Chapter 3. Roofs of Gwangju’s Mass-Produced Hanok: Cost Efficiency or New Fashion?

By Kang Dong-su

Last time, we briefly learned how the floor plans of Gwangju’s mass-produced hanok were made and how these traditional Korean houses look. Though the shapes originated from noble or rich people’s houses in Honam, there were a lot of changes made to adapt to the modern period by discarding some elements such as the porch-like daecheong-maru (대청마루) or enhancing functions by making hot water heating systems for most of the rooms. Homes made in L-shapes and long, rectangle shapes were the most dominant. Especially, a lot of L-shaped hanok were built at that time, which previously would have had a nu-maru (누마루), a verenda of sorts, as this design was a symbol of earlier homes of the nobility.

In this chapter, I want to talk about the roof designs of Gwangju’s mass-produced hanok. Roof designs are one of the main symbols of East Asian architecture, and such designs represent many things, depending on the region and the period in which they emerged. Gwangju’s mass-produced hanok styles also tell us a lot of stories about the modern times of Gwangju.

Even among those who are currently working in the hanok or heritage fields, many think of Gwangju’s mass-produced hanok roof designs as ridiculous or too exotic, especially if they are educated or used to Joseon Dynasty styles, so-called authentic traditional Korean designs. Current Korean law also does not regard Gwangju hanok as proper hanok because of the designs of the roofs and rooftile materials, which make them hard to preserve or hard to open as an official “hanok-stay.” But if we get over our prejudice and pay them more attention, we can observe and feel how Gwangju people adopted traditional architectural skills and adapted them in their own way.

Curvy Roof Lines

The first thing we can notice about Gwangju hanok roofs is the exaggerated curvy line on the top, which is called yong-maru (용마루). This line is visually one of the most important components of traditional architecture as it is the first thing we see from the outside. Compared to other regions of Korea, Gwangju and nearby areas have this big curvy line in their roofs that almost looks like roofs in Southeast Asia or in parts of Southern China. A more surprising fact is that this curvy line had never been created before the 1960s in this region – it was simply created in the 1960s and then disappeared after the 1980s. How did this happen, and why did builders suddenly make such a big design change?

The first reason, I suppose, was to make it visually appealing to the masses. Hanok builders in the 1960–1970s had to create new mass-produced hanok that were attractive to buyers who had a fantasy about fancy roof-tiled hanok. So, they elaborated home façades with striking roof designs to appeal to customers. Japanese roof tiles, which were a new modern material at the time, also technically helped to create this design, as traditional Korean roof tiles created too much weight to make the same designs seen in 1960–1970 mass-produced hanok. The second reason is that people in this region have less bias regarding the definition of “hanok” than other regions, as there were never many Joseon Dynasty-style noble houses previously built in the area, and this lesser bias also led to locals accepting many outside influences from places like Japan, China, and even from the Western culture of missionaries. This avant-garde ambiance might have influenced the designs we see today, including the extra curvy roof lines that were acceptable to the Gwangju general public at that time.

The Decline of Craftmanship and the Era of Commercialism

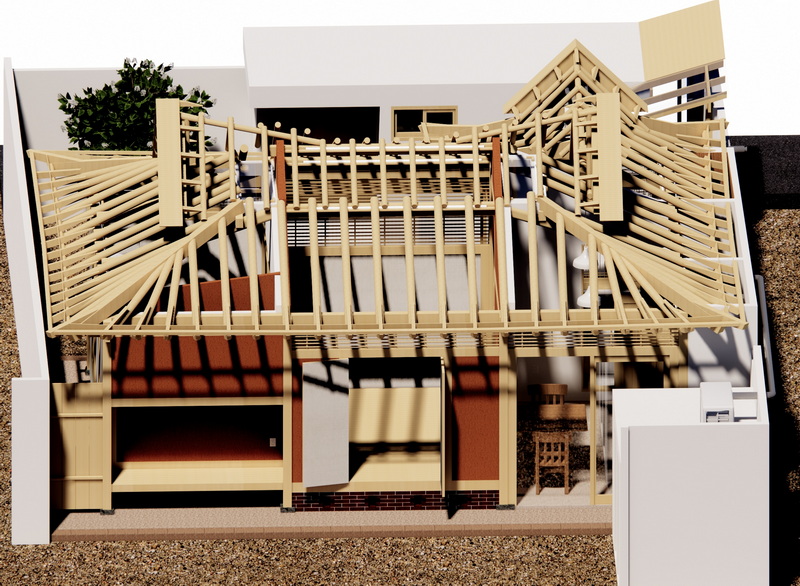

L-shaped structures do look prettier and more elaborate, but they also take much more effort to make than simple rectangle shapes, especially for roof structures. In the 1950s and 1960s, Gwangju and Honam hanok carpenters tried to reduce the effort and time required to make hanok for the enhancement of productivity and lowering prices by using simpler structures and hiding the rafters from the inside with plywood ceilings. In addition, they started to use raw timber and rough, unplaned wood from sawmills in the roofs, which was uncommon in the past. A little later, in the late 1960s and the 1970s, carpenters started to elaborate on home façades using large pillars and thicker rafters, though with much poorer quality wood and structuring (even worse than those of the 1950s and early 1960s) throughout the rest of the house, which were all hidden under plywood or wallpaper. Builders relied less on traditional timber framing joints and began relying on simple metal joints or nails. This quality deterioration of hanok structures was inevitable as the developers had to provide mass-produced hanok with the same style as rich people’s houses of the past at much cheaper prices.

Japanese-Style Cement Roof Tiles

During the colonial period, the Japanese brought many manufacturing facilities to Korea, including factories for their own building materials, and one of the materials they introduced was cement roof tiles. Cement roof tiles are less durable compared to ceramic roof tiles but easy and fast to make. After the Korean War, the need for houses grew everywhere, which increased the demand for roof tiles. Seoul’s mass-produced hanok continued to use traditional ceramic roof tiles that were made in small kilns temporarily installed near central Seoul until the 1950s.

Other regions usually used Japanese-style cement roof tiles for building hanok and other houses as they were easier to produce and install, and because they weighed less than traditional roof tiles, which also means that they required less wood for the structure. Another thing is that until that time, most residential homes had thatched roofs because only rich and high-ranking individuals could use ceramic roof tiles. Starting in the 1950s, as Korea’s hierarchical society collapsed after the Korean War, the demand for roof-tiled houses, which had been a distant dream for most, rose among the general public. Cement roof tiles were their only choice for mass-produced replicas of homes of the nobility as the supply for traditional roof tiles could not match demand in most regions of Korea, except Seoul and some touristic cities that got support from the government.

Embellishments

Usually, on each end of the roof there are triangular gables which usually have an ornamental face. During the Joseon Dynasty, these gabled faces were usually embellished with black traditional roof tiles, geometrical black brick patterns, or wooden planks. This custom also changed in the modern era to red brick, cement plaster, or glazed ceramic tiles. In Honam, tile work on the face is especially unique in design compared to other regions of Korea. Another distinctive ornamentation that had been used from the colonial period to the 1970s in Gwangju and Honam was the use of decorative nails on the gables. These were mostly in the shapes of flowers with delicate petals and were previously seen only on the houses of the upper class during the colonial period and premium houses during the mass-produced hanok era.

Conclusion

Through the architectural ingenuity and cost-efficient practices of the Gwangju and Honam home builders of the post-war period, many middle-class folks of the region were able to proudly live in homes replicating those once reserved for only the nobility.

Photographs by Kang Dong-su.

The Author

Kang Dong-su is a traditional Korean carpenter born in Gwangju in the year 1996. He started studying and archiving historical architecture in Gwangju at the age of 17. He is currently the representative of his company, Baemui, which researches and renovates homes and historical architecture in Gwangju and the Jeolla provinces. Instagram @baemui.naru