The Penal Code in the Joseon Dynasty

Arranged by David Shaffer.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in South Korea, and executions are carried out by hanging. While this may seem inhumane and outdated to some, it does not compare to the severity of sentences meted out during the Joseon Dynasty. Prof. Shin Sangsoon (1922–2011) details in this first part of a two-part article forms of capital punishment and lesser sentences in Joseon Korea. This article was first published in Prof. Shin’s column, The Korean Way, appearing in the November 2007 issue of the Gwangju News. — Ed.

Corporal punishment during the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) was in many ways a carryover from the prior Goryeo Dynasty (935–1392), which took its penal code from the administrative code of China’s Ming Dynasty. With the change from a Buddhism-oriented dynasty to a Confucianism-oriented dynasty, Joseon tried to establish a kingdom based on Confucian ethics, which was followed by the sadaebu (sa = scholar or well-read person; daebu = government official or bureaucrat). They were well educated and knowledgeable, and adept in the administration of government affairs. Their aim was to set up a harmonious and stable society steeped in benevolence with appropriate legal, ethical, and social rules and regulations.

The penal code of the Joseon era, as in the preceding era, was based on five types of punishment: whipping, flogging, hard labor, banishment, and the death penalty. For the first two punishments, a written law regulated the size of the implements used and the procedure for their use to ensure uniform application of the penalty everywhere. A supervisory system was in force to prevent arbitrariness and over-punishment by any penal officer. Offices that had the right to arrest and detain a criminal were specified in the National Code.

A three-tiered review system was required for a death penalty and the offender was executed only with a royal sanction. Criminal laws were provided with compassion clauses to safeguard the offenders’ rights, and kings attached much importance to compassionate administration of penal laws as a symbol of royal benevolence. However, toward the end of the Joseon Dynasty, political corruption, power politics, and the severe persecution of Catholics left an impression of harsh, merciless, and even erroneous administration of the penal code.

Whipping, the lightest penalty practiced since Goryeo times, was divided into categories: from 10 lashes to 50. A fine could be paid for those over 70 and under 15 years of age, pregnant women, and those with serious illnesses. Whipping was kept as a form of punishment long after flogging was abolished at the end of the Joseon period and was finally abolished in 1920.

Flogging was a more serious penalty and the implements used in carrying out the punishment were larger than those for whipping. It was the flogging that was the most maladministered of penalties because there was a lot of room for arbitrariness in flogging on the part of the penal enforcer. So the size of the rod and the method for using it, over time, became strictly regulated by law.

Hard labor was similar to present-day hard labor. The offender was detained in a prison and served for a certain term doing strenuous work. The terms ranged from one to three years and flogging was usually affixed to the hard labor. There were laws punishing any prison officer who committed irregularities regarding prisoners sentenced to hard labor.

Those prisoners who were sent to a salt yard or an iron foundry had to make a certain amount of salt or temper a certain amount of iron every day and remit the wages earned to the government. If there were no salt yard or foundry in the area, they were sent to a paper mill or roof-tile yard, or to a government office to do tasks there. Prisoners were allowed home leave and sick leave. When a parent died, the prisoner was allowed home leave to mourn, and any period of sick leave was later made up after the prisoner’s return to health and to prison.

Banishment was the sentence for offenders of grave crimes, exiling them to remote isolated places and not allowing them to return home until they met their end. Banishment was meant to be a reduced sentence or mitigation of capital punishment which was imposed rather widely throughout the Joseon era and, unlike for hard labor, its term was not set. The convict could only be released from the sentence by a royal pardon. Political strife centering on political hegemony during the Joseon era produced many political prisoners, and those who were spared capital punishment were sentenced to banishment. Political offenders among the banished were provided with foodstuffs and daily necessities by the government. Wives, concubines, and family members were allowed to accompany the prisoners.

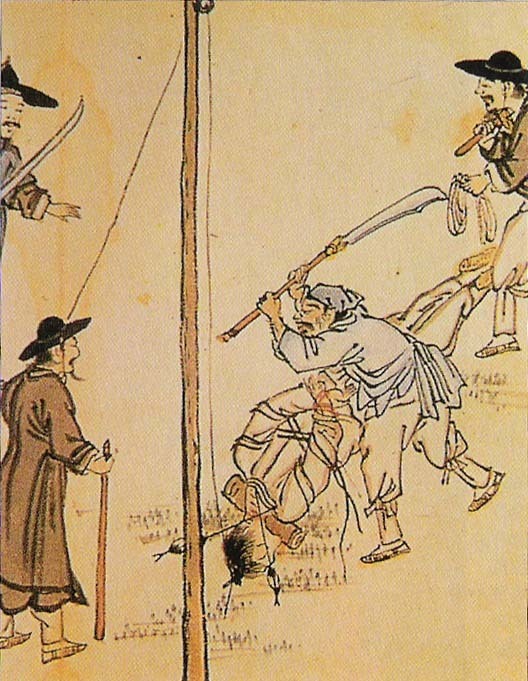

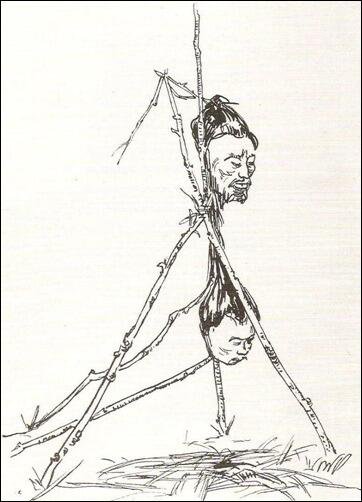

The death penalty, the gravest punishment, was of two types: strangling and beheading, both adopted from the Ming Dynasty Administrative Code. Death by strangulation was by choking and leaving the body intact. Beheading was literally severing the head from the body. Depending on the nature of the offence, the offender was put to death by neungji-cheocham (능지처참, lingering death by slow slicing). Sometimes for the purpose of striking terror into the general public, the head and body were displayed in a public square in a practice called hyosu (효수), hanging the severed head on a pole.

Execution was in one of two time frames: delayed and immediate. The former was applied to ordinary convicts, those who waited for a certain period of time to be executed on a date set between the autumnal equinox and the onset of spring. The latter was applied to those convicted of such grave crimes as rebellion, high treason, insurrection, blasphemy, and unfilial behavior as soon as the death sentence was announced. Of course, the three-tiered review procedure was required before a final royal sanction.

As to the method of execution, the penal code simply stated strangulation, beheading, and neungji-cheocham. The first two were rather simple, but the third was applied mainly in cases of high treason and amorality to give warning to and strike terror into the general public. Execution was carried out as yuksi (육시, dead body severing), osal (오살, death by five severings), geoyeol (거열, body ripped apart by oxen). In the case of yuksi, when the conviction for a serious crime was concluded after the perpetrator’s death, the dead body was decapitated and possibly the arms and legs severed. In the case of osal, five body parts were severed: first, the head; next, the legs; and last the arms. But in more heinous crimes, the order of severing was reversed! Geoyeol consisted of pulling apart the body of the convicted person by having their arms, legs, and head tied with ropes to oxen moving in opposing directions. These methods of execution were so cruel that people shuddered at the mere mention of them, and these terms came to be used in cursing.

In addition to these forms of capital punishment, there were two very unusual death penalties: sasa (granted death) and bugwan-chamsi (부관참시, beheading of exhumed body). The king could benevolently grant that death be by sasa (사사) by giving the convicted a deadly poison to swallow. This was applied to royal families and high-ranking officials involved in treason. Bugwan-chamsi was a kind of posthumous “execution” that could be carried out when the commission of a serious crime was revealed after the perpetrator’s death: The body was exhumed and decapitated, and the limbs could also be severed. Two such cases occurred during the Joseon era as a result of court intrigue and political strife. They were intended as a show of hatred and rage by the king.

[We hope you return next issue for more on the Joseon era criminal sentences.]