Round and Around: Drawing an Arc of Korean History Through the May 18 Democratic Movement

Reviewed by Ashley Sangyou Kim

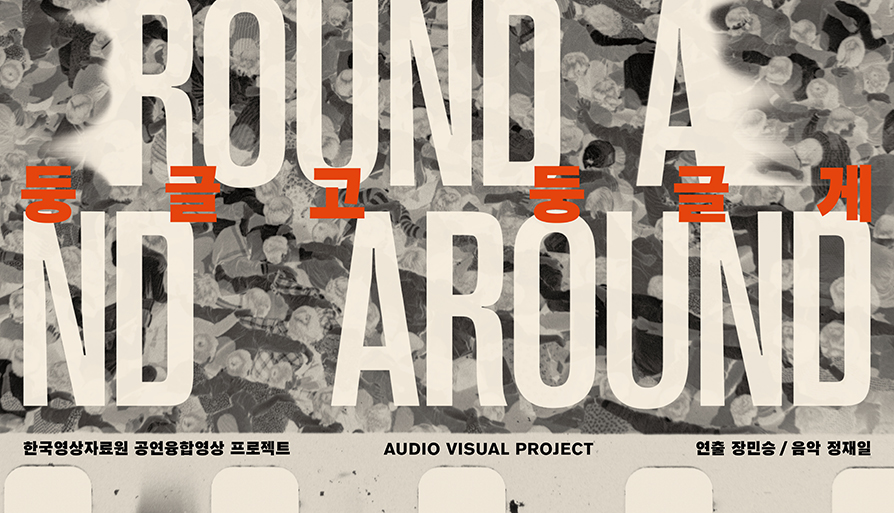

When my film professor introduced Round and Around to me, he furrowed his brows, tilted his head to one side, and ultimately settled on the words “austere” and “abstract.” The official description of Round and Around uses the term “audio-visual project,” and the stated purpose is to “reflect [on] the significance of the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement.” This 90-minute film combines archival footage and photographs with chorus music and amplified sound effects to revisit different moments of state violence in 1980s South Korea. Director Jang Min-seung offers a fractured yet intimate representation of May 18 through an interplay between sight and sound. I will go through some of the thoughts I walked away with from watching this film.

One of the most remarkable things about Round and Around is that it shows how wide the scope of state violence is. State violence can mean neglect after natural disasters, inhumane labor conditions, or the symbolic violence in a false representation of harmony (see Figure 1). All of these events point back to Gwangju, where state violence reaches senseless heights.

Although this film is very specific to South Korean history, it does not require the audience to have previous knowledge on the subject. In fact, the unconventional and abstract style asks those who are familiar with modern Korean history to see the 1980s in a different light. In this film, history is not told through narrative. There is no logical procession from one event to another; although events are shown roughly in reverse chronological order, the footage frequently jumps back and forth between events. The film operates on a rhythm that is at times overwhelmingly fast and at others uncomfortably slow. This mimics how time is felt by the people who live through the history and thereby breaks the critical distance that often accompanies depictions of past events.

Take the two opening scenes, for example. The first is a six-minute-long take of a candle lit in a pitch-black space (see Figure 2). At around five minutes in, the candle is blown out, but the screen stays on the curly white smoke rising from the candlewick. The image of a candle lit and subsequently blown out brings up many questions about who is being mourned or honored and what caused the light to go out. With these thoughts, six minutes do not feel so long. This eerily still and quiet shot cuts to a drastically different second scene, which shows the brutal labor conditions in South Korea’s factories. Here, the clanking of sewing machines and quick flashes of packed factory floors (see Figure 3) convey the orderly chaos that laborers live in. This scene has a quick pace but is long and repetitive, so that time feels fast but moves slowly. Contrast this with the first scene, where time feels slow but moves fast.

The film runs through the 1980s roughly in reverse chronological order, and this movement from the late 1980s to May 18 seems like peeling the layers around a well-kept open secret until it explodes. More specifically, the film’s representation of May 18 feels like a poisonous explosion contained within silence. When the film directly deals with the protests of May 18, loud warning signals and negative photographs suggest that these images are too hazardous and strong to confront directly (see Figure 4). The film brackets this intense representation of May 18 with two solemn scenes before and after it. In these two scenes, long silences and low-humming chorus music express the undercurrent of resentment, fear, sorrow, and numbness that flow around May 18. I found that these moments helped me prepare for and absorb the shock of the photographs.

Round and Around includes curious reflections on many more topics: doubts about the relationship between humans and God, the unreliability of official narratives, time as a linear concept, and so on. Because the film is “abstract” and “austere,” to borrow my film professor’s words, the audience can fill in the gaps with their own thoughts and experiences related to state violence. Watching this film provided me with the mental space to process what remains from the collective trauma of May 18. Round and Around opens this space by refusing to let go of the lost sensory details in state violence – what these events looked and sounded like can point to the contradictions within a state’s promise of a homogenous and harmonious community.

The Reviewer

Ashley Sangyou Kim is a senior at UC Berkeley studying rhetoric. She loves reading Toni Morrison, hiking, and baking with her little sister. She currently lives in Brea, California, but spent her early childhood in Gwangju. Her hope is to return to the city after graduation and work with the youth there.