Shamans in Korean Supernatural Thrillers

By Régis Olry

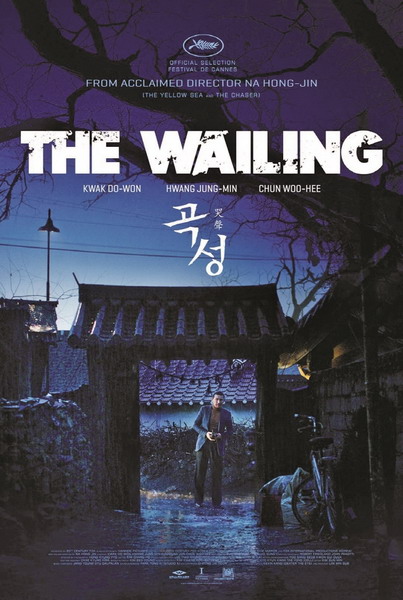

Shamans are pivotal figures of Korean folklore and cinema, but they also remain, still today, a societal phenomenon: 38 percent of the total adult population in South Korea admit they have hired a shaman at least once.1 Many movies contain a shaman fighting more or less successfully against evil creatures (ghosts, demons, or even the devil himself). In my opinion, the most impressive and, above all, most convincing shaman of Korean cinema is to be found in Na Hong-jin’s 2016 supernatural thriller The Wailing (곡성, Gokseong), an absolutely unmissable movie for whoever is interested in Korean culture.

The Wailing

In Gokseong, a peaceful, rural village of South Jeolla Province, the inhabitants suddenly start killing each other for inexplicable reasons. A Japanese called “The Stranger” (Kunimura Jun, 國村 隼) who recently settled in the neighboring forest, is suspected of being involved – though nobody knows neither why nor how – in these gruesome murders. A mysterious woman in white referred to as “The Anonymous Woman” (Chun Woo-hee, 천우희) appears here and there without us exactly knowing who she is (a ghost according to some critics, the angel Gabriel in my opinion). One day, police officer Jong-gu (Kwak Do-won, 곽도원) realizes that his own daughter Hyo-jin seems to be possessed by “The Stranger.” The physicians have no idea what is happening; reluctantly, Jong-gu finally agrees to hire renowned shaman Il-gwang (Hwang Jung-min, 황정민). The latter rapidly acknowledges the gravity of the situation and recommends exorcisms and powerful rites that unfortunately fail to free the young girl. Hyo-jin finally kills her whole family, “The Stranger” proves to be the Devil, and “The Anonymous Woman” understands that she has lost the battle against him, who from now on possesses the shaman.2 This real masterpiece is a good opportunity to get into Korean shamanism.

Korean Shamanism

Shamanism, broadly speaking, has its principal roots in Siberia,3 but shamans (mudang, 무당 or mansin, 만신) are nowadays found almost all over the world: “Outside Europe, we would be hard pressed to find an area of the world that did not have some form of shamanism.”4 Like all religious/spiritual phenomena, shamanism unfortunately has its black sheep who pretend to get rid of all kinds of evil spirits in exchange for a generous amount of money. In the early twentieth century, Robert J. Moose, who lived in Korea in the early 1900s, wrote that “There is probably no other class of women in the land that makes so much money as do the mudangs.”5 But let’s look only into a kind of shamanism we consider as “ethic,” without of course pronouncing for or against its effectiveness.

What Is Shamanism?

To define shamanism defies definition.6,7 To cut a long story short, I could say that a shaman is someone able “to transcend the barrier between the two worlds”8 in order to help clients through various rituals (referred to as kut, 굿), often with the help of many accessories, including, for example, a pig’s head, into the orifices of which will be inserted some bank notes. The meaning of the colors of the clothes worn by the shaman and her clients are also of outstanding importance: Thin, yellow cloth is an offering for wandering ghosts (the hold of them being broken when the cloth is ripped), and a green flag indicates that one is followed by a restless ghost.

How to Become a Korean Shaman

It should first be pointed out that the greatest portion of Korean shamans are female,9 a characteristic shared by neighboring countries such as China10 and especially Burma where over 95 percent of shamans are females.11 As for the decision to become a shaman in Korea, it is not yours: Shamanism is either “hereditary” (seseup mudang, 세습무당) or “destined, initiated” (gangsin mudang, 강신무당), the training process of both being quite different.12 A hereditary shaman learns the basics (shaman songs: muga, 무가) from her mother and, after getting married, she goes deeper into various shamanistic rituals with the help of her mother-in-law whom she will be bound to gradually replace. A destined shaman is selected by the gods of shamanism through a sickness known as sinbyeong (신병) or mubyeong (무병; mysterious dreams, weakening of the body, strange eating behavior, visual and auditory hallucinations), which she will be cured of only if she accepts becoming a shaman through an initiatory ritual (naerim kut, 내림굿).

What Kind of Powers Is a Shaman Supposed to Have?

The “powers” of a shaman are multifaceted. In accordance with a client’s expectations, they can be a clairvoyant (during the first two weeks of the lunar year, many of them are consulted by “women to get a prognosis on each member of her family”),6 an exorcist (shamans are able to differentiate between beneficial and harmful spirits, and to expel the latter from people or houses they possess), or a medium (after having fallen into a trance to the sound of a drum, the shaman can speak on behalf of gods, ghosts, or ancestors who possess the clients). Of course, Korean shamanism would deserve much more development…

References

- Kim Chongho. (2003). Korean shamanism. The cultural paradox. Ashgate.

- The Wailing. A film by Na Hong Jin (2016). Promotional booklet.

- Eliade, M. (1964). Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy. Pantheon.

- Kendall, L. (1984). Korean shamanism: Women’s rites and a Chinese comparison. Senri Ethnological Studies, 11, 57.

- Moose, R. J. (1911). Village life in Korea (p. 192). Nashville, Methodist Church, Smith and Lamar, Agents.

- Kendall, L. (1987). Shamans, housewives, and other restless spirits: Women in Korean ritual life (p. 74). University of Hawaii.

- Lee, Nami, & Kim, Eun-young. (2017). A shamanic Korean ritual for transforming death and sickness into rebirth and integration. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 7(5), 75–80.

- Blacker, C. (1986). The catalpa bow. A study of shamanistic practices in Japan (p. 21). George Allen & Unwin.

- Kendall, L. (1988). The life and hard times of a Korean shaman: Of tales and the telling of tales (p. 6). University of Hawaii Press.

- Wolf, A. P. (Ed.). (1974). Religion and ritual in Chinese society (p. 10). Stanford University Press.

- Spiro, M. E. (1978). Burmese supernaturalism (Expanded ed., p. 205). Institute for the Study of Human Issues (Philadelphia).

- Pettid, M. J. (2009). Shamans, ghosts, and hobgoblins amidst Korean folk customs. SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies, 6, 1–13.

The Author

Régis Olry, M.D. (France), is professor of anatomy at the University of Quebec at Trois-Rivieres (Canada). In the early 1990s, he worked in Germany with Gunther von Hagens, the inventor of plastination and the BodyWorld exhibitions. He currently studies the concept of Asian ghosts in collaboration with his wife who is a painter (see www.gedupont.com).