The Return of the Celadons: A Visit to the National Research Institute of Maritime Cultural Heritage

Written by Monk Jang Gyong

Whether one likes it or not, we live in societies that are embedded in a larger and more homogeneous system of global capitalist organizations. Perhaps it is good to know that we as humans were not always living in such a manner. For a long, long time, we were living in worlds that were not at all like the world is today.

In fact, the Industrial Revolution occurred only about 200 years ago. If we roll back a few more 200 years on an imaginary timeline, we find that authentic and almost everlasting manually produced products were shipped to and fro around the Korean Peninsula – artifacts that embody a refined combination of craftsmanship, natural elements unique to geographic locations, and a delicate proportional balance of visual characteristics, to say nothing about functionality.

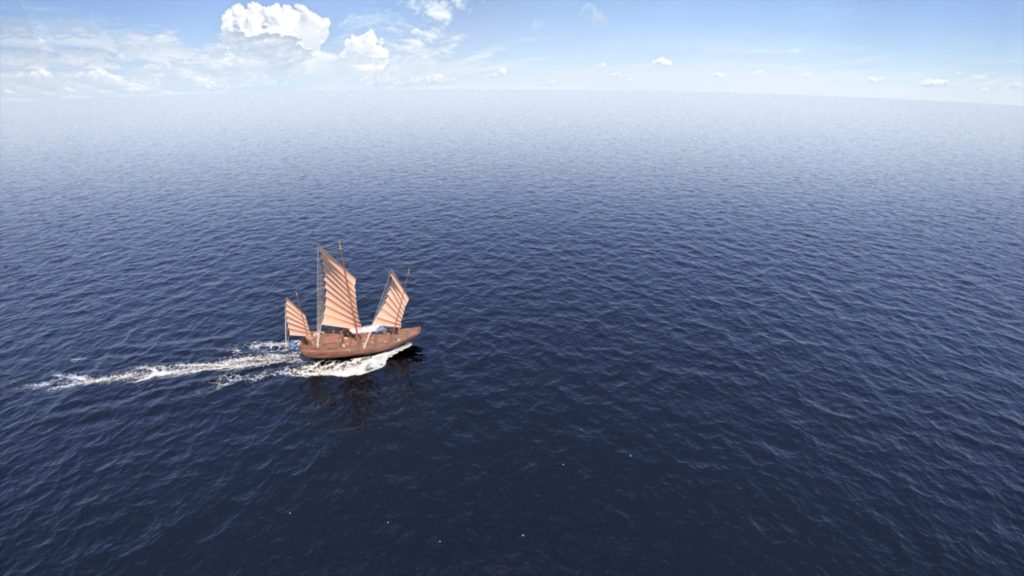

The ships that were carrying these goods on the eastern section of the so-called Maritime Silk Route were made of wood and were equipped with tightly woven canvases to harvest the power of the winds. The sailors on board most likely relied almost entirely on their natural senses for navigation: during the daytime by looking at the horizon and the position of the sun, at night by looking at the stars.

One thing is without a doubt: The relics on display in the exhibition halls of the National Research Institute of Maritime Cultural Heritage would, if placed in water, sink without fail and without exception. They were placed in water and did sink: Many of the artifacts on display were once the ceramic cargo of a Chinese trade ship of the Yuan Dynasty that sank off the coast of Jeollanam-do in what is now Shinan-gun back in the 14th century. As for the artifacts, which include many celadons, they have been preserved well over the centuries.

It is hoped that the record below of a conversation I was fortunate to have will encourage some to embark on a journey of learning about ancient maritime exchanges that took place several hundred years ago around the Korean Peninsula. The partner in my conversation was Shin Jong-kuk, section head of the Exhibition and Public Division of the above-mentioned institution, who was not only a patient and understanding companion but also a knowledgeable guide who would anticipate unasked questions and provide detailed explanations when needed.

Jang Gyong (JG): When did the National Research Institute of Maritime Cultural Heritage open its gates and what led to its establishment?

Shin Jong-kuk (Shin): The Shinan shipwreck was excavated beginning in 1976 and continued for about nine years until 1984. The porcelain relics excavated there were transferred to the National Museum of Korea in Seoul. The ship’s hull was salvaged in 1981, and since it could not be sent to the museum, it was deemed at the time that it should be preserved in the urban area near Shinan district where the Shinan shipwreck was excavated.

So we built a structure near the current museum to preserve the hull of the Shinan ship in Mokpo, which was the beginning of the museum. At first, it was built to have the hull of the Shinan ship go through preservation treatments, but during the preservation process, there were many requests to build an exhibition hall here as well, since the remains of the Shinan shipwreck came from a nearby area. So the National Maritime Museum was built here in 1994. The current official name is the National Research Institute of Maritime Cultural Heritage. Not only are relics exhibited here, but we also dive and excavate underwater cultural assets, and in the process, investigations have been carried out along with research. So in 2009, the museum changed its name to that of an institute and developed into a comprehensive organization that has research, investigative, and exhibition functions.

JG: For a simple visitor, this may only be a museum with fascinating maritime history on display, but I am finding that there is a wide range of activities that the people who work here are involved with. What are some of the various activities that the Institute carries out?

Shin: First of all, our research center displays underwater relics and contents related to centuries-old trade overseas, including the Shinan shipwreck relics. Secondly, we are the only institution in our country that can excavate and investigate underwater cultural assets. So we do research on them, and since sunken ships come with artifacts, we study not only traditional ships but also island cultures related to various marine cultures.

JG: The first exhibition room hosts shipwrecks from the Goryeo period. If I have understood correctly, there is something special about the markings on the bottom of some of the white porcelains. Can you please explain?

Shin: These ceramics were not made in Korea but in China. They were made mainly in Fujian Sheng and Zhejiang in China, and the pottery from there often has various letters written on them. These markings indicate the maker of the pottery or a shipping company.

JG: According to the explanation in one exhibition room, some shipwrecks were discovered through fishermen finding artifacts in their nets. Does this still happen sometimes?

Shin: Most of Korea’s underwater sites are found when reported by fishermen or people scuba diving as a hobby, and we go to the site and check if there are any artifacts. It was like this for the Shinan shipwreck, and the Wando shipwreck. There are a lot of ships that are found by fishermen and residents reporting them. So far, 14 ships have been excavated, and most of them have been found this way.

JG: Amongst the relics of the Goryeo era, there are some jars that look a bit like kimchi pots, but strangely they have four handles. What could be the reason for having four handles?

Shin: This is from the time of the Goryeo Dynasty, but not from Goryeo. This pottery is from Yuan. The four “handles” are not actually handles; they are rings that are used to tie down a cover, something like a wooden board or a lid, to prevent the contents from being spilled out. When you tie it with a string, you need not two but four rings to tie it securely.

JG: In the same exhibition room, there is a group of celadons that seem to be unusually rich in decorations, especially on the inner sides of the vessels. They even seem more curved than other bowls from the same era. Why do they look so different, if I may ask?

Shin: The inlaying technique had been invented uniquely in Korea from the mid to late 12th century. Koreans learned how to make pottery in China and further developed it in Korea. The inlaying technique was first introduced to Korea in the late 12th century and developed in earnest later. This pottery was found in a site called Doripo, Muan (도리포, 무안), which was excavated in 1995 and 1996. This artifact was made in the late 14th century. During this period, celadon vessels were larger than those of the previous period and had an inlaid pattern. Just as celadon pottery is characterized by the specific time during the Goryeo Dynasty in which it was made, these also represent the characteristics of the period in which they were made. The bowls are larger in size and the curvature has changed. Most of the other artifacts from other regions are similar. These items were not made in China.

JG: Nowadays, trade and international relations seem to be much related. By excavating and researching maritime artifacts, can experts determine what international relations were like in different eras?

Shin: There are some things you can find out from the relics. From the Unified Silla Period to the Goryeo Dynasty, overseas exchanges were active, but from the Joseon Dynasty, a policy against maritime trade prohibited the people from going out and trading by sea (해금정책; 海禁政策). Maybe there was a problem with pirates, and the Joseon Dynasty limited exchanges by sea, following the policies of the Ming Dynasty of China. The exchange between the Ming and Joseon Dynasties involved envoys and diplomats traveling overland, so relics from the Joseon Dynasty do not appear much in the sea. Written records show that merchants of the Song Dynasty went back and forth from Song to Goryeo several times during the Goryeo Dynasty, so if you study discovered artifacts together with the written records, you will be able to better understand the international trade relationships of that time.

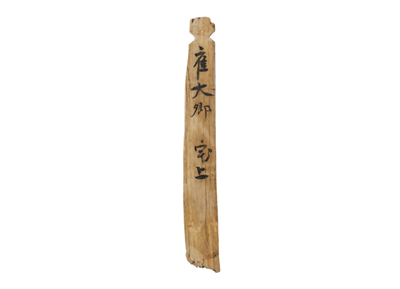

JG: What was the function of those wooden items that look a bit like large ice cream sticks that seem to be on display in every exhibition room?

Shin: These days, if you send a package by parcel service, a waybill is made. It tells what is in the package and how it should be delivered. These wooden documents recorded basic information about the cargo: information about the shipment site, the region, and the contents of the cargo. For example, if the contents of the cargo were grain, the information would be expressed in terms of bags of wheat or seeds, the receiver of the cargo, and the amount of grain.

These wooden documents are important because there are quite a few people in other written records, such as Goryeosa (고려사, History of the Goryeo Dynasty), who are named in these documents as recipients of the cargo. These are important documents that show where the cargo originated, where it was going, and roughly when the vessel was shipwrecked. This is the most important piece of data that has recently come out of the ship.

JG: I have read in the second exhibition hall that most of the passengers of the sunken ship were monks who were to return to Japan from China. How is it possible to know the professions of the passengers?

Shin: We do not know exactly. It is only an assumption, but during the Tang Dynasty and the Yuan Dynasty, many people went to China from Japan or Korea to study, especially monks. According to the annals of the Goryeosa, the sinking of the Shinan ship in 1323 was in the Yeong-gwang (영광) district, and there are records of the repatriation of 220 Japanese who drifted into the area of today’s Shinan district. There is a record in Japan of a Japanese monk named Daejisunsa (大智禪師, 1290–1366) who drifted into Goryeo in 1324 and was repatriated to Japan in 1325. It was assumed that this is a record related to the sinking of the Shinan ship. Based on these records, we think that monks were on board, and since much of the Shinan ship’s cargo is from a temple in Kyoto, Japan, named Dongbok-sa (東福寺,Tofukuji), it is reasonable to assume that monks were on board, but it is not certain.

JG: What are the ongoing exploration plans of the Maritime Research Institute?

Shin: Currently, we are excavating in the Jeju Island area and the Taean (태안) area. These are our main areas of focus.

JG: Thank you, Mr. Shin, for the interesting information that you have provided in this interview.

Interview translated by Yoo Yeon-woo

Photographs courtesy of National Reserach Institute of Maritime Cultural Heritage and Mokpo MBC

The Author

Monk Jang Gyong was born and raised in Budapest, Hungary. He learned about Korean Buddhism through the activities of the late Zen Master Sung Sahn. He came to Korea and became a monk in Seoul at Hwagye Temple in 2008 and has since been living and practicing as a Buddhist monk in temples throughout Korea. As for Gwangju, he practiced and lived at Gwaneum Temple between 2014 and 2017, and studied Korean language at Chonnam National University. Currently he resides at Buddha Zen Center, Busan.