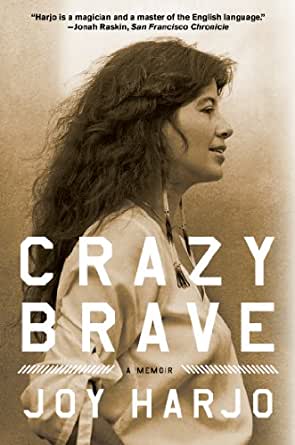

Crazy Brave: A Memoir

By Joy Harjo.

Reviewed by Kristy Dolson.

Joy Harjo, a member of the Mvskoke (Creek) Nation, is the first Native American United States poet laureate. Crazy Brave: A Memoir details her heartbreaking journey to poetry and music through hardship and oppression. Born to parents who came from two different First Nations tribes, their relationship was edged with danger, and her father left when she was still a child. In the church, she began to doubt herself and internalized a self-loathing for her female otherness. As a young woman, she was stalked and nearly raped many times – sometimes by her stepfather, who turned out to be no savior to her mother and siblings. She turned to alcohol, drugs, and art to escape the abuse. Despite growing up in a social and political order that wanted to see her fail, her courage and strength made it possible for her to survive and eventually thrive.

Harjo begins her memoir with a beautiful and inspiring epigraph and ends it with an afterword full of forgiveness, while the main narrative is separated into four parts. Representing the four cardinal points of the compass, each begins with a short description of what these directions signify. Harjo’s poetic talents are on full display. Each direction also plays an important part in Harjo’s story, as she moves around the country following her dreams and her love for both art and people. As a poet and storyteller, there are snippets of poetry and story weaved throughout, breaking up the more linear narrative of her journey from birth to the present. It moves quickly, and with a fluid grace. It is much more beautiful than a memoir about abandonment, abuse, and racial genocide has any right to be.

I am no stranger to the historical or present injustices done to North America’s First Nations peoples. But I am also painfully aware that that history has been willfully and forcibly overwritten by its European conquerors. Crazy Brave is an act of remembering a brutal personal and tribal history. It is an act of rebellion against would-be conquerors. It is a story more people need to hear. Harjo relates her story with compassion and the forgiveness of an older woman who has learned to let go of the failures and pain of her younger self. I am glad that she can forgive. But I am relieved that she does not forget. Abusers would have their victims “forgive and forget.” We should not forget. Even now, Western governments are working hard to disappear their native populations. We must not allow this to happen.

One of the most disturbing atrocities Harjo recounts is her first experience giving birth. In a joyless military hospital, she was given a form asking for permission to sterilize her after the birth. She declined. At the time, she did not give the incident much thought, but later she realized how close she had come to being another victim in the U.S. government’s blatant attack on First Nations women. Only her fluency in English saved her. Most women of her generation could not read the form and signed thinking it was just a consent form for the doctors to deliver their babies. Many women were sterilized without even this misleading formality.

After suffering years of abuse at the hands of her resentful mother-in-law and a husband who never learned to grow up, Harjo finally broke free and followed her passion for creative expression. In her memoir, she gives thanks to the Black Power Revolution of the 1960s, grateful for the awakening it spurred in Native American people across the land. The revolutionary spirit unleashed a rising tide of change in a generation that wished to bring back strength and recognition to their individual tribal nations. She joined the tide, adding her voice to the surge, and gained strength. Although it was heartbreaking to read about her adolescence and young adulthood as a disenfranchised woman with a yearning to be an artist, in the end I was uplifted by the hope and light Harjo found in poetry.

It is fitting that I was introduced to this book by my colleague Dr. Park during her June KOTESOL Reflective Practice meeting. As a person of European heritage, I must constantly reflect on my position of white privilege. Asking questions, seeking diverse viewpoints, listening to the experiences of the marginalized and donating our time, money, and voices in the ongoing struggle against injustice are practices we should all be embracing.

The Reviewer

Kristy Dolson lived in South Korea for five years before taking a year off to travel, read, and spend time with her family in Canada and Australia. She holds a Bachelor of Education and now just returned to Gwangju where she splits her time between teaching at the Jeollanamdo International Education Institute and reading as much as she can.