Applying Oriental Thought to Korean Life

Arranged by David Shaffer.

In our January issue of the Gwangju News, we brought you an article on “The Year of the Rat” that touched on the Five Elements, yin and yang, and predictions for the year. In this article, based on two past Gwangju News articles by Prof. Shin Sang-soon (1922–2011), “The Way Koreans Apply Oriental Thought to Their Life” (August 2006) and “A Nation Full of Fortune-Tellers” (February 2006), we bring you more on the influence of the Five Elements, yin–yang, and fortune-telling in general on the lives of Koreans. — Ed.

According to the ninth century I Ching, the Book of Changes, the teachings of which are widely practiced in Korea, the Taegeuk (태극, 太極), the Ultimate Limit, was the very substance of the universe before it was divided into heaven and earth. The division was created by two cosmic forces, the yin and the yang, emanating from the Taeguk. Yin and yang (eum/음 and yang/양 in Korean), in turn, exert their influence upon the O Haeng (오행, 五行), the Five Elements, which are considered to be the components of a myriad of things in the universe.

The Five Elements

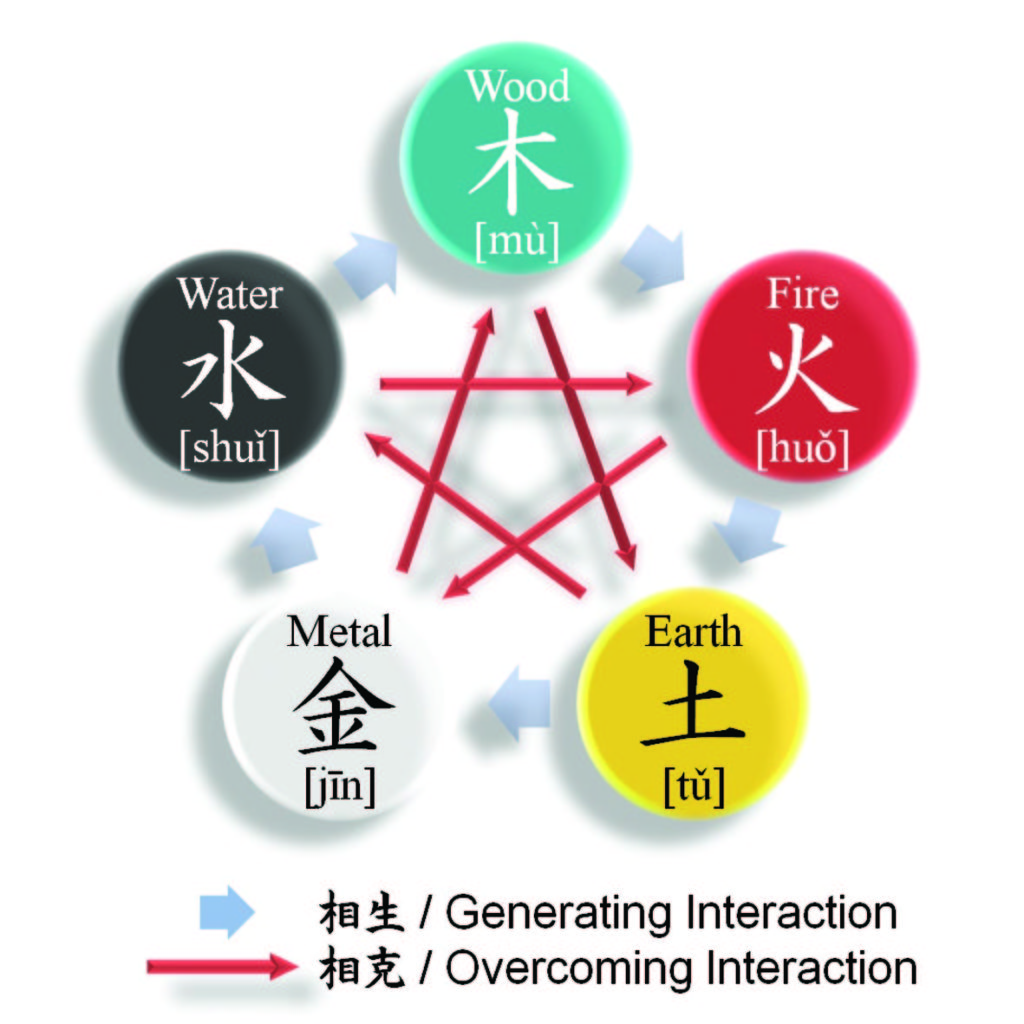

The Five Elements are metal, water, wood, fire, and earth (soil). In creating a plethora of objects and phenomena, the yin and yang forces influence these elements by means of two principles: one of generating, the other of overcoming. According to the generating principle, metal generates water, water generates wood, wood generates fire, fire generates earth, earth generates metal, and so on in a cyclical process of generating. On the other hand, the overcoming principle states that metal overcomes wood, wood – earth, earth – water, water – fire, fire – metal, and so on in the circular process of overcoming.

The two elements in each phase of the generating process are considered harmonious, well-matched, congruous, and compatible. On the other hand, the two elements in each phase of the overcoming process are considered inharmonious, ill-matched, incongruous, and incompatible. Accordingly, Koreans attempt to properly apply these desirable or undesirable combinations of elements in their lives.

Korean Name-Making

When two men with the same surname meet, after passing the time of day, they may ask about each other’s generational character, which may also be one of the characters in their name, to ascertain their family-lineage relationship. If one is found to be one or two generations higher than the other in the lineage order, then the mode of speech of the latter may change to an honorific mode from the peer-to-peer mode that they had been using, even though they may be the same age and even if the latter is older.

Korean given names usually consist of two Chinese characters, one of which is the generational character (dollim-ja, 돌림자), indicative of his generational position in the family lineage. (Here family refers to all those with the same surname, or to sub-groups with the same surname but different locations of origin.) The generational character usually has to do with male lineage only since girls, once married, were regarded as being part of their husband’s family. Each generational character must carry a radical that signifies one of the five elements. The order of the radical-carrying characters must conform to the order of the Five Elements [金(금), 水(수), 木(목), 火(화), 土(토)]. Accordingly, each family surname (or sub-families within the same surname) will have a distinct set of 10 or 15 generational characters that are used cyclically in creating names for offspring of successive generations of the family.

Following the generating principle of the Five Elements, if the grandfather’s generational character carries the metal radical, then the father’s generational character must carry the water radical, following the rule of “metal generates water.” The following generation’s character would carry a wood radical as part of its make-up according to the rule of “water begets wood,” and so on. After a cycle of five generations is completed, the same five radicals come around again in the same order but this time as part of a different character to make a different generational character. Usually two or three sets of five generational characters (that is, 10 or 15 characters) are designated before the same character in the cycle repeats itself. Also, each generational character level may have one, two, or three characters to choose from – all with the same radical. All these character decisions are made by the grand clan and followed from generation to generation.

An example may be helpful. President Moon Jae-in is a member of the Nampyeong branch of the Moon family. Moon Jae-in’s name (문재인) written in Chinese characters is 文在寅. The second character, jae (재, 在), is the generational character in his name. It was one of three that could have been chosen from for his generation – all of which contained the earth element, to (토, 土). You will notice that the lower right portion of the jae character (在) is the earth radical (土). The generational character may be the first or second character of a two-character given name.

Following this system of name-giving is to maintain a harmonizing effect by keeping the forces of the universe in balance, thereby minimizing the possibility of misfortune befalling the individual and the family. Individuals are known to have their names changed, using an alternative character designated for their generation, in order to improve upon their adverse state of affairs.

Match-Making

Another example of the application of yin and yang and the Five Elements is to the matter of marriage. The traditional Korean belief on life was that one’s fate is dependent upon one’s saju palja (사주팔자; literally, “four pillars and eight characters”). The four pillars are the year, month, day, and hour of one’s birth, and the eight characters are the four sets of two Chinese characters representing each pillar. The combination of each set of two characters is based on the Ten Heavenly Stems and Twelve Earthly Branches or the oriental zodiac (see January 2020 issue).

One’s birth is analyzed in terms of the Five Elements. So if the prospective bride’s and groom’s births are of, say, metal and water, or any of the other generating combinations, the two are a good match because their elements are harmonious and compatible. On the other hand, if their births are of, say, metal and wood, or any of the other overcoming combinations, they are unlikely to make a good pair because their elements are inharmonious and incompatible. The forces of yin and yang are believed to be everywhere, opposing and balancing at the same time, thus keeping harmony in the universe.

A Nation Full of Fortune-tellers

When walking through the alleyways of Korean cities, you are likely to encounter a building with a “Hall of Philosophy” (철학과) sign, or a saju palja (사주팔자) sign, or some similar fortune-telling sign. They are the establishments where those who feel insecure about their future go to have their fortunes told by a fortune-teller. The fortune-teller may be either male or female.

Upon entering the “Hall of Philosophy,” one is asked by the fortune-teller for the saju, the “four pillars” of the person whose fortune is to be told, that is, the year, month, day, and hour of the person’s birth according to the lunar calendar. Using one’s saju palja, the fortuneteller, who is usually steeped in Chinese cosmology, consults ancient books of divination, which were based on the I-Ching and provide insight into the cosmic and social changes that affect mankind.

The New Year season, either solar or lunar, is traditionally a time for checking one’s fortune, and that of family members, for the coming year. Fortune-tellers, armed with a book entitled Tojeong Bigyeol are a common sight at traditional markets, street corners, bus stops, and other places where people tend to gather. Tojeong Bigyeol (토정비결; literally, “Tojeong’s secrets”) is said to have been written by Yi Ji-ham (1517–1578), a Confucian scholar whose penname was Tojeong. Walking along a street, you can easily encounter those ubiquitous street-corner fortune-tellers and casually ask them to tell your fortune for the year for an inexpensive fee.

The peak seasons for fortune-tellers are the New Year, school admission exam periods, spring and autumn wedding seasons, and election periods. Since there are so many people and so many curious minds, fortune-tellers’ customers are not in short supply at other times of the year either. This on-going trend of fortune-telling is contrary to the logic of science but, nevertheless, thrives as a “future-predicting industry.” According to an estimate by the Korea Association of Fortune-Tellers, the annual income from the industry amounts to two trillion won (nearly two billion US dollars) – an astronomical figure!

The Korean fortune-telling websites on the Internet number over 150. The annual earnings of one particular site amounts to five billion won (nearly five million US dollars), and it was rumored that the site owner would list his business on the KOSDAQ venture market. In certain districts of Seoul, especially the thriving Gangnam area, there are some 70 fortune-telling shops or cafes equipped with the oriental and occidental tools of the trade and price lists of the plethora of fortune-telling methods they provide.

To mention a few popular cases of fortune-telling, a mother with a son or daughter who is planning to take the college entrance exam may go around to several fortune-tellers, even though she receives a favorable prediction from the first fortune-teller. She may visit a second or third one to confirm that the first prognosis was correct. The way the mind works is that once you hear favorable words, you want to hear more of them.

In cases of elections to various public offices, including those for the National Assembly and local governments, the most anxious people are politicians, or rather their wives. They frequently seek out fortunetellers’ advice as to the advisability of their husbands running for the National Assembly, from which constituency, etc. This seems to indicate that more faith is placed in fortune-tellers’ predictions than in political analysts and consultants in planning for an election campaign.

In addition to charging fees for their services, most Korean fortune-tellers also sell paper talismans (bujeok, 부적), which may cost anywhere from 10,000 won to more than 1 million won (1,000 US dollars). One fortune-teller in Seoul’s affluent Gangnam district was quoted as saying that some 70 percent of his customers buy talismans. Once purchased, talismans are pasted above doorways, placed under pillows and mattresses, and carried in purses and wallets.

When times are dark and favorable outcomes are doubtful, one resorts to fortune-telling. It thrives in places where uncertainty abounds. The Tojeong Bigyeol, the I-Ching, the Five Elements, the yin and yang – all interact to bring harmony and balance to the universe and peace of mind to the Korean psyche.

THE AUTHOR

David Shaffer is a long-time resident of Gwangju. In 2020, he is spending his fifth Year of the Rat here. He has written about lunar calendar and Lunar New Year customs in Seasonal Customs of Korea (Hollym). Dr.Shaffer is the chairman of the board at Gwangju International Center and the editor-in-chief at the Gwangju News