious for the reader. There are a lot of names to remember. Eventually, Mata Hari is arrested by the French. The author again reminds us of the male dominated world view. The investigating magistrate believed that she was guilty from the start. “Innocent women don’t get arrested.”

She was in prison for eight months. Admitting that she had been recruited by the Germans was not helpful, and then there were revealing telegrams. However, there was never evidence of what exactly she is supposed to have revealed to the Germans. The trial took two days, one for the prosecution’s case and the second day for the defence. Cross-examination was not allowed, and the threshold of proof was low. She was found guilty and sentenced to be shot.

The Reviewer

Michael Attard is a Canadian who has lived in Gwangju since 2004. Though officially retired, he still teaches a few private English classes. He enjoys reading all kinds of books and writes for fun. When the weather is nice, you may find him on a hiking trail.