Who Is Mark Gonzales?

By William Urbanski.

One of the freshest and most surprising fashion brands to be making inroads into the Korean market lately is Mark Gonzales. The brand, which takes its namesake from professional skateboarder Mark Gonzales, seems to be focused on producing lifestyle (or some may say “streetstyle”) clothes that feature his autograph and cartoon bird logo. Many eponymous brands like Versace or Christian Dior invoke a certain sophisticated elegance or mystique – words that definitely do not pop into my head when I think about “the Gonz.” While a household name in the skateboard world, he is still relatively unknown in the mainstream, which is why it is time to pull back the curtains and find out who Mark Gonzales really is.

The Big Names in Skateboarding

When people think of skateboarding, there are usually two names that spring to mind: Tony Hawk and Rodney Mullen. No doubt, the familiarity of these names comes from the Tony Hawk Pro Skater video game franchise and to some degree Mullen’s unfortunate TED Talk with around two million views. Tony Hawk is, without question, skateboarding’s ambassador to the world and the most well-recognized skateboarder ever. Rodney Mullen is a tad bit more “underground” than Tony Hawk and made a name for himself first through the freestyle contest circuit in the 1980s and later through his incredible technical skateboarding. In addition to their sidewalk surfing prowess, both Hawk and Mullen are also surprisingly articulate business owners. Besides these two men, there are a handful of other skateboarders whose names have entered the mainstream, such as Daewon Song (who is a hero in Korea) and Ryan Sheckler (whose MTV show Life of Ryan earned him the moniker “Cryin’ Ryan”), but nowhere near the level of Hawk and Mullen.

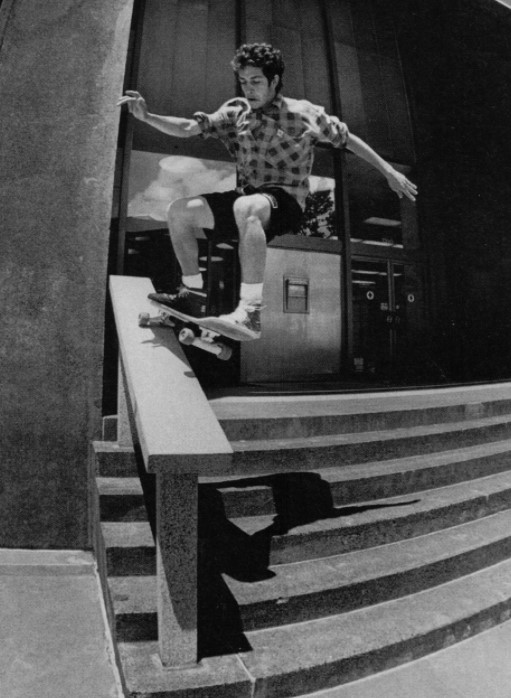

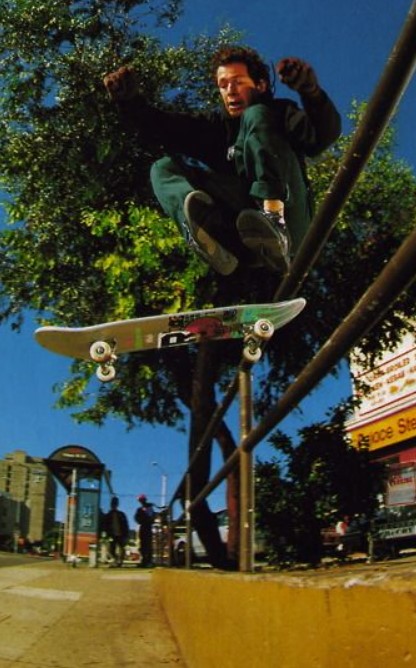

While Mark Gonzales (the man, not the brand) is often overlooked or unknown to the mainstream, he is truly the godfather of modern street skateboarding, and the impact he has had cannot be overstated. When you see skateboarders cruising down the street, flipping their board down stairs or jumping over garbage cans, you basically have Mark Gonzales to thank (or curse, if you happen to be a cantankerous old buzzard). While Gonzales did not “invent” as many tricks as Mullen or Hawk, his creativity and approach to street skateboarding were unlike anything anyone had seen before. In the ’80s, when most “street skaters” were content doing handstands and pirouettes, Gonzales was sliding down handrails and jumping over gaps that were unthinkable at the time and still hold up today. At least one professional skateboarder claimed that seeing Mark Gonzales for the first time was like watching an alien. Truly, if there were a Mt. Rushmore of skateboarding, Gonzales’ weird head would be on it.

An Impactful Career

In the early ’80s, when modern skateboarding emerged from the terrible, banana board-riding, soul-cruising ’70s, there were basically two “disciplines” – transition (including vert ramps and pools) and freestyle. Basically, everyone has seen or is familiar with pool skateboarding and vert ramps, the massive, elongated “U” shaped structures that skaters use to fly into the air. Much less well known, but perhaps equally impressive in its own right, is freestyle skateboarding, in which skateboarders used smaller, skinnier boards to perform routines involving flipping and standing on their boards on flat ground. Hawk and Mullen were each masters of these two domains. As vert and pool skating slowly died out (mainly because it was difficult to find and even more difficult to build and maintain a vert ramp) and freestyle skaters started suffering from unrelenting ridicule for dressing like sissies, there was a void to be filled by “street skating.” While a talented vert skater in his own right, street skateboarding is where the Gonz was, as the youngins say today, an industry disruptor.

Without getting into trick names and skateboarding terminology, what set Gonzales apart was the way he was able to make use of the whole spectrum of everyday objects, including stairs, ledges, benches, and rails spontaneously and intuitively in a way that made them look like they were specifically designed for skateboarding.

Mark Gonzales was basically the right person doing the right thing at the right time and pretty much the entire skateboard industry fell in love with him. To this day, to speak ill of him or his skateboarding is tantamount to heresy. Fortunately for me, I do like his skateboarding in addition to appreciating the impact he has had.

A Strange Dude

On top of his influence as a skater, in terms of securing sponsorship deals, endorsements, and career longevity, the Gonz’s success as a professional skateboarder is undeniable. He has ridden for the biggest companies in skateboarding and has been part of the Adidas skateboard team since before huge corporate brands being involved in skateboarding was even a thing. What is also undeniable is that Mark Gonzales is a very strange dude. Not necessarily weird in a bad way, but let us just say you would not confuse him for a Rhodes Scholar.

While raw talent and guts are the prerequisites to a career as a pro skater, what is less understood is that any prospective pro needs to possess an “x-factor”: a certain “je ne sais quoi” that sets himself apart from the rest. For Mark Gonzales, this x-factor was his art projects and, especially toward the end of his career in earnest, he was well known for the funky pictures he would produce. Now, full discretion: I know next to nothing about art or the art world. That being said, I really do not see what was so special about his wild doodles, and his art is the point where my interest in and appreciation for his talents come to a screeching halt.

From the Streets to the Mainstream

Given how important a figure he is in the skateboard world, it is interesting to speculate as to why, until quite recently, Gonzales never had the mainstream appeal of Hawk or Mullen. I am sure there are myriad reasons, but my hunch is that for many years nobody was going to ever back this guy because he comes off as a complete lunatic. Just go on YouTube and listen to the super weird way he talks for 30 seconds. Everything he says is like an imitation of someone else’s voice and he is constantly muttering nonsense. Entertaining for sure, but not exactly fodder for a sophisticated audience.

The other, less obvious reason has to do with the insular nature of skateboarding. Even though skateboarding is more common and accepted now than ever before, it is still, as a poet such as Walt Whitman might say, “a river with strong currents of counter-culture and a rejection of mainstream values.” These sentiments were even stronger throughout the ’80s and ’90s, and success as a skateboarder, especially as a “street skater,” meant embodying this recalcitrant attitude. That is to say, the very factors required to have a successful pro skateboarding career precluded fitting into the view of what was acceptable to the mainstream. It was either you were a skater or a tool of corporatist society: There was no either/or. In short, there was no way for the Gonzales of yesteryear to front a major corporate brand without compromising his legitimacy as a skater.

But the Gonzales of today is a Gonzales that is far, far past his prime. He is being marketed as more of an artist (which he ain’t) and less as a former pro. Remember that opening a business on this scale is not just a bunch of bros who chip in a few bucks each: It requires massive cash injections and nobody is going to put up that kind of cash to back someone if he is just too weird. Gonzales “the skateboarder” would have been toxic from a large-scale marketing standpoint, but Gonzales the artist who used to be a pro skateboarder is just edgy and cool enough. In short, Gonzales was and is such an “out there” character that until there was enough time between him and his skateboard career, he just was not a good candidate for mainstream appeal.

Conclusions

I was actually quite surprised when I first learned that this brand has not only a Korean website but also a couple of brick-and-mortar stores in Seoul. Upon further reflection, I think Mark Gonzales might just be a good fit for the Korean market. It is weird without being offensive. This innocuous image is key where grown men regularly send emojis of teddy bears holding hearts to their girlfriends. As for the actual clothing, besides being a little more colorful and zany than the standard T-shirts you would find at Big 10, I do not see what the brand is doing to really innovate, but then again, while having impeccable taste in clothing, I am no fashionista.

So, now you know a little about the man, the myth, and the soulless corporate entity that is using his name for a fast buck. All that being said, I think it is a cool brand, and I have schemes in the near future that involve dishing out some serious won on some shirts with cartoon birds on them. While some may criticize me for describing Mark Gonzales as an insipid corporate trademark while simultaneously backing his brand, I would refer them to Walt Whitman’s famous quote: “If I contradict myself, so be it. I contain multitudes.”

The Author

William Urbanski is the Gwangju News’ managing editor and its special skateboarding correspondent. Instagram: @will_il_gatto