The Difference Between Book and Practice: A Conversation with Indie Bookshop Owner Shin Hyeon-chang

Written and photographed by Esther Kim.

Book and Practice (책과생활, Chaek-gwa Saenghwal) is an independent bookshop specializing in literature, philosophy, art, and design located on the second floor of a gray building on Jebong-ro. It sits above The Kitchen restaurant and next to the IMF fruit store, and is just a ten-minute walk east of Gate 4 of the gargantuan Asia Culture Center. Belying its nondescript exterior, inside is a cozy, curated space with the distinct smartness of a design bookshop. A turntable in the far corner plays jazz. The owner, Shin Hyeon-chang, is a former book editor from Seoul who opened the shop’s doors three years ago.

I caught Shin on a slow Tuesday afternoon. He brewed us some dark, pour-over coffee and sat down for a conversation about Korean book culture and publishing. I was accompanied by Han Jae-sub, a Gwangju local and art historian based at the ACC, who interpreted for us, and by Shin, who answered my flurry of questions. We spoke in a mixture of English, Korean, and “Konglish.”

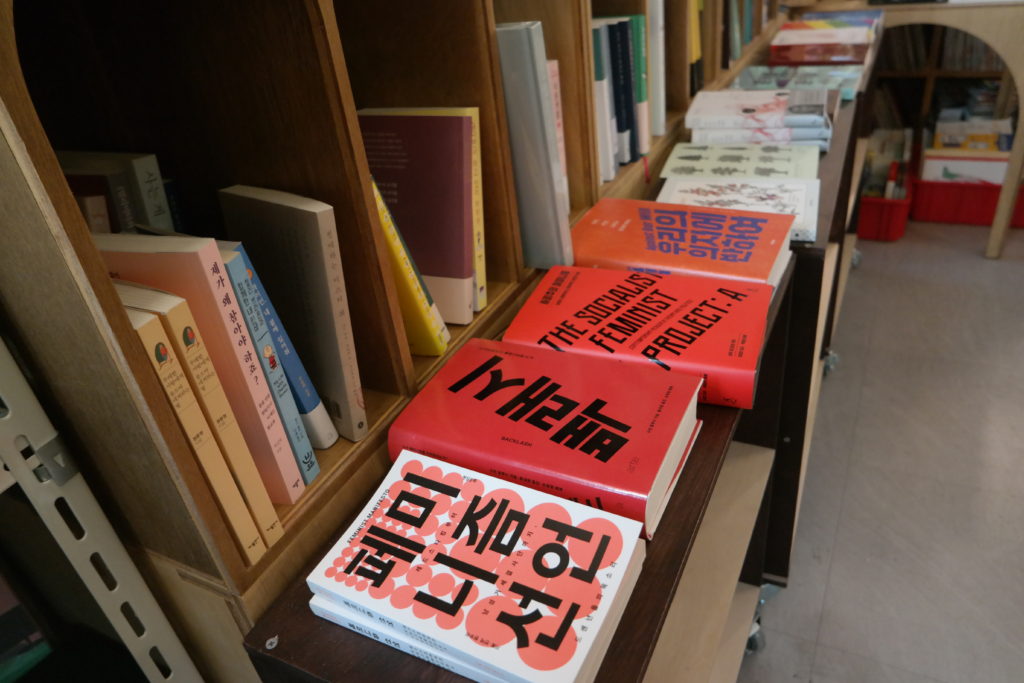

The wall closest to the entrance displayed books about the Gwangju Uprising (referred to as “5.18,” or oh-il-pal, in Korean). Next to the wall was a tall shelf of contemporary Korean novels by authors like Hwang Jung-eun, Choi Eun-young (to be published in 2021, Penguin Books), and Han Kang (winner of the Man Booker International Prize). Along the window was a display of art, design, and philosophy books, and the furthest wall of the bookshop held contemporary feminist books such as Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, Sister Outsider, and more in Korean translations.

Though Shin is a Seoul local, he’s lived in Gwangju for about six years. He worked in Seoul book publishing for over 20 years, and he also did a bit of freelance work, copyediting, magazine reporting, and even the odd ghost-writing stint. When I asked about his experiences traveling outside South Korea, he mentioned living in Berlin for a few months (trailing his girlfriend, an assistant to a famous installation artist). He was an editor at Hyunshil-munhwa, or HyunsilBook, a prestigious academic publishing house responsible for introducing heavyweight theoretical works by British, French, and German academics to South Korea in translation.

I asked Shin whether the strong regional and political differences within the peninsula are reflected in the publishing culture. (The Gyeongsang provinces are seen as wealthier and more conservative while the Jeolla provinces are considered working-class.) Was there a local Gwangju publishing scene? Not quite. Book culture here in South Korea is centered around the capital of Seoul or, more precisely, Paju – the famous book and publishing city located about one hour northwest of Seoul. It’s quite close to the DMZ (likely because the land was cheap.) Paju was first conceived in the 1980s, and the South Korean government asked the entire publishing industry to move, giving them some land and tax incentives, or something like that, so most of the country’s publishers moved. Today, over 100,000 people commute daily from Seoul to work in Paju. It’s a strange, quasi-urban industrial space – a meticulously planned, sprawling city out among the hills, packed with modern architectural buildings that house 250 companies covering every aspect of book publishing – from editing to printing and distribution.

While writers may live and write in Gwangju, almost everyone in the arts and culture industry (even if they are from outer provinces) will have gone to Seoul for graduate school or work. As the saying goes, “Body in Gwangju, Soul in Seoul.” Even amongst Gwangju locals, cultural consumption is oriented towards Seoul and copying the capital’s trends – there’s little homegrown book and literary culture – or perhaps not enough attention given to it. The only exception is books about the Gwangju 5.18 Uprising, which sell steadily here.

So why leave Seoul? Why Gwangju? It was something of a coincidence. After Seoul, Shin moved to Gwangju to establish the research arm of the new Asia Culture Center, conceived by President Roh Moo-hyun back in 2002 in an attempt to recast the city of Gwangju as a pan-Asian (international) arts and research hub. (It was like a form of reparations for the events of 5.18.) After Shin quit that gig, he contemplated his next steps. He considered moving back to Seoul to open a small press. But, he smiled, the rents are cheaper in Gwangju. “Somehow… I just stuck around,” Shin said. Because of that, there’s now a small and growing scene.

He opened the neighborhood bookshop in 2016. Back then there was a flowering of small independents that catered mainly to buyers in their 20s and 30s. For a city its size, Gwangju has a pretty large concentration of bookshops compared to other South Korean cities.

Of course, worldwide, the rise of online retailers and e-books has made it difficult for small and independent brick-and-mortar bookshops to survive. In the US, where I’m from, we have Amazon (not paying taxes while) undercutting publishers and bookshops, effectively laying waste to local book cultures. In South Korea, Shin explained, there are the huge retail brick-and-mortar bookshops like Kyobo, Aladin, and Yes24, along with online retailers like Ridi and Millie, a kind of Netflix for books. Needless to say, it’s not as easy to run an independent bookshop today, championing independent tastes, as it was yesterday.

To spark something local, Shin organized “The City’s Yawn” this year. It’s Gwangju’s first indie bookshop festival with a few Gwangju independent shop owners. Drinks and snacks are provided. Admission is ten won. To kick off the series, the poet Lee Byung-ryul launched his best-selling collection of travel essays Alone for the Alone (Honja-gah honja-eh-geh). Held on the second and fourth Saturday evening of the month at 7 p.m., the series ends on December 14, 2019.

As for the bookshop’s name, Chaek-gwa Saenghwal, chaek means “book” while saenghwal commonly translates as “life”; however, Shin calls it “practice,” as in “theory versus practice” (and gwa = “and”). I prefer this second translation. Book and Practice is a fitting name for the little bookshop, which was opened by an editor of heavily theoretical books out of aspirations to foster an intellectual community within the city – from the grassroots upwards, through everyday practice.

The Author

Esther Kim is a writer, literary translator, and former book publicist. She earned one MA in Korean literature at SOAS, University of London, and another in English literature at the University of Edinburgh. She is a native New Yorker, and her mother’s side is from Gwangju.