Hot Dog! It’s Summertime in Korea

By David Shaffer.

Western Astrology

The “dog days of summer” is a familiar term that many of us quickly associate with the hottest and most humid period of the summer season. Fewer probably know that this period has traditionally referred to a specific span of time. According to Greek astrology, the dog days begin with the appearance of Sirius, the Dog Star, in the early morning sky and last until it is no longer visible. This year, that period is the 30 days from July 21 to August 19 according to Hellenistic stargazing; however, the dates and the length of the dog days vary in Western cultures: from 30 to 60 days and from early July to early September.

Now what is the association of the star Sirius and “dog”? The connection goes back to astrology: Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky, and it can be found to the left of Orion’s belt. The constellation Orion is also known as “The Hunter,” and Sirius is part of the constellation Canis Major (aka “Greater Dog”), which is located to the lower left of Orion and appears as a dog might when following its master. Outside of ancient astrology, however, the dog days have been associated with a myriad of things disagreeable: heat, lethargy, fever, disease, drought, thunderstorms, mad dogs, and bad luck in general.

The Eastern Tradition

The Far East developed its own version of dog days: three hot days of summer, which were introduced to Korea from Qin China in the 3rd century B.C. The three days are known collectively as Sambok (삼복, 三伏). Interestingly, the character for bok has resemblances to the stellar imagery of Sirius and Orion: the bok character (伏) is made up of the radical for “person” on the left (인, 人) and the character for “dog” on the right (견, 犬) – a dog walking alongside its master. Korea has its own set of particular folk customs, foods, and foretellings associated with Sambok.

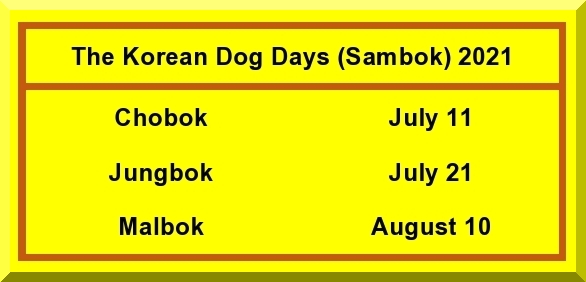

Sambok is three bok days, each of which can be called a bok-nal (복날), but each also has its own name: Chobok (초복) is the first bok-nal, Jungbok (중복) is the middle bok-nal, and Malbok (말복) is the last of the Korean dog days. The procedure for calculating when these three bok-nal occur is a bit complicated, as each involves a gyeong

(경, 庚) day. The ten heavenly stems (천간) are involved in naming each day of the year. Gyeong is the seventh of the ten heavenly stems, so each tenth day is a gyeong day. Chobok occurs on the third gyeong day from Haji, the summer solstice (Haji is one of the 24 seasonal terms that the year is divided into). So, Chobok always occurs 20 to 29 days after the summer solstice/Haji. This year it falls on July 11. Jungbok is the following gyeong day, ten days after Chobok, so it falls on July 21 this year. Malbok is somewhat later; it is calculated as the first gyeong day after Ipchu (the “entrance of autumn,” another of the 24 seasonal terms). Since Ipchu falls on August 7 this year, Malbok is on August 10.

Why a gyeong day, you may ask. Why are all three of the bok-nal on gyeong days? Well, it has to do with the Five Elements (i.e., fire, water, wood, metal, earth). All gyeong days are associated with the element metal. As well, the summer season is associated with the fire element, and since metal is submissive to fire (i.e., fire melts metal), the three bok-nal are associated with an array of misfortune. Activities to be avoided on Chobok, Jungbok, and Malbok included the planting of crops, treating ailments, traveling, and even marriage.

Cool Sambok Customs

As with so many of the holidays of old Korea, the dog days had their associated customs, foods, and prophecies. During the Joseon Dynasty period (15th–19th centuries) and afterwards, it was customary to seek out cool places to shield oneself from the intense heat of the dog days. Many would head for the hills to submerge their paws in the cool waters of one of the many pristine streamlets to be found there. Others would move in packs toward larger streams at the base of mountains to picnic and party in the shade of a riverside pavilion. In the Seoul area, Nam-san and Bugak-san were two popular mountain areas for Sambok relaxation. Those who lived near the coast would race to the seaside for relief from the dog-day heat in the water and the sand. At the sandy beaches, morae-tteumjil (모래뜸질, “sand sauna”) was a great fad. People would lie down in the sand to be completely covered from the neck down by a mound of sand. This would cause the “sand-bather” to sweat profusely, which was believed to eliminate toxins from the body. These sand saunas were believed to be especially effective for those suffering from backache, arthritis and rheumatism, and even neuralgia. Morae-tteumjil was also popular because of the belief that if one took a bath on a bok-nal, they would become emaciated.

As fun as it may sound, morae-tteumjil was not for everyone. Married women on Jeju-do had to be mindful of the belief that if they were buried in sand below the waist on a bok-nal, it could lead to pregnancy! And taking real baths was not for anyone on a bok-nal due to the belief that taking a bath on one of these three days could cause them physical harm of some sort. So, if one did happen to mistakenly bathe on Chobok, they would have to be sure to also bathe on both Jungbok and Malbok in order to avoid any malady or injury due to their Chobok carelessness.

People suffering from gastrointestinal disorders or anemia were more likely to scamper to a mineral spring on a bok-nal. In addition to the belief that mineral water was a great remedy for restoring energy sapped by the summer sun, mineral spring waters were thought to be a cure for stomach ailments and anemic fatigue.

Many are familiar with the custom of washing one’s hair on Dano (단오) with water boiled with changpo

(창포, sweet flag) leaves and roots, but hair washing was also customary on any of the bok-nal. It was believed that washing one’s hair in natural mineral water would prevent strokes, cure skin diseases, heal bruises, and even calm the winds. In the Gangwon area, it was customary to catch spiders on the bok-days. These spiders would then be dried and made into a powder to be used as a remedy for winter colds.

The association of dogs with the heat of summer goes back to long before the Joseon Dynasty – back to the 3rd century B.C. It was then that Korea adopted from Qin China the custom of hanging dog carcasses at the city gates. It was believed that this would not only reduce the foul smells of summer (from garbage heaps, toilets, and open sewers) but also drive away the evil spirits associated with the oppressive summer heat and its related maladies.

Sambok Sustenance

In addition to the summer swelter, dog-day panting was amplified by the expectation of special foods to be served on the three bok-nal. In the royal court of Joseon, high-ranking officials were summoned and served a cool serving of binggwa (빙과), a desert of sugar water and fruit juices mixed with ice from one of the royal underground storage facilities along the Han River, from where the ice originally came the previous winter. Government officials were also given bingpyo (빙표, lit. “ice tickets”) that entitled them to ice from the royal ice bins. But ice and binggwa were summer luxuries only for the elite. For many, patjuk (팥죽), a red adzuki bean porridge, was a bok-nal standard (and still common today on the winter solstice). In addition to its sweet taste, part of patjuk’s appeal was its reddish color. As everyone knew that evil spirits feared the color red, some patjuk was splashed or smeared on the outer walls and the main gate of households to keep away the evil spirits and the misfortunes that they might cause. Bowls of the porridge were also placed in the corners of rooms as offerings to the guardian spirits of the household. (Spirits of all kinds needed to be taken into consideration.) Only after the ceremonial duties had been completed were mere humans allowed to lap up their Sambok porridge.

The two most well-known Sambok foods associated with the three bok-nal over the centuries are stews: samgye-tang (삼계탕, lit. ginseng-chicken stew) and gu-tang (구탕, lit. dog stew). The former has gained in popularity in recent years, while the latter has declined. Both, however, were believed to have restorative properties for bodies weakened by the summer heat and to ward off illness. Samgye-tang consisted of a young chicken stuffed with rice, ginseng, and jujube boiled in a broth, while gu-tang was a stew of greens, onions, and spices along with dogmeat. Gu-tang was considered a stamina food, so much so that it was a dish reserved only for men, and it was especially effective for men who were “dog tired.”

The single main contributor to dogmeat stew’s decline in popularity was the 1988 Seoul Olympics, when the stew was known as bosin-tang (보신탕). The government banned bosin-tang restaurants from conspicuous downtown areas so as not to draw the ire of pet-loving international visitors and media expected for the Games. At the time, dogs were not at all popular as house pets; there was no “puppy love.” Indeed, the only dogs to be seen were watchdogs, usually mongrels, who spent all their lives outside the house. (Cute poodles, Chihuahuas, and Maltese are a more recent import.) To improve their image as well as sales, dogmeat restaurants changed the name of their signature stew to boyang-tang (보양탕), but this did little to bring back the popularity the stew had once enjoyed. International opinion against eating dogmeat was increasing, the love of Koreans for pet doggies was skyrocketing, and the knowledge of how dogs in Korea were slaughtered for their meat became widely known: In order to soften the texture and heighten the taste of the meat, it was common practice to string up the live dog and beat it over its entire body until it died. However, a somewhat recent survey surprisingly found that an estimated 780,000 to 1 million dogs yearly are still consumed in South Korea (Lee, 2017).

Prophetic Predictions

As with other special days on the traditional Korean calendar, there are bok-nal predictions of pending fortune and misfortune. More often than not, these predictions are based on weather conditions. In the case of bok-nal, these predictions were related to dog-day rain, called Sambok-bi (삼복비). In the Jeolla area, rain on a bok-nal was called nongsa-bi (농사비, farming rain) and was considered to be an auspicious sign that there would be a good harvest that year. In general, however, the warm weather of summer was welcomed by the peninsula’s farmers; for them, sunny weather indicated that the autumn would produce an abundant rice crop. To show their gratitude, a dog-day rite called bok-je (복제) was performed by farmers in all areas on Chobok. Rice cakes and pan-fried foods were taken to the rice paddies and offered to the guardian spirits of agriculture, while supplications were made for a bountiful harvest.

In Gangwon Province, farmers feared thunder and rain on any of the three bok-nal as it was an indication that the fruit crops for that year would be very poor. In Chungcheong Province, it was said that the young ladies of Boeun were crying if there was rain on a dog day. Boeun County of Chungcheong was the cradle of jujube production, and rain at this time of year could severely damage the jujube fruit, which could considerably lower the financial status of the families of Boeun’s young ladies of marriage age, which in turn could greatly decrease their chances of finding a suitable marriage partner. So, the damsels of Boeun and the fruit farmers of Gangwon both hoped for no rain on any dog day.

As the saying goes, “Every dog has its day.” In Korean custom, that day would be either on Chobok, Jungbok, or Malbok.

Sources

Hong, S. (1989). 동국세시기 (Dongguk sesigi; A record of seasonal customs in Korea; D. Choi, Trans.). Hongshin Culture.

(Original work published 1849)

Jung, J. (n.d.). 삼복 (三伏) (Sambok). Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture. https://folkency.nfm.go.kr/topic/detail/4130

Lee, K. (2017, September 14). 개고기는 法규제 자체가 없어 뭐가얼마나 들었는지 모른다. Chosun Ilbo. https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2017/09/14/2017091400272.html

Shaffer, D. E. (2007). Seasonal customs of Korea. Hollym.

The Author

David Shaffer came to Korea when having a bowl of boshin-tang for lunch on Chobok was an annual custom among his office workers, and for many years, he lived next door to a bosin-tang restaurant. He has spent approximately 150 bok-nal in Gwangju and is looking forward to spending many more. Dr. Shaffer is the author of the book Seasonal Customs of Korea (Hollym, 2007) and is also the editor-in-chief of the Gwangju News.