What is Thrasher?

Written by William Urbanski.

The one-time symbol of skateboard counterculture has become a ubiquitous fashion logo in Korea and beyond.

If you have functioning eyes, you have no doubt come across the Thrasher logo that has become emblazoned on all sorts of shirts, sweaters, and hats from Myeongdong to Mokpo. While I assumed that most people had an idea that Thrasher had something to do with skateboarding, when an elementary school girl showed up at my work wearing a Thrasher sweatshirt and admitted she had no idea what it was, it was clear that my assumption was flawed. So, what is Thrasher anyway, and why is it the latest “core” brand to be expropriated by the masses?

A Brief History of Skateboard Magazines

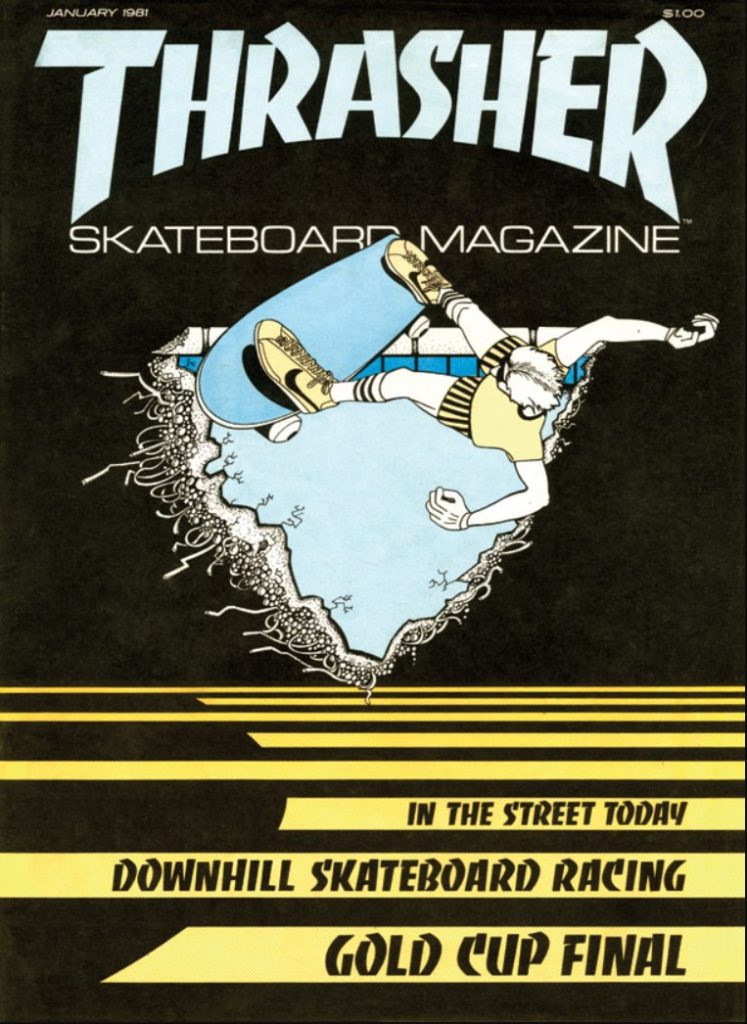

Thrasher is the name of a skateboard magazine that started in 1981 in the San Francisco area, and that highlighted the renegade, outsider, dare I say “outlaw,” faction of skateboarding. When I first came across the magazine around 1995, I was blown away by its depiction of gnarly, underground, core skateboarding and by its “devil may care” image. Thrasher, especially at that time, focused on the hard-charging, punk rock-inspired, gritty stunt kind of skateboarding. While over the years, Thrasher (it is still available in print) has somewhat softened its image, it is still the bastion of the “skate or die” / “skate and destroy” subculture within the larger “skateboard community.” Today, being named Thrasher’s Skater of the Year (SOTY) is the highest honor any skateboarder can receive and is so coveted that professionals and their sponsors actively campaign for it. Thrasher’s legacy and ongoing impact on skateboarding is undeniable, and today it is even colloquially referred to as “the bible.”

While Thrasher is the skate magazine that has best stood the test of time, it is far from the only one that has ever existed. Transworld magazine was a long-running and fantastic publication that I feel best captured the overall ethos of skateboarding. It covered a wider spectrum of skateboarding, had a much broader focus, and featured interviews and articles that are still embedded in my memory over 20 years later. While Thrasher was printed on lower-quality paper and often featured photos that looked like they were taken on disposable Kodak cameras (remember those things?), Transworld had a much more polished feel and featured stunning pictures that not only captured the trick, but the zeitgeist of the era. As well, Transworld emphasized the subtler and more stylish aspects of skateboarding, things that were not easily understood by anyone who could not tell the difference between a nosegrind and a crooked grind. Unfortunately, despite content that constituted the narrative to my teens and early twenties, Transworld’s print magazine went out of publication in 2019 and now exists only as a shell of its former self via www.skateboarding.com and an Instagram account (with a respectable million-plus followers).

Thrasher and Transworld were the two best-known skateboarding magazines, but SLAP and Big Brother are two others worth mentioning. SLAP was probably my favorite magazine and was just an all-around treat to read. The editing team had a clear, and I would say correct, idea of what good skateboarding was and either found or created content in line with that vision. The photography was on point and the level of tricks was insane, all without having the “corporate” feel of Transworld and later iterations of Thrasher. Overall, SLAP had the feel of a ground-level, organic magazine.

On the other end of the spectrum (or lying completely out of the spectrum, for that matter) was Big Brother, which for all intents and purposes, was a little closer to a smut mag than a skateboard chronicle. The story of Big Brother is hilarious, and the magazine was basically run by industry outcasts who wanted nothing more than to stick it to the man. Big Brother was also the medium that spawned the Jackass franchise, so you can imagine what kind of other purposefully scandalous content was in the magazine. On a side note, Big Brother was owned by the notorious publisher Larry Flint.

Out of the “Big 4” magazines of my youth, only Thrasher has truly stood the test of time. Big Brother just kind of disappeared, and while Transworld and SLAP still exist online and produce original content, neither is well-known outside of the skateboard community, and they certainly have not penetrated the mainstream consciousness.

So, why did Thrasher endure? My personal theory is that there are two main reasons. First, as mentioned before, Thrasher’s content was never over-polished. It was and remains gritty while also being easily relatable and understandable. Even outsiders can look at Thrasher and say to themselves, “Oh yeah, I got it. I understand what skateboarding is all about,” despite not being able to distinguish between a kickflip and a heelflip. The second reason is that in the late 2000s, when a great deal of skateboard content went digital, Thrasher (and, by extension, www.thrashermagazine.com) absolutely killed it in terms of pumping out content. By comparison, Transworld’s non-print media content focused on cinema-style, full-length features that I feel came off as overly contrived and artsy, alienating a core part of their target demographic. Thrasher, on the other hand, managed to come up with shorter, more intense videos that, while lacking the professional, even Hollywood feel, of full-length video productions, maintained the “skate or die” spirit of the magazine. By being the skateboard magazine that most successfully navigated the transition to the digital world, it was only really a matter of time before models, singers, and actors started wearing Thrasher.

The Dark Side of the Flaming Logo

That is all well and good, and Thrasher should be commended for staying relevant after all these years. But before people rush out and drop a hundred thousand won on a hoodie with the flaming logo, they should understand that the magazine and the people behind it are not the “be all, end all” of skateboarding and have a pretty substantial dirty underbelly.

Through the years, Thrasher regularly blacklisted skateboarders, banning them from ever appearing in their pages, drastically impacting that skater’s chances of having a successful career. The reasons are myriad but included offenses such as riding for the wrong sponsor, quitting the wrong sponsor, doing the wrong tricks, wearing the wrong gear, not skating the way the editors wanted, or just angering certain people in the industry. While I suppose it is well within their purview to exclude whoever they want, it goes to show that Thrasher sees itself as the gatekeeper of what is real, legitimate skateboarding and what is not. To this day, Thrasher positions itself as the ultimate authority in skateboarding and, through its exclusive practices, imposes its prescriptive vision onto skateboard culture.

Incidentally, while a lot of people are drawn to skateboarding because of its apparent lack of rules and structure (such as coaches and regularly scheduled practice times), it is worth mentioning that skateboarding has standards and norms that for the most part are tacitly adhered to. That is to say, you cannot just pick up a board, twirl it around your arm, and then call it a trick. There are certain techniques that can and should be mastered, and to overlook these, to use the parlance, would be “wack.” In addition, while there is no uniform (except for the Olympic skateboard teams, I suppose), there is certainly a dress code of sorts. So yes, there are standards and norms within skateboarding, but Thrasher seems to take this stuff to a whole new level and acts as basically the fashion police of the entire industry.

Inextricably linked to the physical publication was Jake Phelps, the figurehead and ringleader of the entire operation and the long-term editor-in-chief of Thrasher. A one-time amateur skateboarder in the ’80s, “the Phelper” was among the most well-known people in skateboarding and the walking symbol of all things Thrasher until his untimely death from completely preventable substance abuse in 2019. While it is not my common practice to speak ill of the deceased, I think it is important to point out that the Phelper was an all-around windbag and imbecile with the brain power of a watch battery who could barely string together a sentence not peppered with profanities and obscene references. To see him on the street, one would have easily concluded that he was a crazy homeless person, and Thrasher’s celebration of his antics was curious to say the least.

The last thing to understand about Thrasher is that for many, many years, there was basically a rule that could be succinctly articulated as “Don’t wear Thrasher if you don’t skate,” a mindset encouraged by the magazine itself. Anyone who wore any clothes or gear with the magazine’s logo would be opening themselves up to unrelenting ridicule unless they could ride a skateboard with a reasonable level of proficiency. Elementary school girls and models wearing Thrasher just was not to be done.

Thrasher Korea

When I am out skateboarding or walking around Gwangju and see some Thrasher beanie-wearing fashionista who clearly knows nothing about riding a stickwheel, I really have to scratch my head. For everything Thrasher is, something it is not is a corporate brand that is in line with the values that most Koreans adhere to, such as, you know, getting a good education or respecting group harmony.

All that being said, the old rule of “don’t wear Thrasher if you don’t skate” summarily died the moment www.thrashermagazine.com went online. While still a quality magazine, Thrasher is definitely not the symbol of the hardcore demographic it once was. If you want to wear Thrasher, I say go for it. As for Thrasher, which is no-doubt raking in the big bucks from licensing agreements, they might consider changing their slogan from “Skate and Destroy” to “You Gotta Sell Out to Eat Out.”

THE AUTHOR

William Urbanski is the Gwangju News’ managing editor and its special skateboarding correspondent. Instagram: @will_il_gatto