The Supernatural: Korean Dragons and Ghosts

Written by Adam Volle and Stephen Redeker.

Arranged by David Shaffer.

Korean folklore is full of the supernatural: flying horses, phoenixes, three-headed fowls, pipe-smoking tigers, prank-playing and evil spirits, and of course, dragons and ghosts of all sorts. We have gone back through our archives to find a duo of very interesting articles on the latter two. Adam Volle writes about dragons and their journey to Korea (“Dragons Are Important in Korean Mythology,” Gwangju News, September 2013), while Stephen Redeker tells us all about “Korean Ghosts” (Gwangju News, December 2012). Have no fear; pure enjoyment is to come. — Ed.

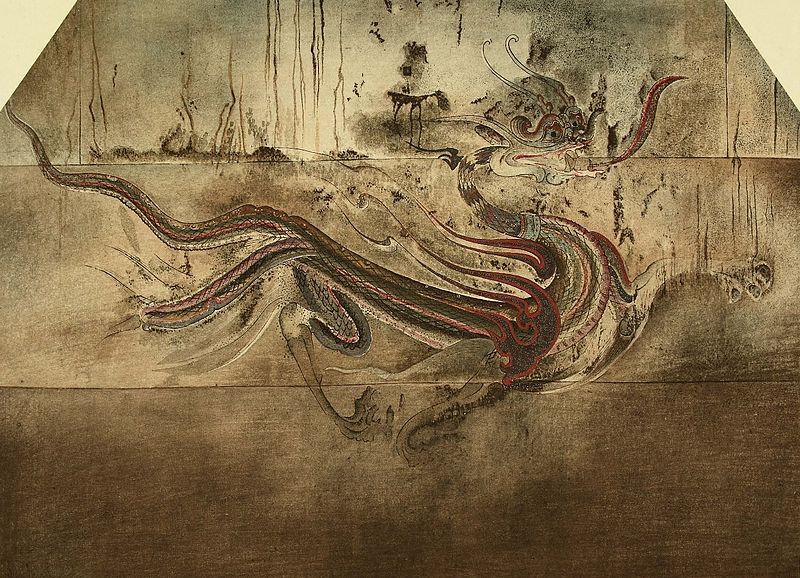

KOREAN DRAGONS

Dragons are important in Korean mythology, so how did they come to Korea? The simple answer is “from China.” Archaeologists have discovered dragon statues in Henan that date back to the Stone Age. The culture that made those statues probably shared the dragon concept with the ancestors of ethnic Koreans.

But China is only the birthplace of the dragon’s appearance and basic associations (power, rain, and luck). To truly understand Korean dragons, look to the birthplace of their stories: India. India is the home of Buddhism, one of Korea’s major religions. India is also the home of the nāga, a spirit that usually takes the form of a king cobra and sometimes that of a human. The nāga can fly but does not make a habit of it for the understandable fear that a bird might attack it. As one of India’s old gods, nāgas have a place in most Indian religions, and Indian Buddhism is no exception.

One famous nāga in Indian Buddhism is Mucalinda, king of the snakes. Legends say that when a storm rained upon the Buddha during his meditation, Mucalinda covered the Buddha with his hood. Afterward, Mucalinda invited the Buddha to his underwater palace and became the Buddha’s first follower.

If you are acquainted with East Asian dragon stories, this story sounds familiar. Chinese, Korean, and Japanese mythologies all have dragon kings who live in underwater palaces. In all three cultures, dragons are also the Buddha’s first believers.

Yes, many Buddhist stories about dragons in East Asia are actually nāga stories. Moreover, every dragon story in Asia is influenced by them. Like the teachings of the Buddha, the stories of nāgas told by Indian missionaries became very popular with Chinese people, and it is not hard to understand how they heard the Indians talk about large, flying snakes and thought they must be talking about dragons.

The misunderstanding greatly changed East Asian concepts of dragons. Before Buddhism, Chinese people understood dragons as controllers of rain, but they did not believe a dragon might live in any river, lake, or ocean. Nobody believed in dragon kings. Dragons certainly did not have the wish-fulfilling orbs, which in Korean are called yeouiju (여의주, dragon ball). The orbs are from an Indian legend about a jewel called the Cirimani.

Most importantly, the job of dragons changed with the Indian influence; they became protectors more than rainmakers. Indeed, dragons even became the guardians of Buddhism’s Three Gems: the Buddha, the Buddha’s teachings, and Buddhist monks. As Korea became a Buddhist land, dragons logically became guardians of Korea itself – and though Buddhism later declined, Korean interest in dragons never has.

KOREAN GHOSTS

What exactly are Korean ghosts? There are precisely four types of Korean ghosts, called gwishin (귀신), which are believed to be the spirits of the deceased who have not been able to fulfill their life’s purpose. They are stuck in the afterlife, still haunting the living, not able to cross over to “the other side,” and waiting for their souls to be appeased. The origins of these spiritual beliefs stem from shamanism, an ancient religion that still has its followers in Korea, which deals with supernatural spirits in the natural world. Numerous shamanistic rituals deal with appeasing these gwishin. Subsequently, there are many Korean horror films that feature ghosts looking like deathly pale girls wearing white gowns. Their lips are blood red and they seem to float on air. This resembles the ghost called cheonyeo-gwishin (처녀귀신).

The cheonyeo-gwishin is the most common of the four types of Korean ghosts. She is the “virgin ghost,” the girl who could not serve her full purpose in life. It was very difficult to be a woman in early Korean times; her life would consist of only serving her father, her husband, and her children. If she had failed in achieving her wish and had lifelong resentment, her life would have been meaningless and her soul would be stuck in our world. This ghost wears traditional white mourning clothes called sobok (소복) and wears her long hair down because she does not have the right to wear her hair up, as married women traditionally did. She holds grudges over those who may have caused her harm and continues to haunt them. The Ring is a film based on an earlier Japanese horror movie that features a ghost such as this.

The male equivalent to the cheonyeo-gwishin ghost is the chonggak-gwishin (총각귀신). Also known as mongdal-gwishin (몽달귀신), he is the unmarried bachelor ghost. Sometimes there are shamanistic rituals that aim to unite these two forms of ghosts, the cheonyeo– and chonggak-gwishin, so that they may be married. If successful, their life would be completed and satisfied (in a spiritual sense). At peace, they may then be permitted to enter the afterworld. In pop culture and films, the female ghost is much more common than the male version.

Some people say drowning is the worst way to die. Well, there is a ghost for that. A mul-gwishin (물귀신) is the spirit of someone who drowned, a “water ghost.” These ghosts are very lonely, living in the cold water where they died, so they may pull the living down into the watery depths if they are not careful. This spirit has led to the Korean term mul-gwishin jakjeon (물귀신 작전), meaning “water ghost tactics.” This expression means that someone is dragging you down so that you suffer along with them; a form of sabotage. It is something like the “I’m taking you down with me” expression.

The ghost named dalgyal-gwishin (달걀귀신) might be the strangest. It is egg-shaped with no eyes, nose, mouth, or even arms or legs. According to legend, if one sets eyes on it, they will die. The ghost has no personality or discernable emotions or origins. This is the deadliest and most frightening ghost. Some say it lives in the mountains and haunts those who traverse its paths.

Another ghost worth mentioning here is the “nine-tailed fox” ghost (gumiho, 구미호). Long ago, it was believed that certain animals could obtain human-like characteristics. This nine-tailed fox is an example, as it could change into a beautiful woman and lure an unsuspecting man to his death (by eating out his liver). This ghost is mainly seen as an evil spirit, but a recent Korean romantic film called My Girlfriend Is a Gumiho (내 여자친구는 구미호) totally changed that image. This film, starring Lee Seung-gi and Shin Min-ah, gives a very cute and bubbly depiction of the gumiho ghost. In the movie, the ghost is trying to have a successful relationship with her boyfriend in order to fully become human!

As in many other countries and cultures, Korea has its share of unique ghosts that have arisen from old beliefs carried down through the centuries. Although not as feared as they were in the past, they still serve their purposes as entertainment and as a glimpse into what people once believed to be true. Now, armed with an education in Korean “ghost lore,” many of these popular Korean horror movies may have more meaning. How about some Hollywood remakes with a few gwishin in the plot? Wouldn’t it be great to see a Korean version of Ghostbusters featuring all of these ghosts?

2 thoughts on “The Supernatural: Korean Dragons and Ghosts”