You, The One, Standing in the Prosperous Land

Written by Robert Grotjohn

Photographs courtesy of Gwangju Museum of Art and Robert Grotjohn

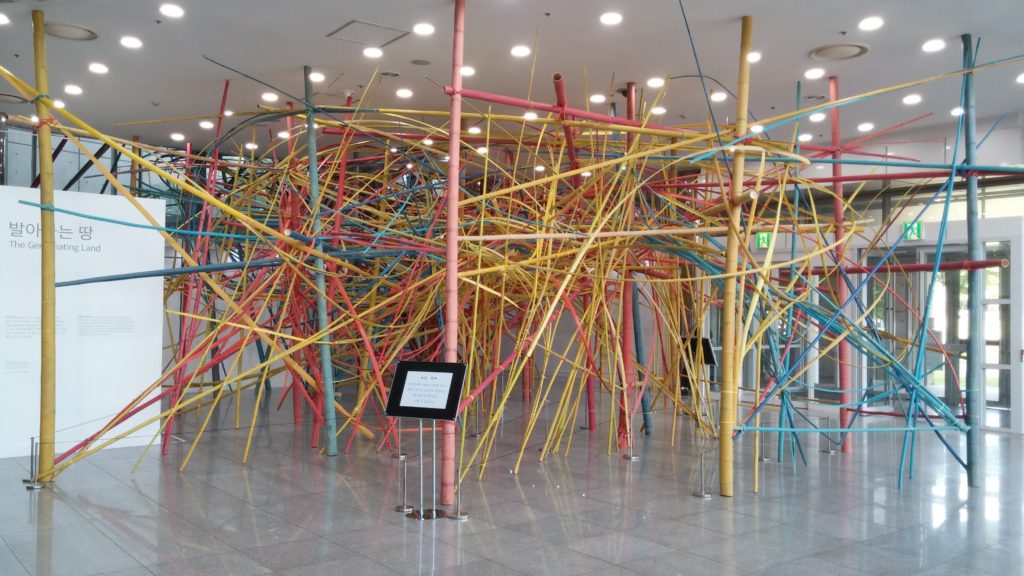

During the last week of June, the foyer of the Gwangju Museum of Art (광주시립미술관) in Jungoe Park was filled with several hundred pieces of bamboo of various lengths painted different shades of the three primary colors: red, yellow, and blue.

A few of the longer pieces were tied to the bare metal framing of the museum walls in the back corner of the exhibition space. Over the next two weeks, the rest of the bamboo was gradually added to the installation created by Ma Jong-il with the help of his old friend Kim Jong-yop and several assistants. I talked with him several times during that process.

Ma grew up in Jangheung, Jeollanam-do, and relocated to New York 22 years ago. He was back to help commemorate the establishment of Jeolla-do a thousand years ago by creating part of the exhibition titled “Millennial Heaven, Millennial Earth” (천년의하늘, 천년의땅).

Ma’s installation, one of four, responds to the theme of “The Germinating Land” (발아하는 땅) and is titled “You, The One, Standing in The Prosperous Land.” He did not explain the title, suggesting, rather, that viewers should come up with their own interpretations.

In discussing the piece, he asked me to imagine the Brooklyn Bridge and the way its cables and towers carry the stress and tensions of the structure to keep it stable. He suggested that I think also of the exposed metal framework of the museum itself, or of the way societies might accommodate the stress of different people and groups.

The structural support on which those ideas hang comes not primarily from the structures in the open area visible from the entrance but from the stairway and exposed metal framework behind the intertwined, twisting mass of bamboo that is the finished work. Much of the stairway is blocked from view by a ceiling, and the viewer must walk around that section of ceiling and a low wall to see how the piece climbs up the stairway.

The finished installation has four key parts. The supports tied to the stairway are one. The other three spread out on the floor. One area is predominantly yellow, one predominantly blue, and one predominantly red, although all the colors mingle in each area. Split bamboo bent into curves and circles creates flows within and between each section. Several pathways run through the piece so that viewers can enter directly into and stand within the work itself, seeing it from multiple angles, some of which turn the three basic colors rainbow-like in their proximities.

The egalitarian openness of interpretation from various angles suggests more layered ways of seeing the installation as a part of millennial Jeolla-do. That openness and the bamboo itself echo some of Ma’s own story.

In the U.S., he often works with wood, but bamboo was more useful for expressing his ideas in the process of creating the piece here. It is a familiar material that ties into his Korean roots. He grew up with it, and it means a lot to Korean culture. It is a beloved material for people of all classes and all times, and a common image in traditional Korean painting, for instance. Indeed, Damyang County supported the installation by donating the bamboo because county officials saw the cultural value of using it for this millennial celebration.

Ma’s vision grows from his Jeolla-do roots, but it is not limited by those roots. The three colors suggested a traditional Korean fan to me, as do the three lower sections of the installation, but the colors that run through and between the different sections show that the tradition is not static. Ma notes that those colors melted into many East Asian areas from ancient to contemporary times, from Siberia to Mongolia and Korea. Thus, those colors show a connection that crosses borders, just as they cross between the areas of the installation.

The entire work, especially with the multiple angles created by the not-perfectly-plumb and not-perfectly-level straight pieces and the multiple circles placed at many different angles, seems to flow outward from the supports tied to the stairway. At the same time, however, from another viewing position, the colors seem to rise from the floor, through the supports, and to the stairway. That back-and-forth, up-and-down flow recalls the Heaven and Earth of millennial Jeolla-do. Because of the constraints of the space, with the partial ceiling and a false wall blocking some of the open space, it is impossible to view the whole installation at once. A viewer must move around and through the installation to view it from different angles in order to imagine its wholeness. I encourage readers to do just that. The installation will be in the museum until November 11.

How to Get to the Museum:

By bus:

– Yongbong 83 or Sangmu 64 to Gwangju Biennale Hall

– Moonhong 48, Songjeong 29, Sangmoo 63 to the old Jeollanam-do Office of Education

By car: Use the Biennale parking lot. Turn right toward Jungoe Park from the Seogwangju IC exit.

Museum Hours: Daily 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., and until 8:00 p.m. on the last Wednesday of every month.

The Author

Robert Grotjohn teaches American literature and popular culture in the Department of English Language and Literature at Chonnam National University and is a former editor-in-chief of the Gwangju News.